‘Provider of Last Resort’: Superintendent’s Last Plea for Help for Her Students

For years, Sandy Lewandowski told Minnesota lawmakers the unmet mental health needs of her district's kids had hit a tipping point. Then students died

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

On Feb. 1, Sandy Lewandowski got the call superintendents have nightmares about: There had been a shooting at a school. Intermediate District 287, where Lewandowski was in her last year before retirement, is a co-op made up of 11 districts in Minneapolis’ western suburbs. It exists to serve kids with unique disabilities, severe behavioral challenges and other needs that require specialized expertise.

For a decade before the shooting, in which a student died, Lewandowski had tried to draw attention to the deepening needs of her district’s children — and the increasingly dangerous conditions her staff worked in.

Students are sent to District 287 when their behavior, be it related to a disability or trauma, is more than their home districts are equipped to handle, or when their school lacks appropriate expertise to accommodate an intense need. This is both cost-effective and beneficial to students, who get specialized attention.

But it also makes District 287 what Lewandowski calls “the provider of last resort,” expected — with very little extra funding — to educate and treat kids who have been failed by both schools and mental health agencies. Unlike other districts, it cannot transfer out a student with a history of violence or a mental health condition that would normally merit residential treatment.

The one-two punch of the pandemic and the nearby murder of George Floyd by a police officer has accelerated the concentration of students with profound needs in the district. Over the last three years, the number of students with very aggressive and sexualized behaviors has almost doubled, there has been a 50% increase in children who are homeless or lack stable housing, and the number who require personalized instruction in class is increasing.

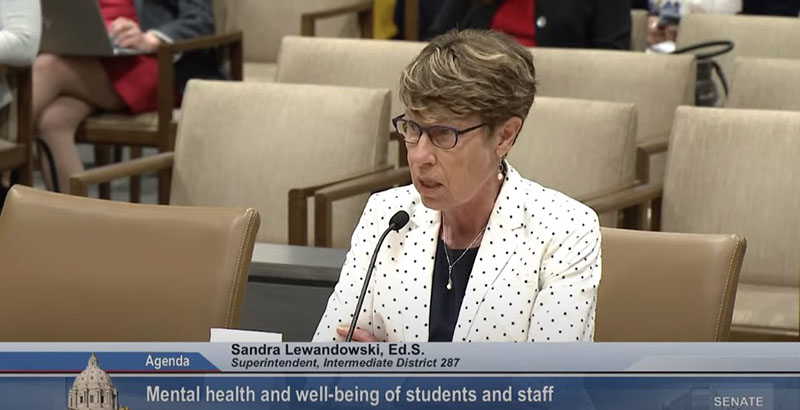

The day after the shooting, Gov. Tim Walz and Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan, a former Minneapolis School Board member, visited Lewandowski and her staff, pledging to “work with officials at all levels of government to seek needed change.” But the story disappeared in the news cycle. In May, with her retirement just weeks away, Lewandowski delivered blistering testimony before the Minnesota state Senate in hopes of securing $9 million to enable her to continue a successful in-school mental health program in her district and two similar ones nearby.

“Let me give you just a few examples from this year,” she told lawmakers:

“We had a teenager try to take their life by jumping off of a second-floor railing.”

“A teen who was homeless brought a loaded weapon to school early this fall. His mother had pleaded that he stay in the group home where he had lived and done well. But he was released and quickly became homeless.”

“One of our finest teachers was punched in the face by a young student, causing a concussion and injuries needing surgery. That teacher resigned.”

“A single mother called to express her displeasure with my decision to call a remote learning day because of bad weather. During the call, she tearfully told me that she was afraid to be home alone with her teenager.”

“A local police department wanted to come to our school to arrest a young teen on felony charges. They didn’t want to do it at his grandmother’s home, where he sometimes stayed, because Grandma feared for the safety of the young children in the home, and the grandson had access to weapons.”

“Finally, on Feb. 1, we became the first school in Minnesota to have a shooting that resulted in the death of a student since the Red Lake School Shooting in 2005.”

The 74’s Beth Hawkins wrote about 287 a decade ago, when Lewandowski, then on the job for eight years, first declared the district at “a tipping point.” She also happens to live down the street from the site of the shooting. What follows is an emotional exit interview, edited for length and clarity.

Walk me through the day of the shooting. What it was like to receive that call?

Momentarily overcome, Lewandowski takes a moment for tears to pass.

I didn’t know I was going to go there [break into tears]. Some days I do. Sometimes I don’t go there. But that’s what it feels like.

I had foot surgery about 2½ weeks before, and that day was trying to work from home. The call came from my assistant superintendent, who said, “Something terrible has happened, the police have taken over the building.” I had never heard anything like that. I knew it was something horrific.

I had to call my son to come and get me because I wasn’t able to drive. On the way, I talked to one of my other leaders who was in front of the building. He said, “Sandy, I’ve never seen anything like this. There’s so many emergency vehicles here. I can’t even explain it.” Even then, I couldn’t let my mind go to that worst possible scenario, even though I think inside I knew somebody had died.

When I got within a couple blocks of the school and saw the number of emergency vehicles around, I knew exactly what he meant: There were multiple police departments, the FBI, the ATF. Everybody had their own initials on their uniform. When I walked in, it proved my worst fears. At that point, something else took over. I just had to do the job.

You have been asking lawmakers for a way to pay for intensive mental health care services for your students for 10 years.

I have a thick folder I carry with me with multiple op-eds, testimonies, multiple letters to … three governors, commissioners of education, commissioners of human services. I was so explicit about what I thought would happen, because you can’t just keep having these very serious safety incidents over and over and think the odds aren’t going to catch up with you.

When I went into that Senate hearing room, I was as blunt as I could be. In my testimony, I included the fact that I had warned them multiple times that [without a permanent way to pay for students’ mental health care] something would happen. I added the fact that while I’m not a lawyer, I think this state could end up in litigation. If somebody took a hard look at our systems, what [officials] were told and what that resulted in ultimately — the situation we experienced on Feb. 1.

How do you think your testimony landed?

It got very, very quiet. In my experience, when you testify, and it gets very, very quiet, they’re listening. My best hope is that it landed in that moment. But I’m also a realist, and at the end of the [legislative] session, everything is on a furious pace. Whether their attention can be sustained over the next couple of weeks and, more importantly, over the next few years is very important.

I do believe we’re a canary in the coal mine. Things we experienced in our district this year are gigantic, because of the needs we see coming through our door. But there are other levels of need that are being experienced across all of K-12. Looking at what is underneath in terms of students’ mental health and need for racially appropriate school climates is going to be pretty important in coming years.

Help us understand how the social service safety net doesn’t help children before their needs compound to the point where they are referred to your school district.

There is no clear public policy guiding who provides children’s mental health services. We have private insurance paying for some people’s mental health care. We have the [state] Department of Human Services providing a substantial amount of Medicaid services. And then there’s been this growing funding of children’s mental health through the schools. But there’s not, to my knowledge, a clear, coherent public policy that identifies who should be paying for what and what our [respective] responsibilities are.

What I’ve seen as the years have gone by — certainly with the pandemic, the endemic and, for us, the school shooting — is that schools continue to be the provider of last resort, because that’s where the kids are. There’s a lot of entanglement of various pathways in children’s mental health.

The county has the ability to place a student, for example, in residential treatment. Or to provide intensive family services. What [the district] couldn’t ever successfully navigate is getting that to families in a timely and productive way, and in an alignment with the school. When we have a student who’s totally unraveling because of whatever’s happening with the trauma they’ve incurred, the mental health situation they’re in, we can’t wait for that all to play out. For us, the timeliness of the model is as important as the intensity.

So you built your own in-school system.

We got the best professionals in the room and said, if money weren’t an object, what would high-quality services look like? We determined it would be a therapeutic teaching model, for our elementary students particularly, that would include a full-time mental health clinician in the classroom with the full-time classroom teacher. There would be a full-time family therapist who would work exclusively with families. And there would be what we call a systems navigator, who would understand that families often are met with many challenges, whether it’s homelessness, or court appearances, or poverty, and would help address those things by helping families find the services.

Our special education teachers need to do what they’re trained to do. And a clinical mental health trauma expert, if you will, needs to be in there at the same time to do what they’re trained to do. And the family needs pretty intensive support services to change patterns, in order for the student and the whole family unit to become healthier.

The only alternative for some of the students that are currently in the [therapeutic teaching] model that’s somewhat equal in terms of intensity is a residential treatment model. But there’s just not treatment beds. Kids are being boarded in emergency rooms — and we can’t even get many kids into the ER. There really isn’t much choice for the population of students that we serve.

During the unrest in the Twin Cities that followed George Floyd’s murder by a police officer, my daughter and I watched your students create protest art at one of your schools, which is down the street from our house. It is also the school where your students were killed. The art is still up, which seems symbolic to me.

We aren’t anywhere close to reconciling all of that. The inequities our children and their families have experienced have resulted in trauma and poverty that are at the roots of their needs today. A lack of mental health services is one of the major inequities. We haven’t gotten anywhere near that conversation.

The work that we’ve done in the area of race in the last two years has pressed me to re-examine my own values and actions as a white woman over and over. But I’m proud that as a district we probably pushed to reset on equity as hard as any district could push. It is very hard work, and needs to go so much further.

Our current director of race and equity, Radious Guess, brought us a racial equity analysis tool. When we’re making decisions, we ask ourselves three or four questions that help us isolate race. Questions like, who will be burdened by this decision?

For the first year, I would just breeze right by until somebody would say, “Can we enact the racial equity analysis tool?” That process alone has slowed us down to better identify what’s going on in the decisions we are making. I’ll give you an example that’s front and center right now. I made a decision just about a year ago to remove the last metal detectors in our schools, because all the evidence says they disproportionately impact BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and people of color] students in a negative way.

Now, this year, we have one school shooting and two weapons incidents — one [in April], a fully loaded gun in one of our buildings. People are terrified, I’m terrified. You cannot have loaded weapons in any school building where we have very common, reactive, impulsive behavior going on.

After the shooting, we created a safety response committee to make recommendations. It won’t surprise you that bringing back metal detectors tops the list. Well, the evidence is still the same. And now I have an overwhelming response to put metal detectors back in buildings. That’s not been decided yet. It’s very complicated because our BIPOC staff and families are saying the same thing: Bring back metal detectors.

We moved [police officers providing security] out of our buildings a few years ago and went to what we call a safety coach model. [At the time of the shooting], our safety coaches responded immediately — obviously, they were on the scene. And were very effective. Some of our former students are now education support professionals in our building, and at least one of them was first on the scene as well. All of them worked very well with the formal response by all the [law enforcement] agencies. I’ve not heard one person criticize anything of those first responders. I’m grateful that worked as well as it possibly could in those very dire circumstances.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)