For the Smartest Students, a Tale of Two Cities: What Enrollment Numbers Reveal About How NYC’s Top Boys & Girls Are Sorting Themselves Into Different Schools

Updated May 3

The New York Times reported the news on May 3, 1969, Page 40:

“Boys at Stuyvesant High School can look forward to a new extracurricular attraction next fall — a girl … The only boys who are unhappy about it are this year’s graduating seniors.”

So began the era of coeducation at the most prestigious public high school in the city, if not the nation.

Stuyvesant had refused to allow a 13-year-old from Brooklyn named Alice De Rivera to sit for its entry exam even though she’d aced a similar test at Bronx High School of Science.

De Rivera won the right to be described as an “extracurricular attraction” after filing a suit alleging Stuyvesant’s admissions policy discriminated against female students. Her family moved before she could attend, but a dozen girls entered that fall.

Bronx Science, the elite school that would have entailed a three-hour daily commute had De Rivera accepted its offer, first opened to girls more than 20 years before. A third high school that admitted students based on a test, Brooklyn Tech, would not become coed until 1972.

Nearly a half-century later, these schools, and five more that adopted the same exam — the Specialized High School Admissions Test — can hardly be imagined without female students. Like their male classmates, many go on to Ivy League colleges and other major universities.

Yet even in success their numbers have always remained disproportionately small, around 42 percent for the past five years, while girls are 48.5 percent of all city students.

By contrast, the most selective city high schools that admit students based on factors like grades and state test scores, rather than an entrance exam — the so-called screened schools — are nearly 60 percent female.

An analysis by The 74 found that a little less than 10 percent of the city’s high school students were sorted into either specialized (15,452) or the most competitive, entirely screened schools (14,986) in 2016–17. (We didn’t include large neighborhood schools that enroll many top students but are at least partly unscreened.)

In addition to being largely male, the specialized schools are heavily Asian, more economically disadvantaged, and science- and math-focused, while the most popular, female-dominated screened schools are more white and affluent and perceived as offering a rounded liberal-arts curriculum. The specialized schools have income diversity — more so than many other top-ranked high schools around the country — but low levels of racial integration.

Changes in the racial, ethnic, and economic makeup of the schools over the past five years were nominal. The ratio of boys to girls was the same in 2016–17 as it was five years ago.

Racial disparities vs. the lack of girls

The gender imbalance in schools attended by high-performing students was overshadowed in the most recent wave of headlines calling out stark racial and ethnic disparities in specialized school admissions. These inequities were widely blamed on use of the specialized test as the only criterion for admission. Black and Hispanic students make up 70 percent of city students but only 10 percent of those in specialized schools like Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Tech — a consequence of having attended ineffective schools and lacking access to prep classes and coaching, both critics and supporters of the test agree. In a survey last fall, 43 percent of Stuyvesant students said they prepped for the test for six months or more.

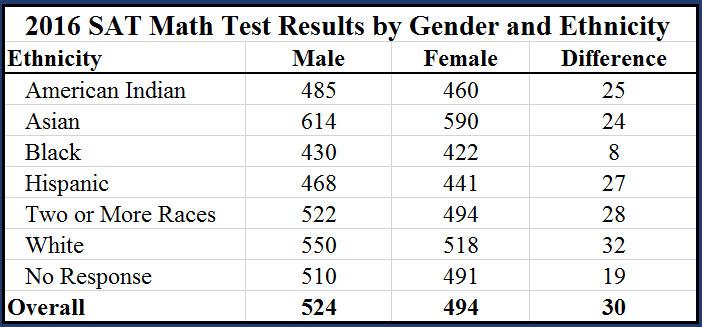

The smaller numbers of female students in elite tech high schools probably also reflect the hold of traditional views about the subjects girls are interested in and good at. These views may affect their performance on high-stakes tests. (Additionally, a recent study found that girls do better on open-ended questions, while boys are better at multiple choice. All but five of 94 scored questions on NYC’s specialized high school entrance exam are multiple choice. Other studies find that passing the test, and attending a specialized school, does not improve SAT scores, college graduation chances, or other outcomes.)

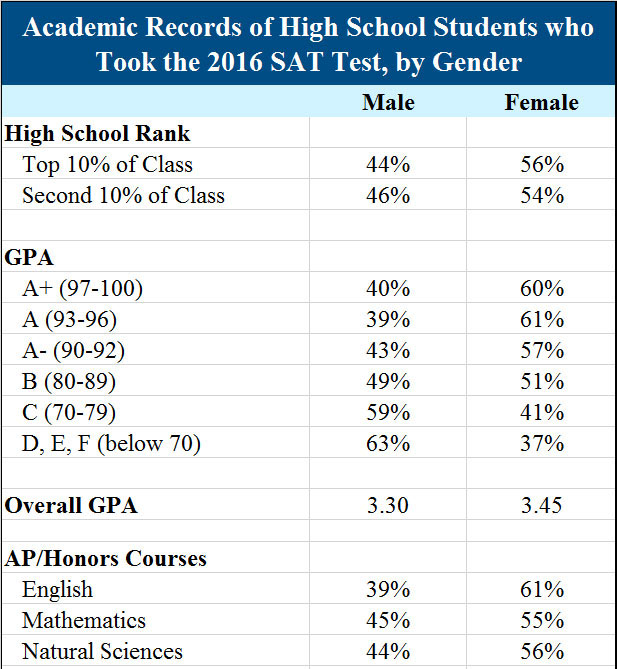

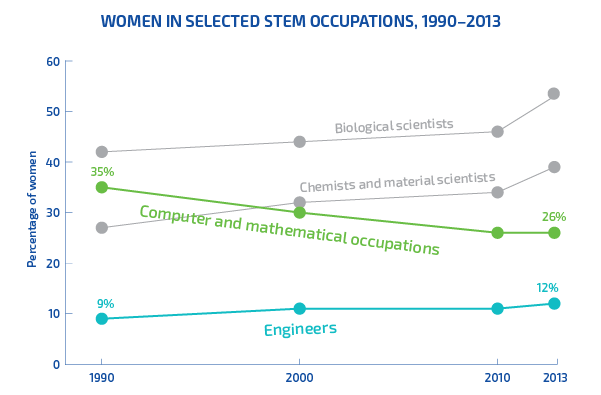

The heavy science and math focus of most of the specialized schools may still appeal only to a minority of girls, advocates acknowledge, despite more than a decade of corporate and philanthropic initiatives boosting STEM instruction — and even though girls outperform boys on most measures of academic achievement.

“Girls, when they’re up for the challenge, the biggest impediment they have is believing that they have a right to be there and that learning these skills is going to change the world,” said Talia Milgrom-Elcott, executive director of 100Kin10, which seeks to expand education in STEM fields. “The problems we face are really big, and only a tiny percentage of our population has a chance to solve them.”

Two tiers

Using state and city data, The 74 determined that the 20 entirely screened schools with the most applicants this year enrolled roughly the same population as that of the specialized schools that admit based solely on the test.

Enrollment in the 20 schools was 57 percent female, flipping the gender ratio of specialized schools, and nearly all of the schools were humanities- or lightly science-themed. In the past, these popular screened schools attracted many students who declined offers from the specialized schools. An NYU study of specialized schools by Sean Corcoran and Christine Baker-Smith found that between 2005 and 2013, for instance, 15.2 percent of students turned down specialized school offers to enroll in esteemed Townsend Harris High School, which has been dubbed “the Stuyvesant of Queens.”

Many who won admissions through the specialized test opted for LaGuardia High School, a specialized performing arts school that admits students based on auditions. If it were grouped with the 20 screened schools that also forgo a test, LaGuardia would lift the portion of female enrollment among them to 60 percent, in part because of its large size and 75 percent female composition.

In addition to gender, the screened schools are whiter than specialized schools (30 percent vs. 24 percent), considerably less Asian (23 percent vs. 61 percent), and slightly less poor (50 percent vs. 51 percent). The screened schools are also more black (17 percent vs. 4 percent) and Hispanic (26 percent vs. 6 percent), though neither figures are close to system averages of 26.6 percent and 40.6 percent, respectively.

And because the screened schools tend to be modest in size, with an average enrollment of 749 students, a few of the larger ones make the rest look more integrated and less affluent than they actually are.

For instance, if the list didn’t include Benjamin Banneker Academy and the Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics, two schools that serve large minority populations, the percentage of poor students among the remaining screened schools would drop by six points, to 44 percent, and the white population would increase by 5 points, to 35 percent, nearly two and a half times the citywide average of 14.7 percent.

The test

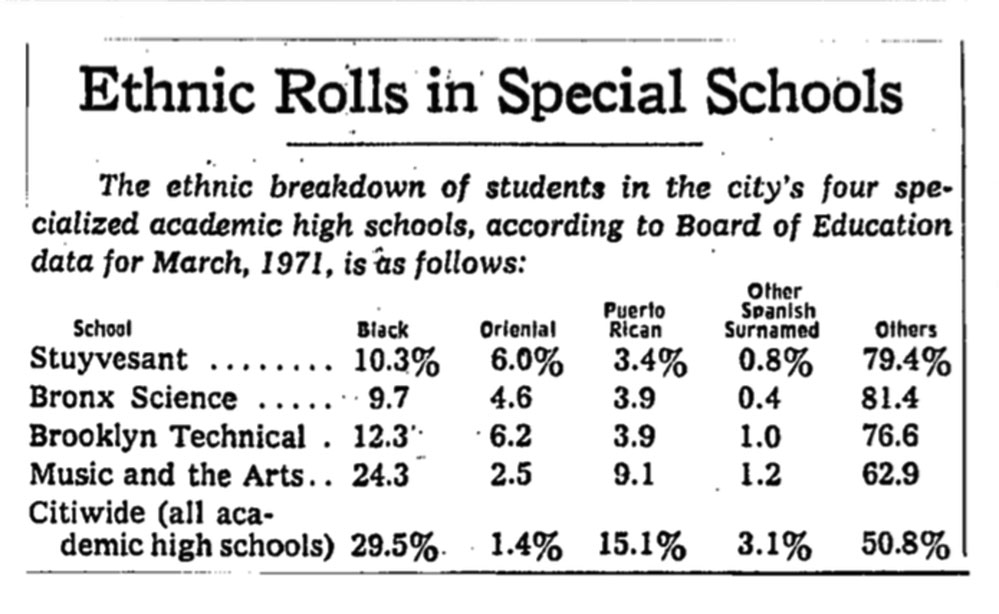

Not long after girls began attending Stuyvesant in the early ’70s, the exclusiveness of specialized schools was challenged by an outspoken Upper West Side superintendent — the city’s first Puerto Rican district leader — who described Bronx Science as “a privileged educational center for children of the White middle class” whose admissions test worked to “screen out” minority students.

When the schools chancellor appointed a commission to investigate, two state legislators representing the Bronx — backed by 13 senators and 41 assemblymen from the city — successfully sponsored a bill requiring the existing “special” or specialized schools (exempting LaGuardia, then known as the High School of Music and the Arts) to continue to admit students “solely and exclusively” with a “competitive, objective, and scholastic” exam.

Black and brown students have not typically scored high enough to enjoy more than a marginal presence in the schools. In 1971, blacks were 10.3 percent of Stuyvesant students and “Puerto Rican” and “Other Spanish Surnamed” were 4.2 percent. Interestingly, Music and the Arts, which still bases admissions on auditions, had nearly three times as high a percentage of black students then (29.5 percent) as now (11 percent).

This year, just 21 black students are enrolled at Stuyvesant among a total population of 3,368. Of the 12,225 black and Hispanic students who took the specialized test this year, just 527, or 4 percent, were offered places in any of the specialized schools.

Chinese and other Asian students are now 61 percent of all specialized school students and 73 percent of those at Stuyvesant, even though Asian nationalities have constituted the poorest ethnic group in the city for several years. The NYU specialized school study found that 28.1 percent of specialized offers between 2005 and 2013 went to students who spoke Chinese at home.

Efforts to achieve racially and ethnically balanced specialized school placements have been advanced in lawsuits, legislative proposals, academic research, and tweaking of education policy, but have changed little.

City officials said they did not have a plan targeting equity in specialized schools but believed Mayor Bill de Blasio’s signature Equity and Excellence for All agenda would create a wider pool of qualified applicants.

“We are committed to making our specialized high schools more reflective of New York City, and we know there is more work ahead,” said Department of Education spokesman Doug Cohen. “That means giving students the foundation in elementary and middle school that they need to successfully apply to a specialized high school if they choose, but also ensuring that students receive rich and rigorous instruction, including AP and college-prep courses, at every New York City high school.”

Last month, following the news that only 10 black and 27 Hispanic students were admitted to Stuyvesant’s 902-member freshman class next fall, two state senators announced a modest set of proposals on the steps of City Hall that they hope will better prepare students who need it. Although the plans would create more test prep opportunities, they don’t include measures that would loosen the test’s hold on admissions.

“Giving a little test prep in seventh or eighth grade isn’t going to make up for years of segregation,” said Lazar Treschan, director of youth policy at the Community Service Society, which has proposed allotting specialized seats to top students from all middle schools. “Diversity is the greatest strength of the city, but it’s also really complicated.”

Alternatives to the admissions test that used grades and test scores would boost offers for girls, as the enrollment of the screened schools suggests. Girls outperform boys on these criteria.

Larry Cary, president of Brooklyn Tech’s Alumni Foundation, a powerful defender of test-based admissions, argued that the lack of higher-scoring minority students reflects the failure to educate underserved children from the start.

“Unless we have a revolution in this country, change is going to be on the margin,” he said. “Fundamentally, the problems are much bigger than what these bills are designed to address.”

Improving access for girls wasn’t mentioned at the rally at all. One of the lawmakers offering fixes for the racial and ethnic imbalance was state Sen. Toby Ann Stavisky, herself a graduate of Bronx High School of Science in the 1950s.

“I know the test is fair and gender-neutral,” Stavisky said afterward, though there is no research showing that to be true. “I think girls are told don’t bother yourself with science or the STEM subject.”

Stavisky’s Queens district produces many Chinese-American students who have excelled at test-based admission and travel across the city every day to attend Stuyvesant in lower Manhattan or to Bronx Science.

“When I went, they were accepting one girl for every five or six or seven boys, but I never felt stigmatized,” she said of her experience at Bronx Science some 60 years ago.

The sorting

The de facto sorting by gender among high-achieving New York City students reflects deep-rooted differences in the way boys and girls perceive themselves, experts say, and may persist through the selection of college majors and careers.

Research shows that girls and boys start school with roughly equal ability but by the later elementary grades boys have pulled ahead, especially among the best performers. This growing gap is not limited to more conservative areas of the country or outdated curricula.

“Girls are losing ground in math in every region of the country, every racial group, all levels of the socio-economic distribution, every family structure, and in both public and private schools,” wrote economists Roland Fryer and Steven Levitt in a 2009 analysis. “By the end of the sample, girls do significantly worse than boys on every math skill tested.”

“Something is happening from the very early ages that is diminishing girls’ confidence in math, kind of in their own intellectual abilities in general, despite the fact they’re doing much better in reading and ELA.”

— Joseph Cimpian, a professor at NYU’s Steinhardt School of Education

Fryer and Levitt don’t point to a clear cause, but other studies have cited lower expectations for girls, teachers rating boys as more talented when a girl performs just as well, boys rating their ability 27 percent higher than girls do, and what psychologists call “stereotype threat” — in this case, the fear of being judged by a negative stereotype about women’s math ability.

“We see that girls and boys, when they enter school around age 5, both think their gender is a smart gender,” says Joseph Cimpian, a professor at NYU’s Steinhardt School of Education who has studied academic gender gaps. “But then around 6 or 7, girls begin to think maybe they’re not as smart as boys are.

“Something is happening from the very early ages that is diminishing girls’ confidence in math, kind of in their own intellectual abilities in general, despite the fact they’re doing much better in reading and ELA.”

Seventh-grade girls in New York City public schools outperformed boys by some distance in English last year. In math, 36.9 percent of girls scored at the highest levels — three and four — two points higher than boys, while 15.8 percent scored at level four, which was 0.4 percent higher than boys. (It’s possible that the very highest performers were largely male.)

But while more girls tend to take the specialized test than boys do, fewer get offers. Last fall 14,513 girls and 13,693 boys sat for the test; 15 percent of the girls and 20 percent of the boys received offers from the top specialized schools.

The confidence gap

“Even if they get in, they don’t go,” said Laura Zingmond, a past member of the mayor’s Panel for Educational Policy and a senior editor at InsideSchools. Zingmond believes girls are often ambivalent about specialized schools.

Her view accords with the NYU study, which found that girls were less likely to be admitted and a “substantial” 10.8 percentage points less likely to accept an offer.

The analysis also found that while more black and Hispanic students applied for admission than their academic records predicted, fewer girls did.

Zingmond calls the specialized test “sort of the culmination of the bias that has meant every step of the way you’re losing girls.” She cites an influential study by psychologist Sian Beilock, now the president of New York City’s Barnard College, that found that math anxiety in elementary school teachers depresses the performance of female students, but doesn’t affect boys.

“It’s cultural,” Zingmond said. “Boys are more likely to go for the answer even if they’re not sure of it. Girls are more sure to double-check, triple-check before they raise their hands.”

Ruth Lacey, principal of Beacon High School — a highly sought-after screened school in midtown Manhattan — believes that girls can overcome obstacles blocking their way.

“If I put Beacon Science or Beacon Technology above the door and gave a test, I’d get more boys,” says Lacey, whose school is 64 percent girls. “But girls are strong. Give them a chance to have a voice and they can dominate. That’s part of the whole movement in the country.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)