The ‘Middle Skills’ Gap: Half of America’s Jobs Require More Than High School Diplomas but Less Than 4-Year Degrees. So Why Are They Under So Many Students’ Radars?

Mitchell Block is a lineman for two counties. He drives the main roads tending to the power lines along the western lakeside of Michigan.

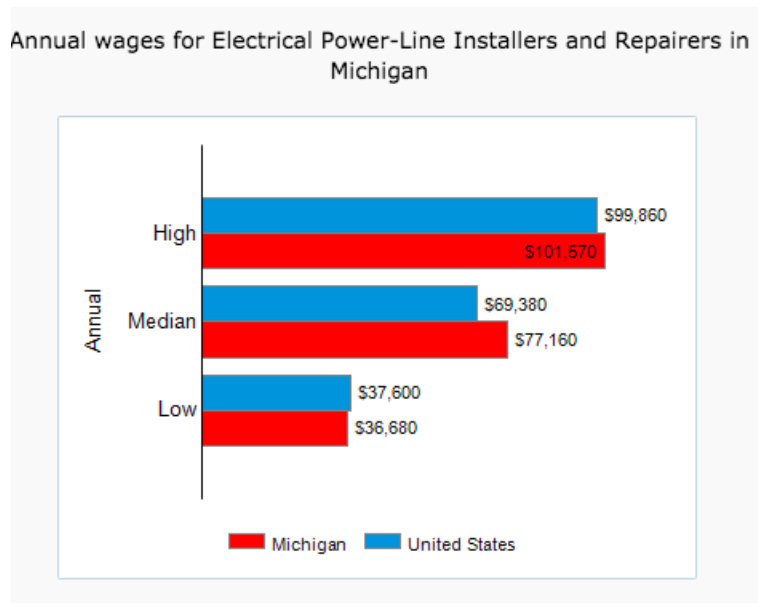

It’s more accurate to say Block is an apprentice lineman, a few months from earning his journeyman’s card after four years of training. He can look forward to a union-protected salary, a retirement at an average age of late 50s, and yearly earnings north of $100,000 after overtime, according to an energy company official.

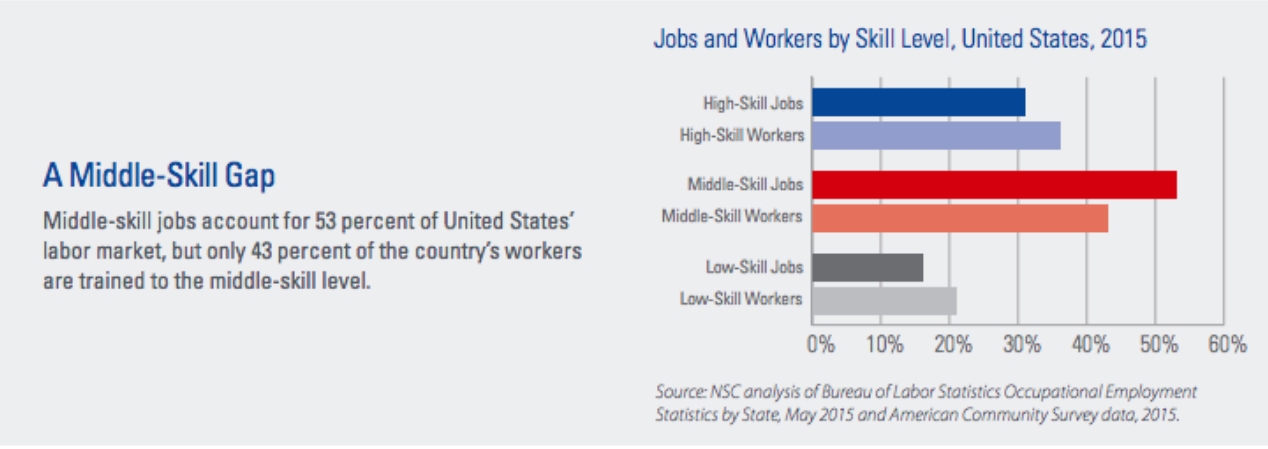

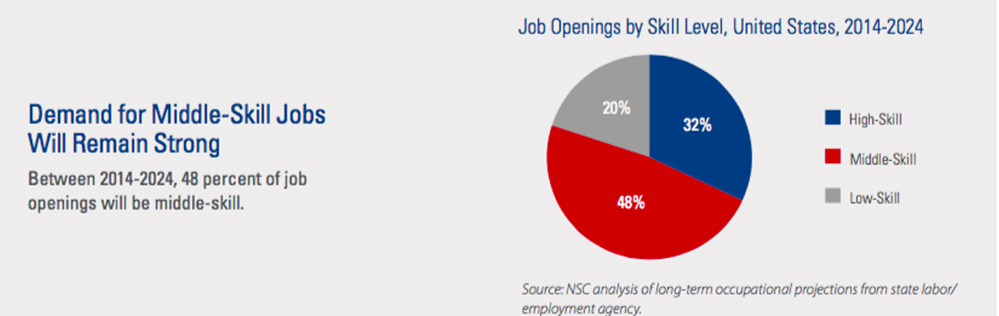

Block is a member of the so-called middle-skills workforce, which comprises the lion’s share of the American labor market. Despite making up a critical share of the economy, middle-skills jobs — those that require more education or training than a high school diploma but less than a four-year college degree — are only now slowly beginning to gain the attention of those focused on the K-12 education pipeline meant to prepare American children to meet the country’s labor needs.

“I don’t plan on changing jobs again,” Block said, shortly after returning to ground in his hydraulic bucket. For 18 years, he helped plan the routes of new power lines for Consumers Energy, the local power company. During most of that time, he said, he dreamed of being up on those lines.

“Something inside me wanted to do this job,” said Block, 36. “You do a job that, let’s face it, not everybody in the world can do. And when someone says, ‘What about being up there in storms and the rain?’ Well, that’s when you’re really helping people.”

Block enrolled in a 13-week line workers program at Lansing Community College, one of two in the state that offered the specialized training required for the job. Through an initiative to develop more students qualified to work on Michigan electric lines, his community college performance earned him a spot at Consumers Energy’s pole-climbing boot camp for the company’s future line workers. The collaboration between state higher education, business, and local government created a rapid career path change for Block and produced more than 100 line workers amid statewide shortages.

Source: CareerOneStop, U.S. Department of Labor

Getting the word out about middle-skills jobs

Success stories that involve parlaying a vocational certificate into middle-class security need more attention, workforce groups say.

The flow of students into colleges has slowed — between 2011 and 2017, undergraduate and graduate student enrollment in degree-granting institutions fell by 1.7 million students, or about 9 percent. But both the perceived and real value of a bachelor’s degree as a pass-through to high-paying professional success seems unlikely to diminish in the foreseeable future.

A continued emphasis on postsecondary degrees and white- and gold-collar jobs puts even more pressure on educators and employers to answer the unmet demand for middle-skills workers. So, advocates say, students must be exposed to these less-considered but greatly needed careers — and they must be taught that earning a four-year degree is not the only path to success.

It may be easy to forget that college as a prerequisite is part of a fairly recent paradigm shift. In the 1970s, before computers began to radically reshape the economy, just 20 percent of jobs in America required education or training beyond high school.

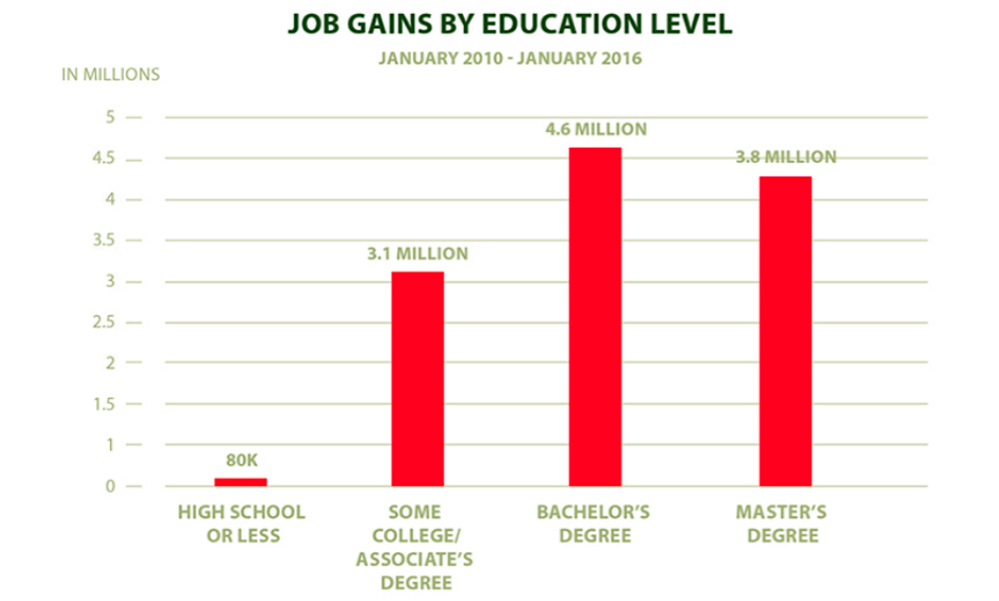

Today, that figure stands at more than 60 percent. Since the Great Recession, 11.5 million of 11.6 million new jobs demanded postsecondary academics or training. In calculating the value of a four-year degree, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that from 1970 to 2013, degree holders earned 56 percent more than those who had only a high school diploma.

To better ready students for college-level work, school systems have implemented higher standards, instruction that requires deeper student engagement, and harder tests. But groups that help students transition to postgraduate life say a conveyor-belt preparation model has contributed to students enrolling in college unprepared or uninterested, which has resulted in large gaps in completion rates between high- and low-income students, crippling student loan debt, and wide inequities by race and income on markers like employment and incarceration.

In collaboration with educators and business leaders, advocates are creating programs across the country that expose students during the school day or after school to middle-skills professions. Ranging widely across sectors like health care and information technology, law enforcement and the trades, about half the country’s jobs fall into this category. But elevating middle-skills work was not among the reform priorities of No Child Left Behind, nor its K-12 successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act, during the respective Bush and Obama administrations.

“We have young people who are increasingly disconnected, we have jobs and jobs and jobs that are unfilled, so we’ve got to build the bridges to make sure these kids get their jobs,” said Cate Swinburn, president of YouthForce NOLA, a New Orleans nonprofit that provides job exposure and training across local industries for students beginning in ninth grade. “There have never been bridges for our low-income and black students to good jobs.”

Breaking through student assumptions

The benefits of college can overshadow its risks. Enrollment has risen by about 50 percent since the 1980s (slowing after 2010), but only about one-third of Americans have four-year degrees. Completion is correlated with income: the Pell Institute, which reports on inequality in higher education, found that 58 percent of students from families in the top quartile of income earned bachelor’s by the age of 24, while the same was true for just 11 percent from the lowest-earning quartile.

Low success rates among less affluent students along with rising costs, declining wealth accumulation for graduates, and the lack of good job and wage prospects for many majors all fueled the move to diversify students’ post-high school options.

“The return on investment for a bachelor’s and advanced degree is very high, much higher than the stock market or real estate,” said Jeff Strohl, director of research at the Center on Education and the Workforce.

“But dropouts get all the downsides and none of the benefits of the system,” he said. “Your chances of accessing the middle class — the idea of education as the great equalizer — are taken away.”

Career and technical education in high school and community college has increasingly targeted middle-skills occupations, which may require more training and where employers have not been able to fill shortages — particularly in growing fields like health care and cybersecurity.

Missy Sparks, an executive with Ochsner Health System, one of Louisiana’s largest employers, says working with YouthForce NOLA gives the company the chance to break through students’ assumptions about the kinds of jobs they can get.

“I need to get to kids sooner, as they’re thinking through career pathways,” Sparks said. She listed shortage positions ranging from physician’s assistant to pharmacist to medical lab technologist, along with opportunities in IT, communications, and artificial intelligence. “I want to give them exposure to a range of jobs where I need help.”

YouthForce NOLA sponsors year-round and summerlong internships at Ochsner that allow students to experience as much of the “health environment” as possible, Sparks said. They watch operations, learn to make sutures, and attend presentations where professionals describe the education and responsibilities their jobs require.

The smorgasbord approach makes sense to Shaun Dougherty, a professor at Vanderbilt University who believes vocational programs should avoid narrowing options for students too early.

“What I’ve done over the last 10 years doesn’t align with what I wanted when I was 16,” said Dougherty, who studies career and technical education. “We should probably do things in high school that make [students] feel they have agency about what they want to do as adults but doesn’t mean they’re signing up for that for the next 10 years.”

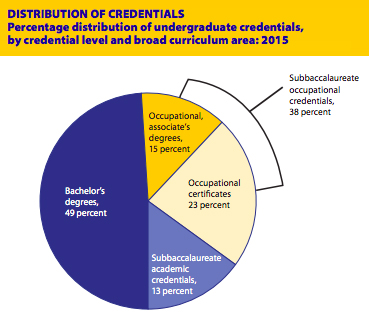

Even before college enrollment began to dip, educational and career pathways that culminated in certificates and associate’s degrees grew more quickly than four-year degrees between 2004-05 and 2014-15.

The electrical line worker program in Michigan, supported by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Consumers Energy in response to the company’s shortage of qualified workers, targeted areas where the power company had been successful in recruiting workers in the past. Students who excelled in the community college program pipelined into the power company to begin an apprenticeship. The arrangement yielded 124 new line workers over two and a half years who could look forward to a steep return upon completing their training, according to one of the initiative’s architects.

“They start at $28 an hour and move up rapidly,” said Sharon Miller, who oversees workforce issues for Consumers Energy, describing an income annualized at around $50,000. “I believe most are at $40 to $45 an hour. But overtime is prevalent, and that’s how they can get to six figures.” Miller said line workers retire in their mid- to late-50s.

The line workers face a somewhat lower ceiling on future earnings than college graduates with lucrative majors. The job is also relatively dangerous, with about the same incidence of fatalities as police officers, but wages compare favorably with those of most graduates of four-year colleges.

What ‘schools don’t teach and labor markets don’t supply’

Despite an availability of middle-skills jobs in many occupations, challenges persist.

Employers and others have attributed shortages in some occupations to a “skills gap” arising from insufficient training, particularly where advances in automation have changed job requirements. CTE and other occupational programs have targeted these areas, though economists are divided over whether it actually exists, or they describe it differently.

“The idea of the missing middle is overblown — it exists in wages but not in jobs,” said Clive Belfield, an economics professor at Queens College. “The trouble with the skills gap literature is that the people typically making this claim are making it in a bad-faith way. Employers say, ‘We can’t get anybody to fill our skilled technicians’ jobs,’ but that’s because you’re paying $10 an hour and they might as well be a barista and have more flexibility.”

But James Bessen argued in the Harvard Business Review that changing technologies demand skills “that schools don’t teach and that labor markets don’t supply.” He contends that “employers have had persistent difficulty finding workers who can make the most of these new technologies.”

Sparks, the Ochsner executive, suggests the problem is more fundamental.

“We have students who don’t have internet at home, or don’t have computers, and the only way they interact is through apps, which is OK, but how are they going to work on a database, use a mouse, work on a laptop?” she said. “This is true of vulnerable populations that you’re trying to move into health care careers.”

Swinburn says that some families say they’re grateful to YouthForce NOLA for bringing career development back into school, but “the other half said, ‘I get what you’re saying, but my kids’ classroom has been named after someone who went to college and you’re saying they’re not going to college anymore,’” she said.

“We know and acknowledge the classist and racist history of vocational tech where kids did get tracked by income and race. But this is about building systems to overcome these inequities. This is about doing schools differently for all kids.”

Disclosure: This essay is part of a series of Future of Work stories sponsored by Pearson exploring how automation and evolving economic forces are impacting education from kindergarten through college.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)