The Age of Retraining: How Employers Are Working to Upskill Employees and Stave Off the Rise of the Machines

When economists and editorialists speak in worried tones about America’s “skills gap,” they’re referring to the mounting number of jobs that require some degree of technical know-how and the relative dearth of qualified candidates to fill them.

For Traci Tapani, the phenomenon is no mere abstraction. It’s a potential company killer.

“What we’ve started to see — and we started seeing this a decade ago, at least — is that the skills that people could bring to the job were different than they were in the past,” she told The 74 in an interview. “And it’s just progressively gotten worse. When we combine a very tight labor force with the fact that people don’t really have the skills you’re looking for, we’re in uncharted territory.”

Tapani is the president of Wyoming Machine, a family-owned metal fabrication business. The company has helped build everything from armored Humvees to retail fixtures and medical supply equipment, and it is frequently in the market for expert welders and production technologists. This is advanced manufacturing in what is still America’s industrial heartland, and the lack of trained job candidates has proven a major impediment to business.

Those problems are borne out at the national level. A 2015 report from the Manufacturing Institute, the research and advocacy arm of the National Association of Manufacturers, projected that 2 million manufacturing jobs would go unfilled by 2015, amounting to 60 percent of total openings over that span. In a survey accompanying the report, the vast majority of manufacturing executives agreed that they faced a talent shortage; among needed skills, new hires were found to be most deficient in math, computing and technology, and problem-solving.

Along with her sister and co-president Lori, Tapani decided that their company had to change its approach.

“We realized that we could sit still and just hope the people that used to exist, or the skills we used to see, would just magically reappear. Or we needed to adjust what we were doing to the current reality, which is that there’s fewer people available, and the people that are available often don’t have any kind of manufacturing experience.”

The Tapanis weren’t alone in this realization. Their relatively small organization — a few dozen employees in a facility located, somewhat confusingly, in Stacy, Minnesota — is part of a larger movement of employers large and small who are hoping to cultivate a more skilled workforce. That means constant reinvestment in employees, in the form of classes and skills certifications, to prepare them for the jobs that will emerge as manual work is increasingly mechanized. And the effort never stops: Workers often have to go back and acquire wholly new competencies every few years as technologies and methods change.

Call it a move toward a more protean economy. To stay professionally viable, employees can’t count on performing the same tasks over the entirety of their careers. To protect their bottom line, employers need to assist them in the continuous process of reinvention. And according to experts, that process needs to start early — perhaps as soon as kindergarten.

Workers are aging

Of course, there’s nothing new about worker retraining. In fact, as a human resources strategy, it’s supposed to be kind of played out. Wide-ranging analyses of federal job-training programs have shown little, if any, return on the millions of dollars spent to revive careers displaced by outsourcing and the chaotic business cycle. Meanwhile, as a generation of baby boomers begins to retire, we’ve been told that their places in offices and factory floors will be filled by hyper-capable machines that will soon be making paralegals redundant alongside taxi drivers and sales clerks. According to some estimates, the quickening development of artificial intelligence could endanger more than 70 million jobs in the next decade alone.

Americans are especially prone to this line of thinking. In a recent McKinsey survey of executives at major companies, a decisive 94 percent of European respondents said they believed that the skills gap would have to be addressed through a mixture of retraining existing staff and adding new hires. Just 62 percent of U.S. executives said the same; fully 35 percent of them believed that shortages in expertise could be addressed mostly or exclusively through taking on new, more skilled employees, a rate five times as high as among the Europeans. That regional difference could translate into mass layoffs based on age, as have allegedly occurred in big companies like IBM.

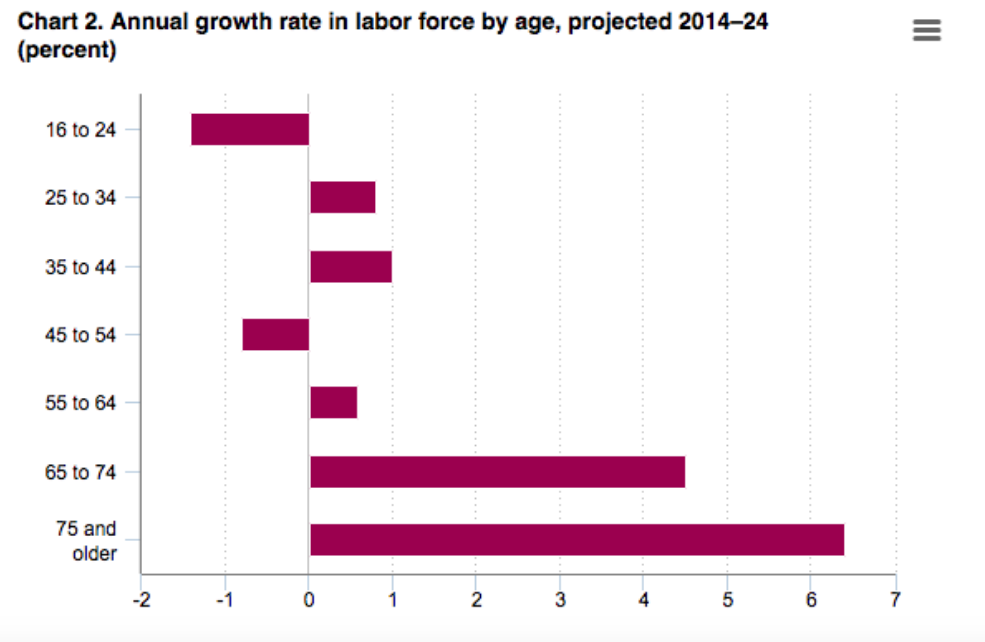

Widespread joblessness among older Americans could be a problem, given the country’s aging curve. Workers left behind when professional expectations shift tend to be those past the midway point in their careers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that by 2024, one-quarter of all working people will be over the age of 55, and 13 percent will be 65 or older.

Far from being an irrelevant policy solution, retraining could be a vital strategy for assisting the fastest-growing segment of the workforce. Even while conceding the possibly transformative effects of greater automation in the workplace, economists like Tyler Cowen have argued that these senior employees will need to be put to work in new roles. After all, the labor-force participation rate among older people has been rising since the 1980s, and surveys indicate that even most retirees would return to the workplace if given the opportunity.

Major companies are beginning to acknowledge these realities, and some have already dedicated enormous resources to addressing the problem. AT&T has pledged to spend $1 billion to supply roughly 100,000 of its employees with new training in data science, cybersecurity, and other novel fields as the telecommunications icon completes its transition from a landline-heavy business model to one based in mobile and cloud-based technology (“reskilling” is the preferred term).

Already a decade in the making, the company’s Future Ready initiative allows employees to access an online portal displaying open positions, their salary ranges, and the skills needed to fill them. Through partnerships with universities and online course providers like Coursera, those employees can take classes and earn skills certifications that are recognized throughout AT&T. In just a few years, nearly 60,000 workers have earned those certifications, and hundreds more have even enrolled in an online master’s program through Georgia Tech.

Cheryl Oldham, the vice president of education policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, says that moves like these are necessary steps at a time when few dare predict how new technologies will change the nature of work. While claims about the disruptive power of AI often run toward the fantastical, both organizations and their employees have to consider learning and skills acquisition a lifelong endeavor, she told The 74.

“AT&T is such a great example of an organization that has said, ‘Let’s be honest: We don’t know what it’s going to look like six months, six years from now.’ So, as people who want to support our workforce, we need to help them to be retraining and getting more education. Many employers who are sophisticated about this kind of stuff and are willing to invest in their workforce are thinking about this, and we’re in an exciting time right now for education and the ways we deliver training.”

Most organizations would likely prefer to transition existing workers to new tasks, Oldham explained, given the downsides of recruiting new talent. A bevy of studies on professional turnover demonstrate that the cost of replacing an employee adds up to roughly one-fifth of that person’s salary.

“It’s expensive to go out there and do the regular job posting, hope some people apply who are qualified,” she said. “Onboarding somebody, getting them up to full productivity, all of that is time-consuming and costly. And we’ve heard time and time again from folks we’re engaged with that not only is it costly, but they can’t get what they need.”

Business groups have also endorsed specific education policies to help solve labor shortages where they exist. After Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act, giving states significantly more autonomy to measure the effectiveness of schools, the Chamber issued a report urging employers and education leaders to emphasize career readiness when measuring student success.

High schoolers should not only be preparing for the academic rigors of college, the authors wrote, but also receiving career counseling and opportunities for work-based learning. The Council of Chief State School Officers has issued a similar call, noting that both colleges and employers have expressed concern at the lack of basic skills demonstrated by recent high school graduates.

But others argue that, in order to prepare today’s students to become tomorrow’s professionals, teachers need to start much earlier than high school. Indeed, a growing body of research suggests that schools should be inculcating “noncognitive skills” — persistence, focus, collaboration and self-regulation, among others — beginning as early as kindergarten.

A research review from the RAND Corporation has identified dozens of K-12 programs that not only show promise in promoting social and emotional learning but also are eligible for federal funding under ESSA. The interventions differ in their format and target student demographic, delivering classroom lessons to kids on everything from how to appropriately gain a teacher’s attention to how to practice good hygiene.

In 2016, the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project released a report summarizing much of the existing research on the labor-market value of noncognitive skills. Not only does the cultivation of greater social and emotional facility help kids avoid behavioral problems and attain greater levels of academic success, the report pointed as well to the rapidly rising status of workers who know how to communicate, switch between tasks, and work on a team.

It’s not hard to imagine how those attributes could also assist a worker in making a mid-career switch to new responsibilities, or even an entirely new job description. Lauren Bauer, one of the Hamilton Project’s researchers, told The 74 that the most successful “reskilling” programs can boost wages and lengthen careers by broadening expertise beyond the technical.

“Workplace-related noncognitive skill development benefits participants,” she wrote in an email. “Importantly, these skills are malleable — those participating in workforce development programs later in their careers can learn new skills, including noncognitive skills.”

‘They know they can leave’

At Wyoming Machine, Lori Tapani has gotten used to being creative in the talent acquisition process. With the supply of experienced manufacturing workers dwindling, she and her sister even began looking for candidates with experience in process-driven industries like service and fast food. But the shifting focus of their company toward more advanced industrial production means that even seasoned employees need to add to their competencies.

The manufacturing processes “are more computerized, so they’re more complicated, and people have to have some computer skills,” she said. “Even in small manufacturing, we’re starting to realize that there’s a ton of data … If I work on a shop floor and my quality isn’t good, it would be beneficial if a machine operator could get the raw quality data and analyze it himself — put it in Microsoft Excel and make a chart or try to figure out what it’s telling him. But very few people know what to do with [data], and … operators can’t use it to solve problems they’re seeing on the shop floor.”

That led the Tapanis, along with a consortium of other local employers, to begin a partnership with nearby Pine Technical and Community College. Together, they designed a customized training curriculum — led by professional educators, but accessed remotely via webcast — to help both new hires and longtime employees gain new nationally recognized credentials by learning skills such as auditing, maintenance, and safety. The continuous professional development not only makes participants more valuable to Wyoming, Tapani says, it also makes them feel more valued and confident.

“We actually think that when [employees] have those credentials, and they know they can leave, that increases their satisfaction,” she said. “They’re staying because they want to, not because they have to. Not everyone agrees with me. But you can’t be afraid of that. They know they can leave, and I know they can leave, but it makes us all behave in a more positive way.”

Disclosure: The 74’s coverage of the skills gap, the challenges and opportunities of better educating our future workforce, and efforts underway to improve local employment pipelines is underwritten in part by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)