New Study Shows States That Veered From Common Core Adopted Weaker Academic Standards

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new numbers, research, and reporting. Go Deeper: See our full series.

Academic standards for both math and English language arts have suffered in states that veered away from the Common Core, according to a new study. While standards across the country made progress over the past decade, the minority of states that have attempted to break from the controversial initiative have failed to improve upon it, the authors find.

The lengthy study was released today by the Fordham Institute, a right-leaning think tank that has published previous reviews of state content standards. Those standards guide classroom instruction in a range of subjects by indicating specific knowledge and skills that should be mastered by various grade levels. Though the rigor of a given set of standards can be assessed from afar, the authors note that the quality of teaching depends ultimately on implementation by schools.

For this report, Fordham commissioned two teams of experts — one for mathematics and one for reading — to study the quality of academic standards in states that either never adopted the Common Core or significantly altered them after adoption.

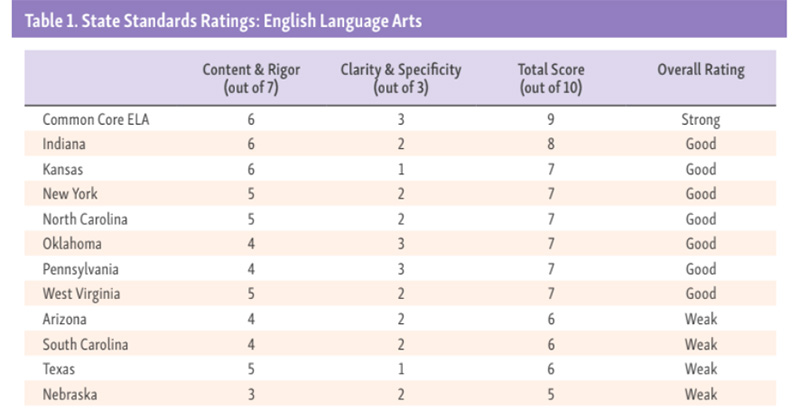

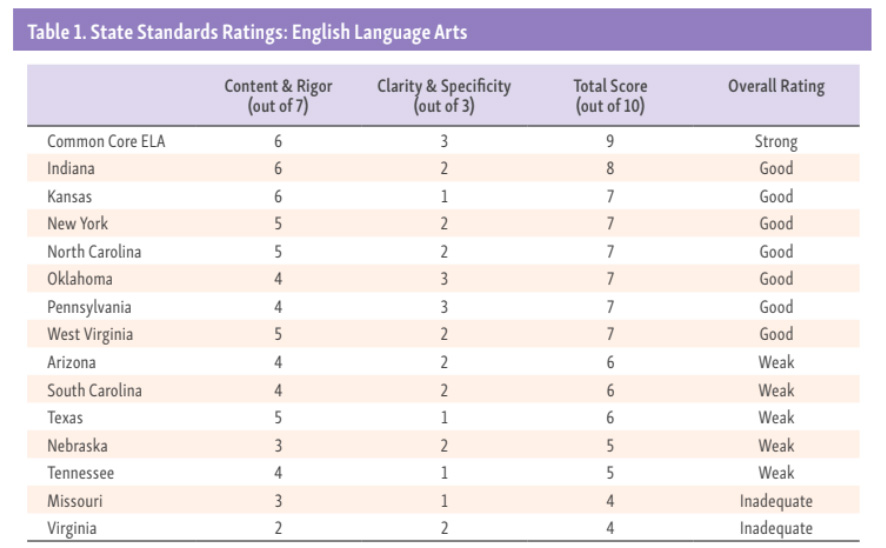

Overall, the reviewers agreed, the Common Core remains the gold standard, receiving a 9/10 score for both math and English in content, rigor, clarity, and specificity. In no state did they judge the local alternatives superior to the Common Core in either math or reading. In fact, a majority of the 15 states that rejected the Common Core had installed standards that the reviewers found in some way deficient.

“It does seem like there are significant risks associated with trying to do better than the Common Core, and in general, states that decided to change [the standards] in most cases made things worse rather than better,” David Griffith, a Fordham policy associate and co-author of the report, told The 74 in an interview. “There’s a very delicate internal logic to the way that most state standards, including the Common Core, are laid out. It’s pretty dangerous for states to jump in and try to tinker with that, because in many cases, they don’t fully understand the consequences of the changes they’re making.”

Developed as a nonpartisan initiative of the National Governors Association, the Common Core was originally seen as the culmination of a decades-old move toward a uniform set of rigorous content standards that grew out of the school accountability movement of the 1990s. When the Obama administration incentivized states to adopt the standards as part of its Race to the Top grant program, however, they became for many a symbol of federal meddling in state and local education efforts.

Conservative politicians in many states began fulminating against the initiative, either pushing state governments to reject the Common Core standards outright or else repeal them if they had already been put into place. To take one example: Legislators in Missouri passed a 2014 bill, later signed by Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon, to revise the standards after they had become enormously controversial; as in many states, activists characterized them as an expressly political Trojan Horse for, among other things, Islamic indoctrination.

Today, Missouri is one of two states — along with Nebraska — whose math and English standards were separately rated as “weak” (in need of serious revisions) or “inadequate” (in need of a complete rewrite).

Part of the problem, Griffith explained, is that the Common Core already expressed the consensus of experts in math and English. If lawmakers wanted to distinguish their own state standards from the maligned federal alternative, they would have to break with that consensus to some degree. Though some have complained about the complexity of certain Common Core-aligned math materials, particularly at the middle school level, Griffith identified that subject as a particular example of the perils of dumping the standards.

“There’s a standard algorithm for division, there’s a standard algorithm for addition and subtraction,” he said. “And there’s a reason why that algorithm is standard — it’s because it’s the most efficient way to add or subtract or divide. And if you’re going to deviate from that, then you’re necessarily going to be moving toward something that’s more mathematically questionable, or at the very least, you’re going to be avoiding what pretty much everyone everywhere agrees is the right way to do subtraction. So it’s kind of a case of cutting off your nose to spite your face.”

Even after the massive backlash, the study finds that the nation’s Common Core ordeal unfolded largely for the greater good. Among the majority of states that either accepted the standards wholesale or made only minor changes, schools are working with much stronger academic guidelines than were in place a decade ago, Fordham argues. A few — the report singles out Massachusetts and California for special attention — have supplemented the standards with hundreds of additional grade-specific examples that can assist teachers.

And states like Texas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma, which never adopted the Common Core, have nevertheless implemented some of its elements, such as the Standards for Mathematical Practice. While both instructional teams still endorse the Common Core as the best example of statewide academic standards, they note several positive trends that have developed in states that moved away from them, like a heavier focus on writing and arithmetic in early grades.

“In general, many of the ideas that are in the Common Core are bigger than the Common Core — they’re ideas about how math ought to be taught in the view of math experts,” said Griffith. “So you can talk about [the influence] of Common Core, but I would also say that, in some ways, the Common Core was just the result of a broader movement in both math and ELA toward some really commonsense, consensus views of the best way to do things. And so in that sense, you can see some of that consensus even outside the Common Core.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)