Increasing Segregation of Latino Students Hinders Academic Performance and Could Amplify COVID Learning Loss, Study Finds

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Elementary students from low-income families are less likely than they were two decades ago to attend schools with middle-class peers — a trend tied to the growth of the Latino population and continuing “white flight” from many school districts, a new study finds.

Conducted by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Maryland, the analysis of over 14,000 districts nationwide shows that in 2000, the average child from a poor family went to an elementary school where almost half of the students were defined as middle class. By 2015, that figure had fallen to 36 percent.

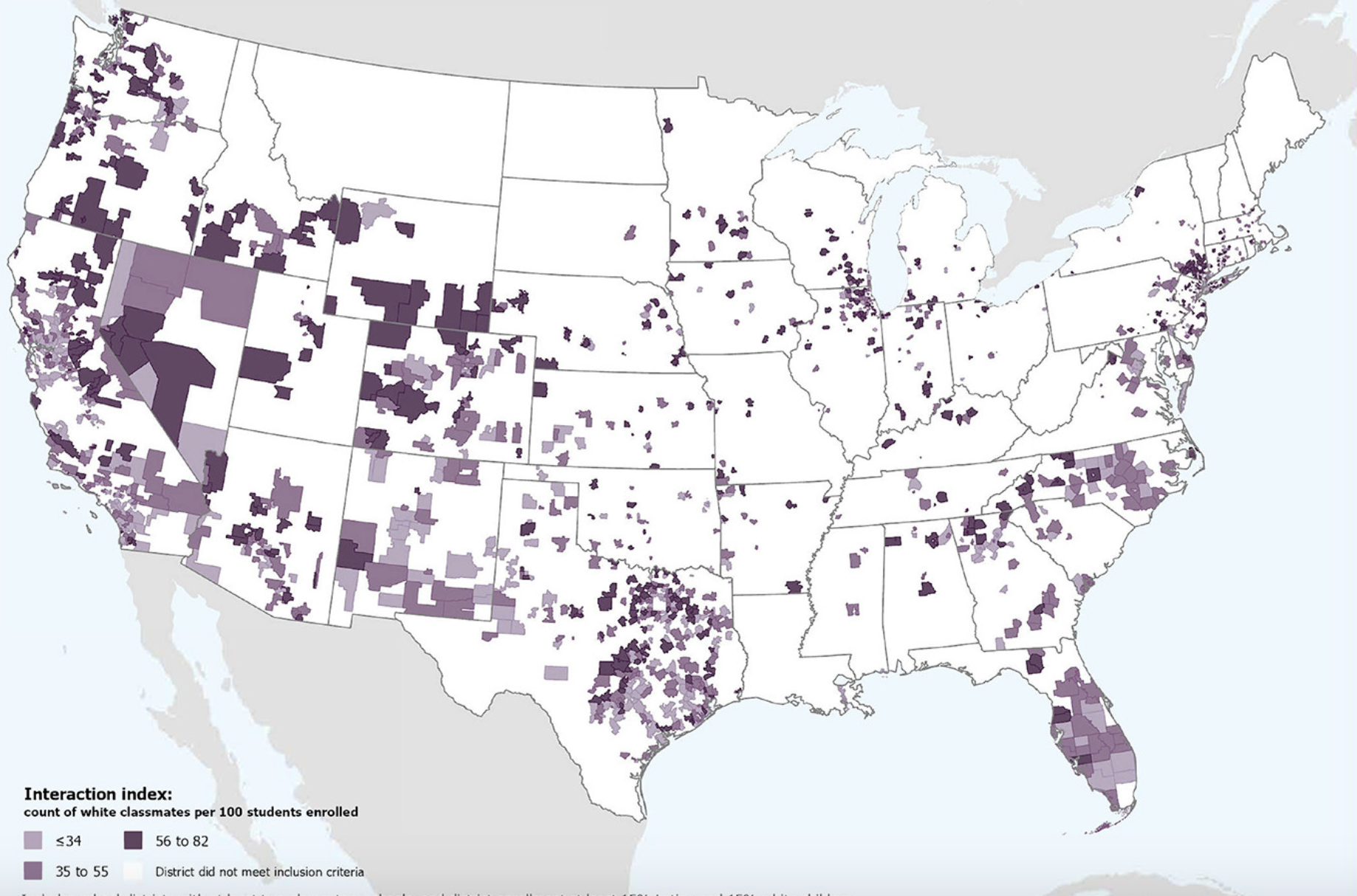

As the nation’s Latino student population grows, the shift — especially in the West and the South —means they are less likely to experience the benefits of racially and socioeconomically mixed schools, the study notes, including higher test scores, smaller racial achievement gaps and higher college enrollment rates.

The findings, according to the researchers, also carry broad implications for academic recovery efforts in the wake of the pandemic.

A previous analysis by The 74 showed disproportionate increases in chronic absenteeism among English learners, three-fourths of whom are Spanish-speakers. And data shows that Latino families were among those hardest hit by COVID-related job loss and financial hardship, creating a larger challenge for schools serving high concentrations of Latino students.

“Deeper forces have sustained achievement disparities in recent decades, especially this worsening isolation of the poor from middle-class students,” said Bruce Fuller, a Berkeley sociology professor and lead author of the paper. “COVID-era learning loss is but a surface symptom of deeper ills that beset public education.”

Backlash to busing “slowed desegregation efforts” in districts with large Black student populations and shifted attention toward improving schools in Black and Latino communities, the authors said.

Now higher birth rates among Latinos, combined with the movement of Latino families to the suburbs, have contributed to racial isolation, they wrote.

“‘White flight’ from the public school system translates into resource flight from racially isolated schools,” said Feliza Oritz-Licon, chief policy and advocacy officer at Latinos for Education, a nonprofit focusing on teacher recruitment and education policy. She added that in racially isolated schools it becomes easy to “dismiss” Latino students as underperforming.

But not all districts have seen a decline in their white student populations. The chances that Latino children will interact with white peers at school are higher in the Midwest and Northeast. In fact, the researchers found 800 school districts where the white student population had not declined over that 15-year time period, even as the Latino student population grew.

‘Under one school roof’

The Berkeley study builds on research by Sean Reardon at Stanford University, whose work drew connections between racial segregation and large achievement gaps due to concentrations of Black and Latino students in high-poverty schools.

Pedro Noguera, dean of education at the University of Southern California, said rising segregation not only affects who students sit next to in class, but also broader support for public schools.

“All of this is troubling. We have to get better at offering the kinds of programs that will attract affluent parents,” he said, noting that International Baccalaureate programs, Advanced Placement courses and other offerings “send the signal of a high standard. That’s what Latino parents want as well.”

Fuller and his co-authors wrote that without more inter-district choice programs, which would allow entree to higher-performing schools in wealthier neighborhoods, Latino students will continue to have fewer opportunities to attend integrated schools.

A report released last year by Bellwether Education Partners explored additional obstacles to integration created by a lack of affordable housing in districts with higher performing schools; even if low-income families want to move into such school districts, housing options are scarce.

“Civic leaders and educators must expand ways of pulling the nation’s diverse children under one school roof,” Fuller said.

In 2020, the Century Foundation, a left leaning think tank, identified over 900 initiatives underway in school districts and charter school networks to increase integration. Some of the programs were voluntary, while others resulted from desegregation orders.

‘The country’s prosperity’

But Noguera said some charter schools predominantly serve Black students or Latino students, contributing to segregation.

By 2060, Latinos are projected to make up over one fourth of the U.S. population, according to Census Bureau estimates, and Latino children currently account for a quarter of public school enrollment.

Increasing the numbers of Latino educators is one way for districts to increase achievement, researchers at the Brookings Institution wrote in a paper last year that focused on the Clark County School District in Nevada. They cited studies showing that Latino students are more likely to be placed in gifted programs and take Advanced Placement courses when their schools have more teachers that look like them.

Recruiting more Latino educators and giving Latinos a greater role in education policy is also a priority for philanthropist McKenzie Scott, who last week donated $5 million to Latinos for Education to support the organization’s work.

Latino educators are often assigned to high-need, racially isolated schools because they reflect the cultural backgrounds of students. But turnover is high, with many leaving the profession within four years, noted Oritz-Licon of Latinos for Education.

The organization’s October report featured concerns from Latino educators, such as the cost of earning a degree and requests from administrators to provide translation services without additional compensation.

Oritz-Licon called on schools serving Latino students to use relief funds for afterschool programs, academic support and parent engagement efforts since many high-needs schools might lack those services.

“Latino students are American students,” she said. “Their educational outcomes should matter because as a growing population, their prosperity is the country’s prosperity.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)