There’s Lots at Stake for Districts & Kids When Underenrolled Schools Stay Open

Aldeman: $190 billion in ESSER funds & 'hold harmless' rules have allowed districts to delay difficult school closure conversations. That’s a mistake.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

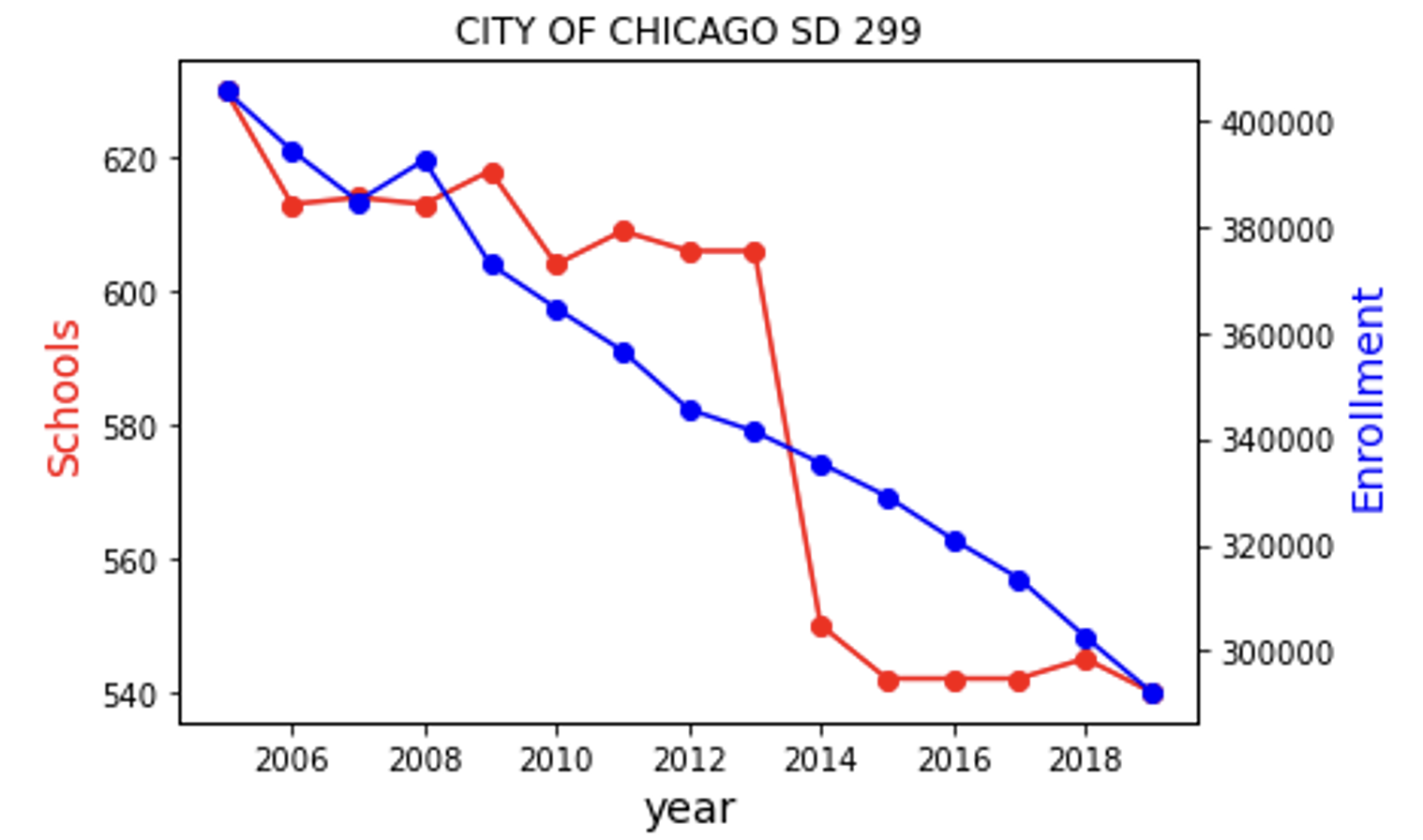

At a research conference in late March, Princeton economist Richard DiSalvo presented some startling graphs comparing student enrollments against the number of schools serving those students.

By contrasting these two trends, DiSalvo could measure whether and how much districts suffer from what he called adjustment inertia. In other words, do districts open new schools as student enrollments rise, and do they close schools as enrollment falls?

His findings are not entirely surprising: On average, districts have an easier time growing when demand is rising than they do shrinking when enrollments fall. It’s also comparatively easier for districts to adjust staffing levels up or down than it is to adjust their physical footprint in the form of school buildings.

Some districts manage this process better than others. Consider DiSalvo’s graph on Chicago. Student enrollments (in blue) were declining over time. But the district delayed its decisions to close schools, eventually resulting in a big wave of school closures (in red).

That school closure in 2013 made national news. Under then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Chicago shuttered 49 elementary schools, the largest school closure in the country’s history. It uprooted tens of thousands of students and teachers, harmed both the displaced students and the schools that eventually received them, and set off a wave of political debates that are still being felt.

However, DiSalvo’s data shows that such events are not inevitable. For example, Milwaukee and Kansas City stood out as districts with relatively little adjustment inertia. As enrollments dropped, they gradually scaled down the number of schools.

Closing a school, in general, is bad for students, but it’s worse when districts have to shutter many at once. In Philadelphia, for example, researchers found that achievement among both displaced students and those at the receiving school fell more as the number of displaced students rose. In other words, the sheer size of the closure made the fallout worse.

Besides being strategic on the timing of closures, districts can also take steps to mitigate the harm done to students. As EdNavigator’s Tim Daly wrote earlier this year, when districts put supports for displaced students in place, they can fare better academically than they did in their former schools.

DiSalvo’s data ends in the fall of 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked further havoc on public school enrollments across the country. As of the latest data, public schools were serving 1.3 million fewer students than they did pre-pandemic. Thanks to declining birth rates and years of reduced immigration, enrollments are projected to decline by another 4.4% nationally by the end of this decade.

Estimates are that public school enrollments will fall in 42 states, topped by West Virginia, with an estimated decline of 20%. In numeric terms, the biggest losers are likely to be New York and California, with forecasted declines of 149,000 and 530,000 fewer students, respectively.

That translates into a lot of districts with a lot of underenrolled schools. The infusion of $190 billion in federal ESSER funds, not to mention state “hold harmless” provisions, has allowed districts to hold off difficult school closure conversations.

But that’s a mistake. The surge in budgets over the last few years represents a lost opportunity for districts to right-size their physical footprints. It would have been wise to use the federal funds to soften the blows and create supports for displaced students while the money was there. By putting off those decisions, districts will likely have to close many more schools in the years to come, after the one-time money runs out.

The financial aspect is obvious for green-eyeshade types like me. If a school serves fewer students, the cost of providing the same services will rise on a per-capita basis. As a result, underenrolled schools start to look like costly outliers. (For anyone wanting to take a look at their district, I’d recommend checking out the School Spending & Outcomes Snapshot database, created by the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University and hosted by the National Comprehensive Center.)

But the arguments in favor of closing underenrolled schools are not merely financial. Kids at those schools miss out on the full complement of staffing or programming that they’d otherwise receive. Districts can’t continue to offer music, art, electives, counselors, extracurriculars or other specialists at the same levels when they spread their resources too thin across too many buildings.

Smaller schools are neither entirely good or all bad. But, because districts’ revenues are tied to how many students they serve, they have to make choices about how to allocate resources across schools. Budgeting is a trade-off. When enrollments decline, the district can spread its staff across a large number of buildings and let each school operate with a skeleton crew, or it can close some schools so more students can attend schools that offer a full suite of services.

Of all the decisions school district leaders must make, whether or not to close a school can be particularly fraught. But deciding not to shutter underenrolled schools is also a policy choice. It means that students will get fewer services in the short term, and it raises the chance of a potentially harmful massive school closure down the road. That risk is particularly high right now.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)