‘Try Everything to Find Them’: Districts Launch New Efforts to Get Chronically Absent 9th Graders Back in Class

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Janniya Benito, a 10th grader at Weaver High School in Hartford, Connecticut, describes herself as a “very hands-on learner.” Starting ninth grade remotely last year, she quickly fell behind and often skipped classes — especially English and math, where she felt the most lost.

“Being taught through the internet kind of sucked,” Benito said. “If I was in class, I wasn’t paying attention.”

It wasn’t until she returned to school in the spring that she saw her grades improve enough to pass.

The Hartford Public Schools, like other districts across the country, is now providing extra support for students like Benito after chronic absenteeism — defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year — spiked among ninth graders during 2020-21. While it’s clear the pandemic has set back learning for young children in the early grades, the transition to ninth grade has often fallen under the radar, even though experts call it a make-or-break year in terms of high school success.

Lacking many of the typical routines to help incoming freshmen adjust to the demands of high school and hindered by remote learning, many teens missed Zoom classes and turned up on lists of students considered most in need of support this fall. Now districts are using federal relief funds to hire staff and build new programs to target students that missed too much school.

Hartford — one of 15 districts participating in a state initiative to prevent further chronic absenteeism — has funded visits to students’ homes, hired staff members focused on student engagement and offered prizes for perfect attendance to help keep teens from backsliding.

When Connecticut officials examined monthly data, they saw a sharp increase in chronic absenteeism among ninth-graders learning remotely — close to 30 percent. Among Black and Hispanic students learning from home, the rates were nearly 40 percent.

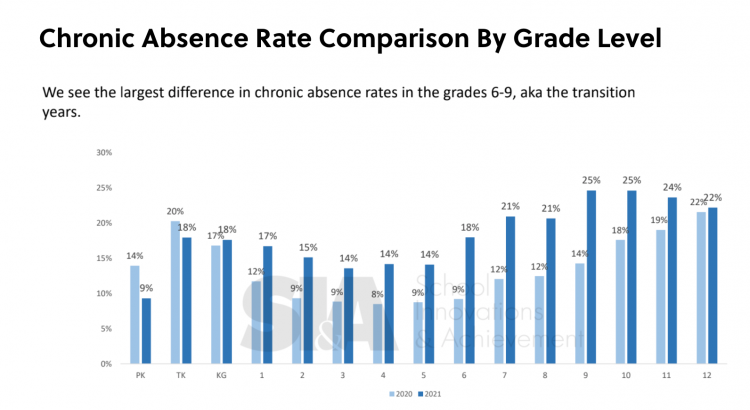

Across the country in California, the same pattern emerged in data examined by School Innovations and Achievement, a software company that works with districts to track and improve attendance. Chronic absenteeism rates hit 25 percent in ninth and 10th grade in the 2020-21 school year.

Experts note that even among those who have returned to in-person school, many teens still face pandemic-related challenges that impact attendance.

“We know that many high school students are continuing to struggle with trauma, grief, economic and housing instability, academic disengagement, [a] lack of social connections, or staying in school while holding a job or caring for family members,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, a research and advocacy organization, “High schools can make a real difference despite these challenges.”

‘We went out to their homes’

Research shows that if students are not on track in ninth grade, their chances of graduating drop, and that consistent attendance ranks nearly as high as good grades in determining whether freshmen stay on track through high school. Districts often use the spring and summer months to smooth the transition from middle school into ninth grade with activities such as campus tours, summer bridge programs and new student orientation. But in 2020, and again this year, many of those efforts were cancelled or replaced with virtual sessions. Students often missed opportunities to meet new friends and teachers.

Administrators looked for new ways to strengthen those connections. In north Georgia, Murray County High School Principal Gina Linder assigned every incoming ninth-grader a counselor and a social worker. Even though her school started the fall of 2020 in person, she said she always loses some students as they “roll up” to ninth grade, and she feared it would only worsen because of the pandemic.

“We went out to their homes. We looked for the kids on social media,” she said. “We went to their job sites and said, ‘We miss you at school and we’ve got programs that allow you to work and still be in school.’”

Absenteeism further increased when students had to quarantine because it wasn’t always clear if and when they were supposed to log on to classes. At one point, about a third of the school’s 1,200 students were out and some had to quarantine six times, Linder said. When cases spiked, parents kept their children at home.

Then the district shifted to remote learning over the winter months when transmission rates increased. Students had Chromebooks and hotspots, but that didn’t guarantee they were keeping up with school.

“We were pushing work out to them, but these kids needed the same learning expectations at home” that they had in school, Linder said. They were more likely to attend virtual classes if they had to follow the same “bell schedule” at home. Even if teachers recorded their lessons, students “were not going to watch seven videos at 8 at night,” she said.

This fall, the district is using $255,000 in relief funds from the American Rescue Plan to hire extra bilingual staff members at each school to focus exclusively on attendance.

In the northwest corner of Arkansas, the Gravette School District is using relief funds to support a new director of academic success.

Last year, if ninth-graders learning remotely skipped classes, the district urged parents to switch to in-person instruction. This year, Kelly Hankins, who took the new position, is relying on data and her personal relationships with many families to nudge students back toward consistent attendance. Working with School Innovations and Achievement in California, she’ll be able to identify patterns, such as whether students are more likely to miss morning or afternoon classes. When students quarantine, she contacts them daily.

“Hopefully, that will keep them motivated,” she said. “It’s hard on those at-risk kids to be in a routine, and [then] all of a sudden, they’re not.”

The return to school this fall hasn’t necessarily solved the problem. Districts like Oakland Unified in California are still seeing at least 20 percent of ninth graders chronically absent. And students in quarantine are missing instruction because many states and districts stopped offering remote learning. According to a recent review by the Center on Reinventing Public Education, only 12 states have provided guidance to districts on how to track attendance for students in quarantine.

In Hartford, when leaders surveyed every chronically absent student, they found that teens were often helping younger siblings with remote learning or doing household chores. The return to in-person learning has removed many of those distractions.

“When a student is in school, they can’t be asked to do anything family-related,” said Isaiah Jacobs, a student engagement specialist at Weaver High and a graduate of the school.

Melvin Viard, a 10th grader at Weaver, said he had trouble understanding some of his assignments last year and couldn’t stay focused during remote classes. He either fell asleep or got up and walked around the house during lessons. But now he said his grades are good and he’s on the football team. “It was way better for me in person,” he said.

The state’s data showed that ninth-graders who attended in person had fewer absences than those learning remotely — about 13 percent compared with the 30 percent for those at home. But Jacobs said even among those with a hybrid schedule, students sometimes decided to come to school “based on how they woke up in the morning.”

Some students started working during the pandemic and need to continue, so the district has added evening school — with dinner included — to allow them to make up credits. And during the day, Weaver students can get more individual attention to help them with academic and personal challenges through the school’s new success center, an expansion of a program launched at Hartford Public High School before the pandemic.

‘No magic solution’

After the initial survey, staff members followed up with interviews to learn more.

Corinne Clark Barney, the district’s executive director of school leadership, said among high school students, a common barrier to attending school in person was the fear of COVID.

That fear hasn’t necessarily gone away. Milly Arciniegas, executive director of Hartford Parent University, a nonprofit advocacy group, said some parents still worry that the full return to school was too abrupt.

She wants the district to offer a virtual option and to prioritize free, high-speed internet access.

The district, meanwhile, is hoping to entice teens to come to school through incentives like “dress-down” days, attendance competitions between grade levels and raffle prizes like AirPods and big-screen TVs. Weaver added it’s own incentive for September — a $100 Foot Locker gift card — and saw 140 students earn perfect attendance that month.

Jacobs said the school plans to add smaller goals for students to hit as well, such as two weeks of perfect attendance. “A lot of students need instant gratification,” he said.

In Murray County, Linder found last year that rewarding students with a distance learning Friday was another effective way to increase attendance. Those who were still struggling had to come to school.

“There’s no magic solution,” she said. “The biggest thing I’ve told my whole faculty is we have to know where our kids are, especially during these times. Try everything to find them and hold them accountable.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)