Struggle for the Future: Schools Lag in Preparing Students for the Age of Automation

Thomas A. Edison Career and Technical High School, a sprawling, low-slung campus on a hillside in eastern Queens, offers its students many ways to prepare for a job.

On a summer-ish morning in early October, graphic arts students in a darkened classroom animated and edited their striking concoctions on propped-up 27-inch Wacom tablets. Not far away, a cybersecurity class sitting in narrow adjoining stations — calling to mind traders in a high-tech boiler room — worked to locate network breaches as the clock ticked down.

Perhaps the most cutting-edge technology was in evidence among participants in Model UN, an extracurricular activity simulating United Nations negotiations that high-ranking students often use to build their college résumés.

At Edison, it is offered as a regular class, mixing general and special education students. Classmates finish one another’s sentences in explaining how the course forced them to think deeply but also empathetically and pragmatically.

Two volunteers, a girl in electrical installation and a boy in collision repair and refinishing, gave examples of how the historical research required in the class related to their technical fields.

Principal Moses Ojeda nodded. “Soft skills,” he whispered.

The purpose of school in the age of automation

Ojeda’s appreciative aside caught a larger moment. As advances in artificial intelligence and robotics have increasingly substituted for human labor in performing routine tasks and sometimes those that required years of training, the premium on social abilities still beyond the reach of automation — like working well with others and adaptability — has shifted the way schools prepare students for their careers.

Over the past decade, educators and policymakers have introduced a myriad of policies and programming to meet new challenges — sometimes directly, as with career and technical education and expanded offerings in STEM and information technology fields, but also in the catchall effort to boost self-directed thinking through higher standards, instruction requiring close student engagement, and better tests.

Some of this work lacks a common vocabulary. Social skills are often called soft or non-cognitive skills, or social-emotional skills, or personality traits, and refer to qualities ranging from creativity to perseverance. The vagueness may signify that schools haven’t fully internalized their role in “workforce development,” a term whose colorlessness masks its importance.

Education, business, and political leaders generally agree that, notwithstanding successful local initiatives and a move away from rote instruction by more skillful teachers, the broader effort to develop the future workforce has been unsystematic, reflecting regional differences as well as inequalities of race, gender, and income. Gaps in achievement translate into gaps in preparedness as students grow up in poor areas of cities and rural America.

The rise in importance of non-academic abilities reflects an understanding that students need to be prepared differently but exposes a lack of coherence in how to build those competencies.

“The very term soft skills reveals our lack of understanding of what these skills are, how to measure them, and whether and how they can be developed,” said David Deming, an economist at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, in a 2017 paper that found social ability to be increasingly important for high-paying jobs.

Philosophical differences about the purpose of school may have slowed the adoption of new approaches focusing on “training.” Those with less pragmatic outlooks have objected to framing education’s goals in economic terms. And practitioners who work with disadvantaged populations can view phrases like “workforce development” as having little relevance given the daily challenges of poverty.

Four-year college completion rates have risen sharply over recent decades, but it is still the exception — roughly 1 in 3 students earns a four-year degree — and dropout rates among less affluent students remain high, but some traditionalists continue to uphold a “college for all” ideal, as do education reformers.

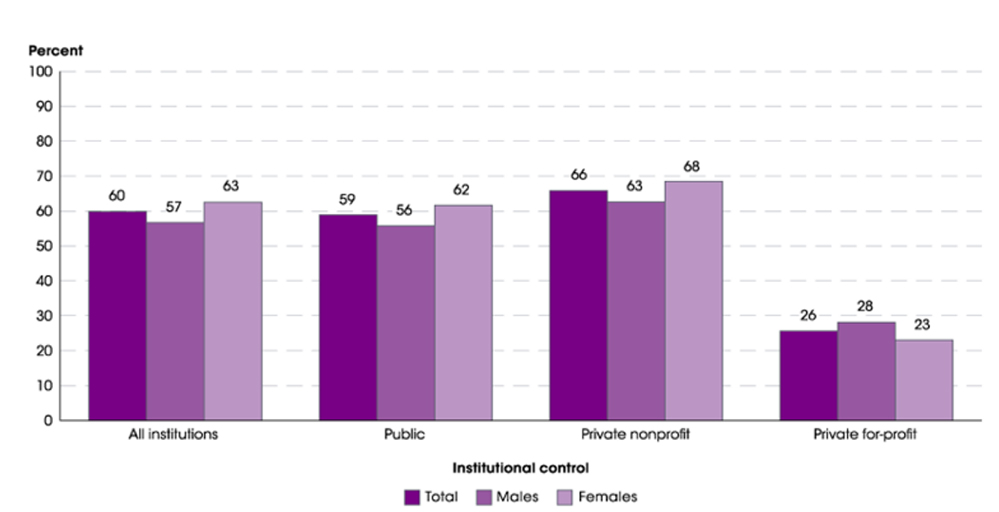

Students graduating with bachelor’s degrees

Sociologist Jal Mehta suggests in a 2015 essay that the “elevation of the economic purposes of schooling over its many other purposes” occurred fairly recently, sparked by the recession-era publication of A Nation at Risk, a landmark 1983 report that warned of a crisis in American schooling.

“The human capital approach,” Mehta writes, “has powerfully reshaped the divisions in educational politics and has focused the aims of schooling tightly around learning that has economic value.”

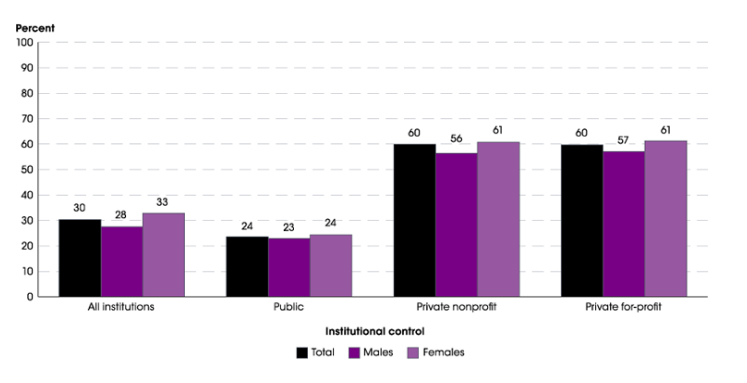

Students graduating with associate’s degrees or certificates

“Human flourishing is one of the basic purposes of education,” said Anthony Carnevale, who directs the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University. “In the end, though, if you don’t prepare people for a job, they’re not going to flourish.

“Education has a different mission now since the 1980s,” he told The 74. “It’s still trying to figure how to be responsible for that mission.”

‘They stuck with it’

At Thomas Edison, students can select from 11 separate programs of study, ranging from digital media to robotics. (The school also offers a traditional academic course of study.) Its breadth, Ojeda says, has made Thomas Edison a leading source of teaching talent for other CTE schools in New York City. Sixteen teachers at the school, out of about 120, went to school there.

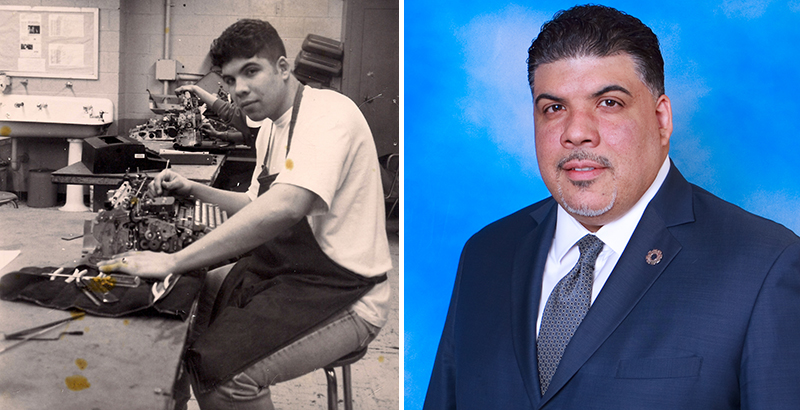

As did Ojeda. A strong presence, thickly built in a close-fitting suit, he said the school succeeds by reinventing itself.

“My mindset is always, ‘What’s going to make us stand out five years from now?’” he said, giving the new drone curriculum as an example. “I don’t want to just teach these kids how to fly the drone; I want to teach them how to build it, the theory behind it. Because when Amazon decides to release the drones [to make deliveries], I’ll have a workforce here ready to get those jobs.”

The potential of CTE programs to provide a bridge from high school to a college credential and meaningful work has for years attracted bipartisan support from elected officials — perhaps more so than with any other educational issue — and backing from business.

“We don’t need to talk about what we don’t agree upon but what we can agree upon,” said U.S. Rep. Glenn Thompson. The Pennsylvania Republican, who co-chairs the Congressional Career and Technical Education Caucus, helped lead a bipartisan coalition across the usually embittered ground of education policy to reauthorize the country’s CTE funding bill, reducing restrictions on $1.2 billion in grants available to states.

“We need to make CTE more accessible, and we need to have the ability to make it more effective. More than hours, more than a certificate, it’s a good family-sustaining job,” said Thompson, who co-sponsored the House version of the new law.

A little more than 80 percent of high school graduates in 2013 earned at least one credit in a CTE course — non-vocational students take courses like accounting or learning to use Microsoft Excel — a decline from 87.9 percent in 1992. But benefits were concentrated among students who took multiple courses at more-difficult levels, according to a research overview by the evaluation group MDRC.

The group reported that evidence for some popular approaches, like apprenticeships, remained unclear or mixed, but also pointed to studies finding dual-enrollment programs, in which students earn college credit while in high school, and technical schools that enroll all nearby CTE students, improved graduation rates and other outcomes.

“One key aspect of the ‘new CTE’ is that it is now being thought of as preparation for college and career, and no longer as college or career,” Rachel Rosen, lead author of the MDRC report, said in an interview with The 74.

She said CTE “has the potential to level the playing field for a lot of kids” but added that there are “a lot of issues in the details of delivery that will determine whether or not it’s a mechanism for maintaining existing inequities — that’s the big question right now.”

Some of the lift for programs — which often vary in quality within the same school — is cultural. Ojeda said that as the Model UN team has improved, “they’re being invited to Yale, to Brown University. But it was a culture shock for these kids when they first arrived. They did not fit the criteria of the kids who compete at these universities.”

Just over 40 percent of the school’s students are black or Hispanic. The largest group, at 46 percent, is Asian, mostly from South Asia. The school’s poverty level is 78 percent, about the citywide average.

“But they stuck with it,” Ojeda said. “Now the conversation is, ‘Look out for those Edison kids because they will take you down.’”

Rise of the robots

K-12 schools in the U.S. were only recently charged with preparing most students for skilled, non-repetitive work or a college degree. As recently as the early 1980s, according to Carnevale, about 70 percent of jobs in this country required a high school diploma or less.

By the 1990s, he said, the proportions had reversed. “The share of those who could still get a decent job with a high school education diminished to 20 percent, almost all male,” he said. Workers with only a diploma can earn a living wage in mechanics, construction, and installation and repair jobs.

The return on education is high. Male workers 25 and over with only a high school diploma had median weekly earnings of $810 in the second quarter of 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while those with bachelor’s degrees earned $1,372. Men who held an advanced degree had median weekly earnings of $1,808, although the median for women with advanced degrees was $500 less. These educational and gender disparities widened at higher income levels.

Advances in artificial intelligence and computing power have enabled industries to automate tasks that were central to many jobs previously open to high school degree holders or non-finishers, like the “predictable physical work” that was the foundation of manufacturing for generations. (The impact of automation on U.S. manufacturing loss is not straightforward, however.)

Automation will create new jobs and operate alongside people, as it does now, but some fear that it will outpace job creation. A 2013 study estimated that nearly half of the country’s jobs could be performed by smart machines within 20 years, while the Boston Consulting Group reported in 2016 that almost 40 percent of the automotive industry was already automated.

Smart machines also began to perform white-collar tasks that demand years of human training.

“AI is getting really good at reading radiology images,” tech entrepreneur Andrew Ng said at a conference last year, suggesting that new radiologists could expect “a perfectly good five-year career” before machines replace them.

Problems and possible solutions

Inequality shadows K-12 preparation for college and careers, especially for students from lower-income families, but also for women.

Stanford University’s Sean Reardon has shown that racial and ethnic achievement gaps, while still large, have narrowed over time, but the gap between high- and low-income students has increased since the 1970s by between 40 and 50 percent, a difference equating to three to six years of learning by some measures.

Those gaps anticipated later failure in higher education, a study of college graduation rates suggests.

Using extensive demographic and personal data collected over several decades by the University of Michigan, a researcher there named Fabian Pfeffer calculated that the college graduation rate for students born in the 1980s — those in their 30s now — to families in the top 20 percent of income was 49.8 points higher than for students in the bottom 20 percent. And the gap is growing: Pfeffer determined that the rate for top-quintile students born a decade earlier, in the 1970s, was 39.5 points, about 10 points narrower.

Pushing unprepared students to college, say experts, often results in a long arc of debt, insufficient skills for a job that provides a stable income, and little or no savings.

“These are the consequences of schools that are supposed to be readying students for the middle class but actually do very little,” said Robert Schwartz, former dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and co-founder of Pathways to Prosperity, an organization that helps students find careers.

Success rates at two-year colleges are also daunting. About 39 percent complete their studies within six years, a figure that drops to below 1 in 3 among those required to redo high-school-level work in remedial classes.

“We need to get kids through to a post-secondary credential by the time they’re 19 or 20,” Schwartz said. Giving students college and work experience while in high school makes career success far more likely.

“Continuing to say to all kids, ‘You have got to get a four-year degree if you’re going to make it,’ is educational malpractice,’” he said.

The Common Core State Standards movement, which launched in 2009 with the backing of the Obama administration and was at one time supported by leaders in 41 states, was meant to help fill the breach.

An early report by Achieve, an education nonprofit that helped mobilize the push for more challenging standards, concluded, “While students and their parents may still believe that the diploma reflects adequate preparation for the intellectual demands of college or work, employers and postsecondary institutions know that it often serves as little more than a certificate of attendance.”

Governors and state education chiefs said the standards would help students to graduate from high school “prepared to succeed in entry-level careers, introductory academic college courses, and workforce training programs.“

Political resistance and bureaucratic obstacles resulted in uneven adoption of the standards among states. Researcher Tom Loveless at the Brookings Institution found small gains on the National Assessment of Educational Progress in states that more fully implemented the standards. He has also reported on the larger pattern of stagnation on the national exam.

Several factors, including questions of how well NAEP items lined up with the standards, made it impossible to conclude that they had a causal effect on outcomes, however.

In Arizona, where the state education chief led a successful effort to repeal the standards, local industry played a countervailing role, said Lisa Graham Keegan, chief executive of the state’s Chamber of Commerce foundation and a former state superintendent.

“The biggest contribution business makes is to encourage the jump” to better standards and tests, she said. “They’re saying, ‘We need to employ kids with these sets of skills, and you’re not helping them get them.’”

The opportunity gap for girls

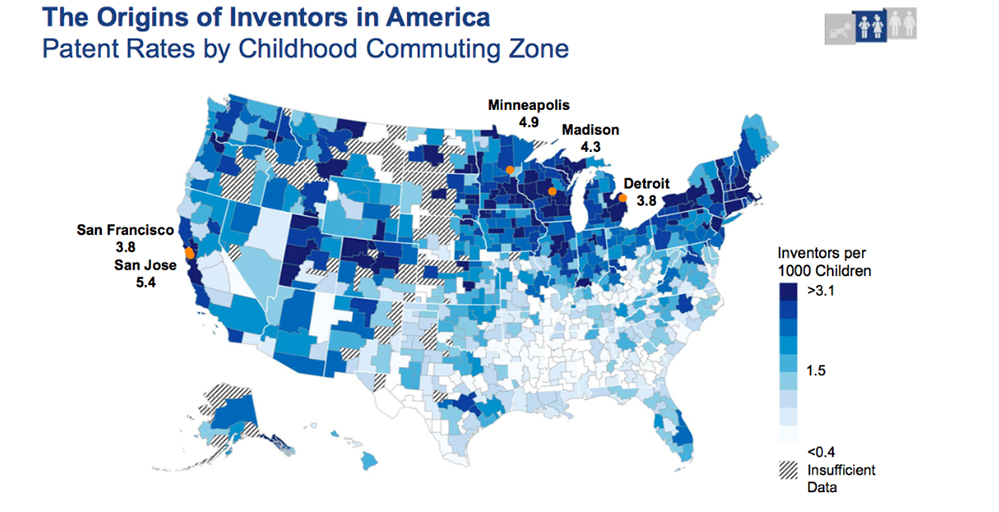

The nationwide push to increase the number of women in STEM fields has produced female biologists but few additional engineers. Harvard economist Raj Chetty has shown that affluent students are 10 times as likely to win patents as those whose families earn below the median income, and girls comprise just 18 percent of inventors.

If minority, low-income, and female students went on to win patents at the same rate as boys from families in the top fifth of income, he wrote, “the rate of innovation in America would quadruple.”

He also found that girls were more likely to invent if they lived in neighborhoods where innovation happens, including those around Silicon Valley and Minneapolis, which is a leader in producing medical devices. Exposure to female inventors at school assemblies, on field trips, or through social media increased the likelihood that a girl would go on to become an inventor herself.

Girls typically outperform boys on measures of soft skills like self-control, conscientiousness, and collaboration, which may prove an important strength in future job markets.

A blend of soft and technical proficiency was evident in Daisy Paiz, a senior at Thomas Edison in the collision repair program. Sharp and confident in plastic work goggles and a short-sleeved blue mechanic’s shirt embossed with her name, Paiz said she liked to help boys in the shop and loved the school (“everyone is so kind”). She was unabashedly entrepreneurial.

“I want to be the head of everything at my company,” she said. “I want to run everything.” She suggested she wouldn’t limit herself to the automotive industry, though it is expected to provide opportunities for workers with more advanced computer skills.

Artificial intelligence will improve access to education

Speculation about future job trends by economists and at education and technology gatherings — and in fright pages listing jobs about to be rendered extinct by the meteorite of technology — centers on a few ideas. A 2017 survey of more than 1,400 experts identified by the Pew Research Center found that most believed education and training will successfully provide the skills needed for jobs that emerge in the future.

Pew respondents said education needed to capitalize on advances in artificial intelligence to become more customizable. Universities would continue to offer the richest learning experience, but job preparation would migrate online, they said, offered by schools or employers or other providers, allowing students and workers to earn job credentials more flexibly and augment learning throughout their lives.

The specificity of this vision is ahead of the evidence, but its outlines were supported in a 2017 book-length review by the National Science Foundation of the latest evidence and industry innovation.

The economists who wrote the study concluded that advances in artificial intelligence and robotics will increase productivity and quality of life, but “humans are still more effective than computers at many tasks, especially those that require creative reasoning, non-routine dexterity, and interpersonal empathy.”

The technological gains transforming much of daily life offered “new and potentially more widely accessible ways to access education,” they wrote.

The increasing value of soft skills is backed by evidence

Deming, in his 2017 paper, builds on Nobel economist James Heckman’s argument that because traditional measures of intelligence explain only some of the difference between the earnings of similar workers, “productivity is likely influenced by multiple dimensions of skill” — not just cognitive ability.

Other studies have shown that the value of cognitive ability — independent of social competencies — reached a plateau after 2000.

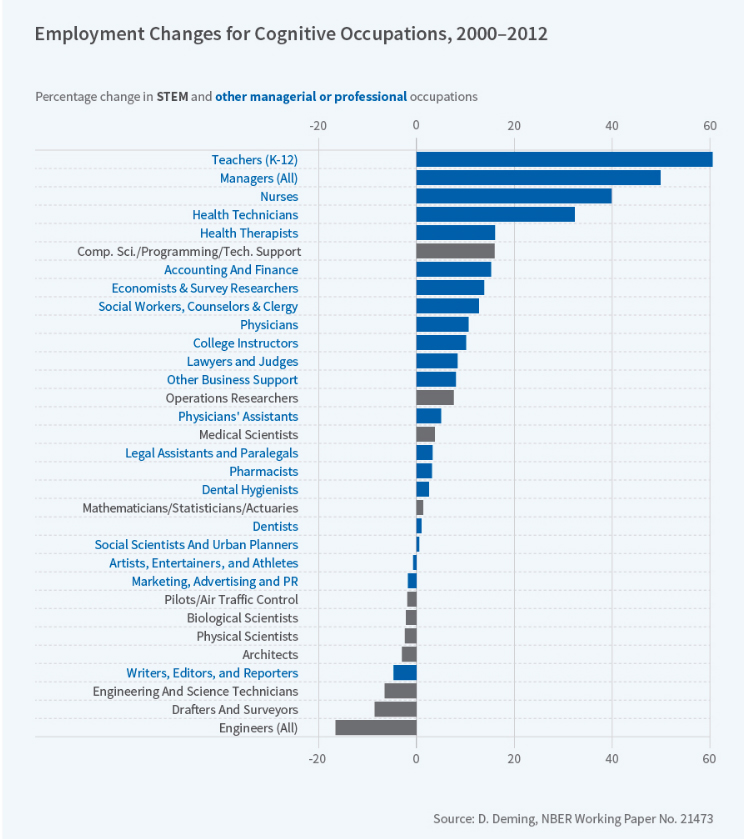

Analyzing employment trends between 1980 and 2012, Deming found that jobs requiring extensive interaction, such as teachers, managers, and nurses, grew by nearly 12 points as a share of the labor force, while analytical positions that required few social skills, including some engineering jobs, declined. Wages for “high math, low social skill” occupations increased by 5.9 percent, compared with 26 percent growth for “high math, high social skill” openings.

“Computers are still very poor at simulating human interaction,” Deming wrote. “Reading the minds of others and reacting is an unconscious process, and skill in social settings has evolved in humans over thousands of years.

“Such non-routine interaction is at the heart of the human advantage over machines.”

Disclosure: The 74’s coverage of the skills gap, the challenges and opportunities of better educating our future workforce, and efforts underway to improve local employment pipelines is underwritten in part by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)