New Data Links Remote Learning in Connecticut to Chronic Absenteeism at Key Transitions; 30% of Ninth Graders Missed At Least a Tenth of Last School Year

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

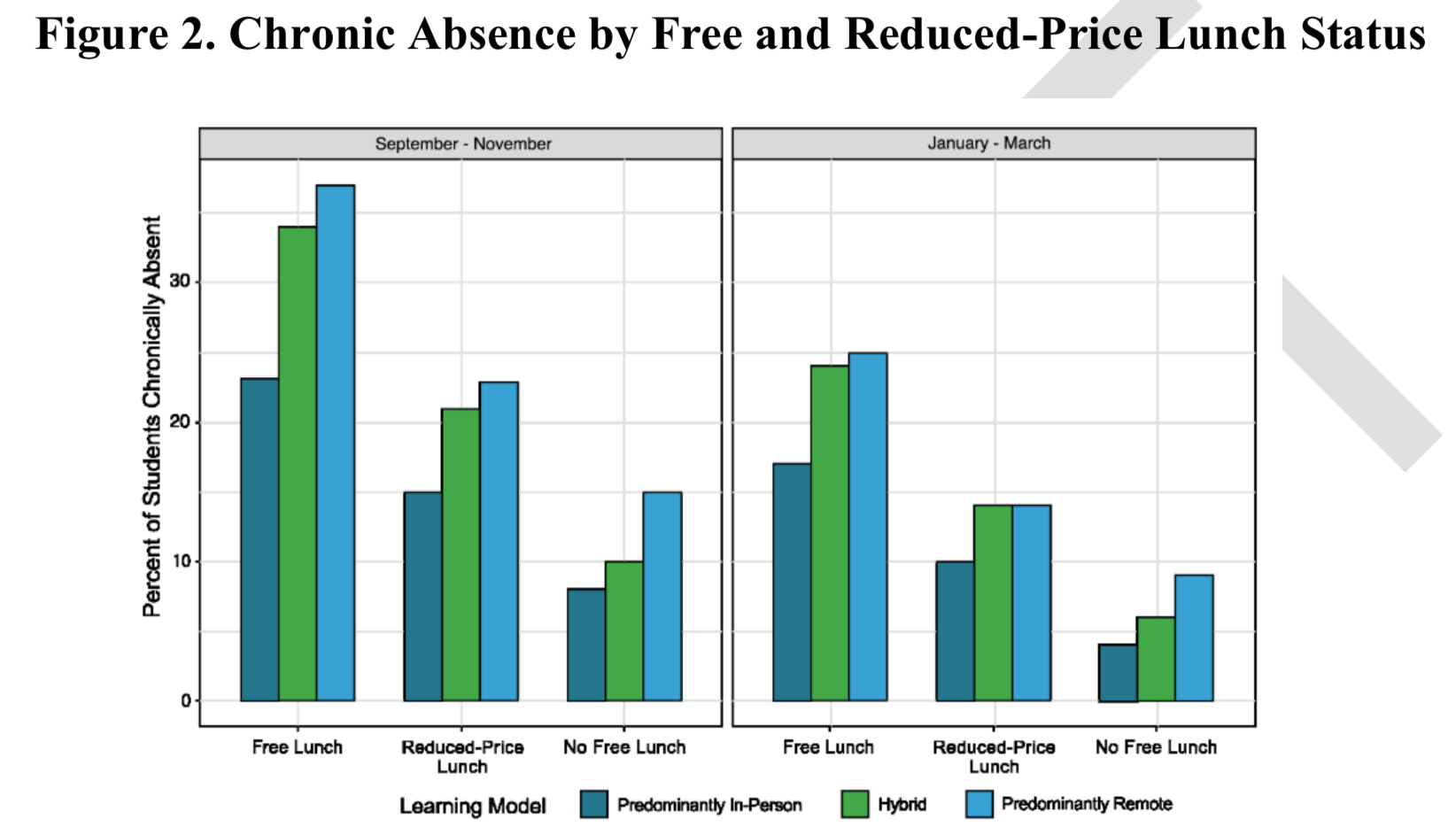

Students learning remotely missed the most days of school this year, according to new data from Connecticut. And students who were chronically absent in the fall were far more likely to keep missing school during the winter months.

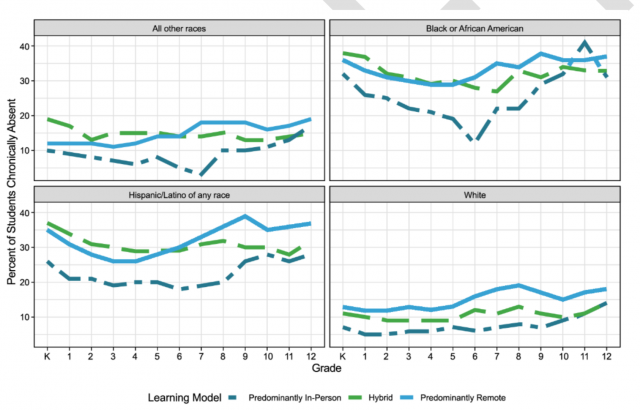

The analysis, from the Connecticut Department of Education and advocacy group Attendance Works, shows that rates of chronic absence — defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year — were highest among students in low-income communities, English learners and students with disabilities. And the rates of poor attendance among Black and Hispanic students were two to three times higher than those of their white peers.

“It’s very likely that the trends they are seeing are similar in other states,” said Hedy Chang, the director of Attendance Works. Whether other states see those trends in their data, however, depends on how they decided to count attendance for students learning at home.

Connecticut, which implemented a new process for tracking absenteeism across in-person, hybrid and remote settings, required students to attend school for at least half a day to be marked present. If they were at home, they were responsible for participating in at least half of the virtual class time and the other offline work scheduled for that day. New Jersey adopted the same definition, but many states left the decision up to local districts or allowed a mix of criteria, sometimes nothing more than daily check-in call or a simple log-into a remote class. As of January, 19 states weren’t even requiring districts to take attendance, according to the report.

As officials debate whether they’ll allow some remote learning this fall, the Connecticut data shows chronic absenteeism among remote learners was at its worst in kindergarten and ninth grade — key transition points when in-person learning for students might be especially critical. The findings, Chang said, point to the need for leaders to track daily attendance, set consistent definitions for when a student is counted absent and build stronger connections with families so educators can intervene if a student misses too many days of school. With leaders beginning to craft plans for using federal relief funds, the report also highlights the ways Connecticut is spending last year’s federal money to target districts serving high-need students.

The state was among the first to ensure all students had devices and an internet connection, when U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona was still commissioner. But stories of families’ remote school experiences have shown that digital access doesn’t always translate into real learning.

“You’re at home. You have three kids all online and there’s one room,” Chang said. “That’s not a solution.”

‘Re-establishing relationships’

The Connecticut report adds to the findings of a recent examination of attendance trends from FutureEd, a think tank at Georgetown University. Summarizing data from five unnamed districts serving roughly 450,000 students, the report concluded that severe absenteeism has worsened during the pandemic. In one district, 7 percent of students missed as much as half of the school year, compared to none who were absent that often before school closures.

The report draws on data from EveryDay Labs, a company that works with districts to improve attendance. The company noticed an increase in perfect attendance rates across the five districts, which points to the lower bar that some states and districts set for students.

Phyllis Jordan, editorial director at FutureEd and author of the report, said it’s clear that students missing half the school year need a lot of support. But if a student who just logs in briefly is counted present, that “makes it hard to figure out who’s in trouble,” she said.

To improve attendance among those most at risk of disconnecting from school, Connecticut spent almost $11 million from last year’s relief packages to create the Learner Engagement and Attendance Program — or LEAP — which includes home visits, summer learning programs, housing assistance and mental health support in 15 districts. State leaders also meet weekly with district representatives to discuss attendance issues among homeless students, English learners and other groups of students with higher than average absenteeism.

“We know the reasons for chronic absence are as many as there are kids,” said John Frassinelli, director of the department’s division of school health, nutrition, family services and adult education. “It’s really about establishing and re-establishing relationships with families.”

The East Haven Public Schools, south of Hartford, isn’t part of LEAP, but educators still routinely tracked attendance data to identify which students needed additional support. And when the district held standardized testing, Chris Brown, principal of Tuttle School, invited remote students to sit at desks outside the building to take the assessment. The practice spread to other schools.

“It was how we could draw parents in and get them on campus just to talk to them a little bit,” said Superintendent Erica Forti.

In a FutureEd webinar Tuesday, Charlene Russell-Tucker, Connecticut’s acting education commissioner , discussed the importance of working with health, child welfare and other state agencies when addressing attendance challenges.

“We all have responsibility for the same group of children, so why not collaborate and share resources?” she asked, adding that this approach has been especially helpful when families are hard to reach. “Somebody knows where they are, so it’s really important for us to connect.”

‘All over the map’

Connecticut began capturing attendance for students learning in-person, in a hybrid model and fully remote and then reported it monthly — instead of at the end of the school year, which is more common. The change allowed district officials to respond more quickly when they saw patterns of poor attendance or participation in remote learning.

Chang added that if states or districts have outdated software programs that don’t allow them to track and report attendance for both in-person and remote students, they should consider using relief funds for an upgrade.

Connecticut’s process allowed educators to notice which students struggled the most with attendance and identify trends they might not have seen otherwise.

While districts nationally saw sharp declines in kindergarten enrollment, for example, the Connecticut data shows that those who did enroll still missed a lot of school. The data suggests “kids are going to be all over the map of where they are with learning” this fall, Chang said.

In ninth grade, there was a spike in chronic absence rates to almost 30 percent for students learning remotely, which Chang said likely points to the challenges students faced starting high school without in-person interaction with teachers and peers.

“All the things we typically would have done to ensure a smooth transition to high school did not happen for these kids,” Chang said. “If you start missing a lot of ninth grade and getting D’s and F’s, you are not on track for graduation.”

Another trend at the high school level was more positive. In both fall and winter, there was little difference in chronic absence rates for students learning in person and in hybrid models.

To Chang, that suggests the flexibility of a hybrid schedule could benefit older students, especially those who need to work. “There are some things that we were forced to do by COVID that we might not want to give up,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)