Analysis: State Laws Leave School Districts Unprepared for Looming Fiscal Cliff

As federal relief funds expire, one expert said, ‘students will suffer if districts wait too long to rein in their spending.’

By Linda Jacobson | July 20, 2023For the past three years, districts have received more federal money than ever — $190 billion — to hire staff, dole out hefty bonuses and address the learning loss and mental health problems fueled by the pandemic.

The expiration of these funds in about 14 months could be the biggest jolt to school finances that districts have ever faced. But an analysis by The 74 has found that the majority of states lack laws to protect districts from a fiscal emergency like this one — a fact that could leave school systems unprepared for the upheaval to come.

“Deficits will creep up quickly and really destabilize a district,” said Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab. “In the end, the students will suffer if districts wait too long to rein in their spending.”

School systems currently face compound pressures. Declining enrollment means less state funding, and they’re paying higher prices for staff because of a tight labor market and more for supplies because of inflation. To better withstand the strain, experts like Roza advise districts to estimate their revenues and spending a few years in advance, taking into account enrollment trends, taxes and the potential for an economic downturn.

But only six states have such requirements. Experts also recommend setting aside money for fiscal emergencies, but just 10 states mandate the practice.

Most states view district budgets as a local matter. Officials say they can offer little more than advice as the education system heads for what Roza calls a “wild ride.”

“For these next few years, … state monitoring of finances is an absolute must,” she said. Relief funds have “distorted district finances. Many are overcommitting at a time when they should be downsizing.”

She pointed to the San Diego school district as an example. In June, the board approved a 15% raise for teachers to avoid a strike, at a cost of $517 million. But projections show a nearly $129 million budget shortfall by the 2024-25 school year.

The end of relief funds could also collide with tax cuts in some states, further impacting what programs, like tutoring and summer school, districts will be able to sustain. In addition, Congress’s recent deal to prevent the government from hitting a debt ceiling and defaulting on its financial obligations could affect how districts wean themselves off pandemic money.

The deal between conservative Republicans and the White House wiped out the chance for an increase in federal K-12 spending next year — money that could have cushioned the blow once COVID money dries up. Now the House is proposing a 15% cut in the education budget.

“If I’m a state budget director, the debt limit deal tells me I’m on my own to try to soften the cliff landing with added revenue,” said Jonathan Travers, managing partner at Education Resource Strategies, a nonprofit that advises districts on financial matters. “I might have been holding out hope for help from Title I, but that seems gone now.”

Planning for Fiscal Emergencies: Three Maps

‘Grounded in the truth’

Districts have been down this road before.

The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed in the wake of the Great Recession, was at the time the federal government’s largest one-time investment in schools, providing districts close to $71 billion in extra funding. When those funds ran out, however, many districts were unprepared: They cut jobs, imposed hiring freezes and increased class sizes.

A 2012 report from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of the Inspector General examined spending decisions in 22 districts, including the Wichita Public Schools in Kansas.

Susan Willis, the district’s payroll director at the time, remembers a “pretty ugly” seven-to-eight year period with no raises for teachers. The district eliminated its grants department and several facilities and professional development positions. Enrollment was growing, so leaders “couldn’t be looking into the classroom for reductions,” said Willis, now the district’s chief financial officer.

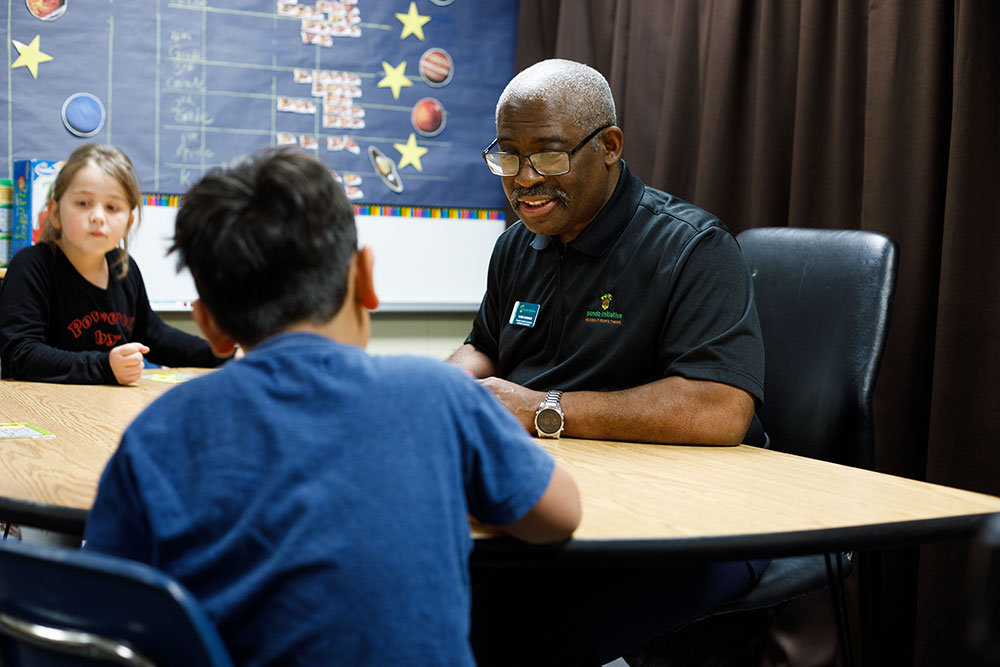

A decade later, Wichita’s enrollment is declining, and as pandemic aid expires, leaders are looking to eliminate positions they could have cut earlier, but didn’t — particularly at the elementary level. The challenge, Willis said, is how to offer salaries high enough to compete against suburban districts while continuing to fund counseling and mentoring programs that she thinks have lifted graduation rates back above 80%.

The 2012 report said that a funding cliff doesn’t mean that districts didn’t make good use of temporary funds or that the relief funds weren’t the “right call.” Leaders just need to be “grounded in the truth, no matter how brutal,” Travers said.

Budget reserves

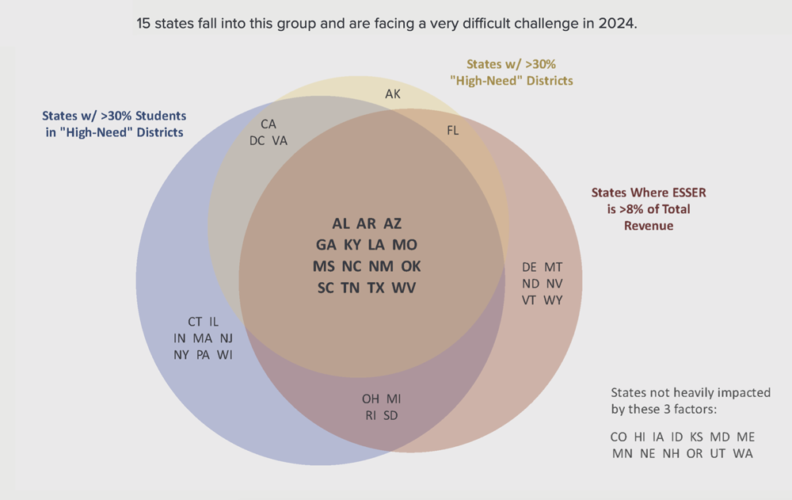

Whether the fiscal cliff turns out to be a gradual slope or a precipitous drop could hinge on how much federal money a district received. A March report from Education Resource Strategies identified 15 states where the expiration of those funds will hit harder because they received more federal aid and have a lot of districts with high poverty rates.

Travers said it will be easier to identify which districts “have the potential for a painful landing” later this summer when auditors review districts’ finances from the past year. It’s “critical,” he added, that states keep a close watch on districts where relief funds total more than a quarter of their annual budget. The more money districts received, the harder it could be to reduce spending once the funds disappear. That could include some of the nation’s largest districts, including New York City and Houston and those with high-poverty levels like Detroit and Philadelphia.

To prepare for lean years, Ohio, for example, requires districts to estimate their budgets five years in advance. Washington mandates four years. But in some cases, school finance officials’ desire to plan ahead conflicts with budget timelines.

“We can’t forecast because we never know what our state aid is going to be every year,” said Susan Young, executive director of the New Jersey Association of School Business Officials.

The state doesn’t require districts to put aside funds for emergencies. But those that choose to could find themselves brushing up against a state cap that limits reserve funds to 2% of their budget. Young’s organization would like lawmakers to raise that limit, especially as relief funds expire. Some have already made drastic cuts and are asking voters to raise property taxes.

Reserves can help school systems with a temporary shortfall, but can’t do much for a financially strapped district that has ignored enrollment loss or failed to issue layoff notices in time for the next school year. Like COVID aid, reserves eventually dry up.

“There are no reserves that are going to buy you a whole school year,” said Michael Fine, CEO of California’s Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, which was created by a state law in 1991.

The California law also created an early warning system in which county education agencies must sign off on district budgets and, when a district is headed for insolvency, can wrest authority from a superintendent and school board.

Sixteen states have similar processes, some more extensive than others. Texas, for example, grades districts on whether they pay their bills on time and post financial information. The Kentucky state board monitors any district that adopts a budget with less than 2% of its revenues set aside for reserves.

In California, 13 districts are now in serious financial trouble. Ten may not be able to meet their financial obligations in the next couple years, and three, Fine said, “are running out of cash.”

Given the pandemic windfall, he’s surprised any hit that point. But with the state’s gloomy financial outlook, he expects more to find themselves on the list.

“The news probably only gets worse for 2024-25, not better,” he said.

In southern California’s San Bernardino County, where 33 districts are spread over 20,000 square miles, Thomas Cassida, director of business advisory services, expects the majority of them — 28 — to have a budget deficit in 2024-25 or the year after.

They still have time to scale back. For example, some have spent relief funds to open health centers, but might have to cut positions for the counselors and other mental health professionals hired to run them.

He’s most worried about districts that were in bad financial shape before the pandemic. When the relief funds are gone, they could find themselves in the same place.

“Every county has at least one district that is a problem child,” he said.

In Ventura County, it was the Ojai Unified School District, where Fine said leaders ignored multiple warnings about the need to cut roughly $3 million. About 30 minutes from the coast, Ojai is known for boutique hotels and wellness retreats. But tensions ran high at a Feb. 21 school board meeting where Fine showed up unannounced to deliver a sobering message.

“You are beyond financial trouble, and you are in fiscal distress,” he told the board and superintendent. “If you were a private business, you would now be out of business.”

Less than a month later, the board cut more than 30 positions and fired the superintendent.

“Parents were extremely frustrated and upset by the news of the budget deficit,” said Sherrill Knox, an Ojai native and former assistant superintendent who took over as the district’s new chief this month. The crisis, she added, was “nestled in an ongoing, long-term issue of the need to downsize our district.”

While Ojai was an extreme case, Fine said declining enrollment is affecting districts statewide, and smaller school systems can quickly downgrade from financial difficulty to fiscal distress. He largely blames “inadequately trained” school board members.

“In most cases, it’s stupid governance and leadership that got them into this spot,” he said, “and it will be good governance that gets them out.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter