School Gunmen Don’t Just ‘Snap,’ Says Author Who Urges Better Threat Assessment

In 74 Interview, author Mark Follman said shootings like the one in Uvalde, TX, can be prevented if schools seize on ‘the pathway to violence’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

See previous 74 Interviews: Parkland Teacher Jeff Foster on the power of protest; Superintendent Sandy Lewandowski on school shootings and mental illness; Parkland teacher, filmmaker talk HBO documentary on the shooting and its aftermath; and the full archive of 74 interviews.

The gunman in Tuesday’s deadly school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, was a lonely 18-year old who had all but dropped out of school, authorities said. Identified as Salvador Rolando Ramos, the gunman had a difficult home life, had been bullied since childhood over a speech impediment, and seemed obsessed with guns, classmates told The Washington Post.

Had he been on track to graduate, Ramos might have been one of many seniors from Uvalde High School to visit Robb Elementary School on Monday as part of senior week. Instead, authorities said, he barricaded himself into a classroom there on Tuesday and killed at least 19 children and two teachers before police shot him dead.

A new book suggests that a community-based violence prevention method has the potential to prevent mass shootings like the one in Uvalde.

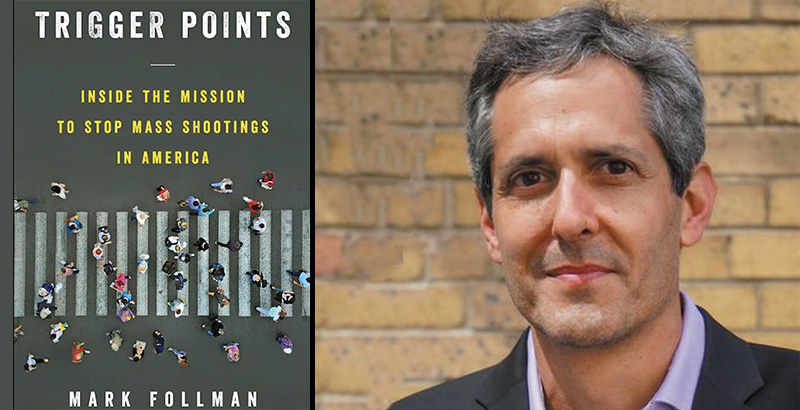

In Trigger Points: Inside the Mission to Stop Mass Shootings in America, journalist Mark Follman dives into emerging research on threat assessment, which brings together what he calls “a collaborative team of experts” in mental health, law enforcement, and, in school settings, education, to evaluate cases in which threats are made or in which witnesses become concerned that someone may commit “targeted violence.” The group intervenes to steer subjects away from violence and reintegrate them into the school’s social fabric.

The 74’s Greg Toppo spoke with Follman, who is national affairs editor at Mother Jones. The conversation, which took place just prior to Tuesday’s shooting in Uvalde, has been edited for length and clarity. Following Monday’s interview, the author responded with reactions to the carnage in Texas.

The 74: The details from Uvalde are still emerging and incomplete, but it’s clearly a horrible scene. Do you have any thoughts you’d like to share?

Mark Follman: It’s devastating to see this latest school massacre, not just as a journalist deeply invested in studying this problem but as a father of two myself. I grieve for these families in Texas along with the rest of America. I think it’s important to recognize that we can and must do better — including doing more in our communities to prevent planned violence of this kind. Early evidence in this case already indicates a trail of behavioral warning signs that may have presented opportunities to intervene.

Speaking of warning signs, your book focuses a lot on threat assessment. How is that different from profiling?

It’s really the opposite of profiling. Experts in this field of work learned long ago through research that there is no way to predict who will commit a mass shooting. There’s no such thing as a character profile of a mass shooter based on who they are or what their personal characteristics are: their background, race, ethnicity. What threat assessment does is study a behavioral process. It looks at the behaviors and circumstances leading up to school shootings or mass shootings, because these are planned attacks.

Like others in the threat assessment world, you say mass shooters “don’t just suddenly snap.” As you write, “They decide. They develop violent ideas, arm, and ready themselves, and then choose where and when to strike.” Can you say more?

That’s one of the big myths we have about this problem, that it’s impulsive. The idea that all shooters are crazy, that this can all be blamed on mental illness — that’s all wrong. In a basic sense, no mass shooter is mentally healthy. But the way that these attacks occur is through a process of planning, involving a complex set of factors, and there’s often a lot of rational thought involved. Extensive case research shows that mental illness is not fundamentally a cause of these attacks.

You write about “impulsive vs. predatory” violence. School shootings/shooters are the latter, right?

These are people who are planning over time. It is very much a process of behavior that builds, that escalates. The term that the field uses for this is “the pathway to violence,” and it describes that behavioral process. And that also is the opportunity for intervention, because it’s a period of time that is, in most cases, marked by observable warning behaviors.

About those behaviors: How can schools and communities get access to people’s intentions without attacking privacy and civil liberties? How can they prevent a school shooting without becoming the “pre-crime” unit described in Phillip K. Dick’s Minority Report?

A really important principle of this work is that it seeks to be constructive, not punitive. This isn’t trying to be a solution to this problem by criminalizing it, because in many cases, you’re talking about individuals who are raising concerns but haven’t committed any crime. And there’s no way to predict whether a person is going to commit a crime. That’s the stuff of dystopian science fiction: “Minority Report” and the like. Instead, what this is about really is looking at what, in many cases, especially in an education setting, are cries for help — young individuals who are in crisis, who may be suicidal, filled with rage, despairing, and they’ve developed an idea that they don’t have any other solution to their problems, and that this form of violence is the solution. It isn’t a matter of trying to criminalize that. It’s a matter of trying to step in and figure out what the root problems are and get them the help and support they need.

A lot of people might read that and say, “You can’t just offer a potential school shooter counseling and support and then march them back into third-period Algebra class.” The idea is that something else has to happen. It can’t just be reintegration — this is someone who might have shot up the school!

That’s a key point. Case management is an ongoing process, often over a longer period of time. And so a threat assessment team, in cases of serious concern, will continue to monitor and track closely an individual that is raising concern, not just to give them the help that they may need, but also, of course, to keep the school safe.

Where has this approach been successful and how?

The Salem-Keizer School District in Oregon built one of the first programs of this kind after Columbine, and they’ve continued to develop this work over the past two decades. They have a lot of institutional knowledge, and I was able to observe their team work cases for a lengthy period in 2019.

What does it look like?

I’m talking about a roomful of experts who meet once a week to go over their caseload — these are both new and ongoing cases. There is a lead school psychologist, security experts, social services, youth social services, and local law enforcement representation. And they’re all meeting and talking over these cases together. The team would spend a period of time discussing all of what they knew about the circumstances of a troubled kid, and continue to evaluate and update their plans for how to manage each case through constructive interventions. The cases evolve over time.

In the book, you write about a high school junior you call “Brandon.” Tell us about him.

He had made multiple threatening comments about bringing a gun and shooting up the school. And the latest comment prompted the team to take a serious look at his situation — because he was now getting more specific about what he planned to do, and that is often a red flag to threat assessment teams, as it suggests concrete action. It suggests a movement from conceptual thinking about violence toward actual plans to carry it out.

The team quickly gathered information by interviewing people around Brandon and learned some other things that were concerning, that he was starting to fail out of classes, and that he had quit drama club, which he had been very engaged with. Those are signs of personal deterioration that are concerning. There was a counselor on the team who was worried that Brandon was becoming suicidal, because of some things he was now saying that reflected very low self-esteem. Suicide risk is also an important factor in threat cases. There is a lot of case evidence showing a strong connection between suicidal and homicidal thinking. Many school shooters and mass shooters are suicidal. So with all of that taken together, the team had significant concern.

What did the team do with all this information?

They put together a plan to intervene intensively and quickly, extending Brandon support through counseling, through independent educational support, and by working to create stronger social connections for him within the school, specifically with two teachers that he was known to like, who could help try to improve his mood, to make him feel cared for and also help the team keep a close watch.

They also paid a visit to his home, right?

The Threat Assessment Team sent a school resource officer to Brandon’s home the day he made the threatening comments, which were reported by another student to faculty. So the SRO [School Resource Officer] goes out to his home to interview Brandon and his mom to determine whether or not he actually has access to a gun. Could he follow through on his threat to come back to the school two days later and commit a school shooting?

The SRO was able to determine that he did not have access to a weapon in the home. So that was important information in terms of imminent risk. And then the team continued to collect information about his case and develop a longer term management strategy. By fall 2019, with these measures to help him — through individual educational support, counseling, and other resources, including working with his mother to keep close tabs on his mood and his behavior as well — he improved and started doing better in school and he went on to graduate.

Speaking of guns: the reactions to Sandy Hook and Parkland in particular have shown that national gun control measures aren’t likely anytime soon. Do you see this failure as having an effect on how schools can combat the next shooter?

I decided to write a book about threat assessment because I came to see that it was a way forward on this problem that got past the gun debate. I came to see this method as an additional solution that’s potentially very powerful for addressing this problem, because gun violence of this nature — targeted, planned attacks — is very complex. And it requires, I think, a broader way of thinking about dealing with it. The debate over gun laws is vitally important and will continue to go on. But we also know that it’s very challenging territory in which to make progress. And I think community-based prevention, using the threat assessment model, is an additional way that we can contend with this problem. For the book, I was able to look inside a whole range of cases where it has been used successfully to thwart potential violence.

During the pandemic, we’ve seen a rise in mental health and discipline problems among young people. How might this affect schools’ risks and how can they respond? Do you expect targeted violence to rise short-term?

I think the good news here is that this approach is ultimately about early intervention. And as I was saying earlier, it relates very strongly to suicide risk assessment in kids. Suicide has also been a growing problem over the past decade. While the mental health crisis can be a very important factor in preventing potential planned violence, the work of threat assessment has broader potential benefits: because if you’re talking about trying to help kids in crisis, whether or not they’re planning violence, you’re still going to be extending that help.

The intensive team approach seems expensive. How can school districts afford it?

The method fundamentally is a community-based approach, meaning there are multiple stakeholders that share responsibility. It’s families, it’s the school system, it’s local law enforcement, it’s local mental health and social service agencies working together. So it’s not up to the school to do this themselves. But the school, of course, is a fundamentally important part of it. As to the question of resources, I asked a lot in my reporting for the book: “How do you scale this?” School systems are notoriously strapped for resources and time, and educators are overworked. And I think one of the more persuasive answers I’ve gotten is that this model seeks to use infrastructure that is already largely in place. The people who are going to participate on a threat assessment team in a school system already have these kinds of responsibilities and roles: the counselors, the administrators. And it’s a matter of getting them the training to do this work. It is still going to require some time and focus, but it’s not a matter of building this whole separate entity to do threat assessment.

What would you say to those who feel that a prevention model like this is simply too intrusive?

This work has to be done with respect to privacy and civil liberties. There needs to be oversight, and the leading teams I studied prioritize the need to build community engagement and trust in good outcomes, which can be a high bar. But what about the opposite: What happens when a school system doesn’t take a proactive approach like this? Look at cases where it was missing, that are tragic to the greatest possible degree. We saw this recently with the Oxford High School shooting last fall. That was a case where, in my view, in studying this work, there could have been prevention strategies that could have stopped that case from happening. There was a very long trail of glaring warning signs about the student that committed that attack, and that’s an avoidable event with this type of approach.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)