‘Drawing Better Lines’: The High Cost of Housing Even a Neighborhood Away Prices Many Low-Income Families Out of Better Schools, Report Says

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The Laraway Community Consolidated School District, west of Chicago, has an ample supply of housing where a family at the poverty line can find an apartment for about $1,000 per month.

But if the family wants to move their child to better schools in the nearby Elwood, Union or Manhattan districts they would be hard-pressed to find housing in that price range.

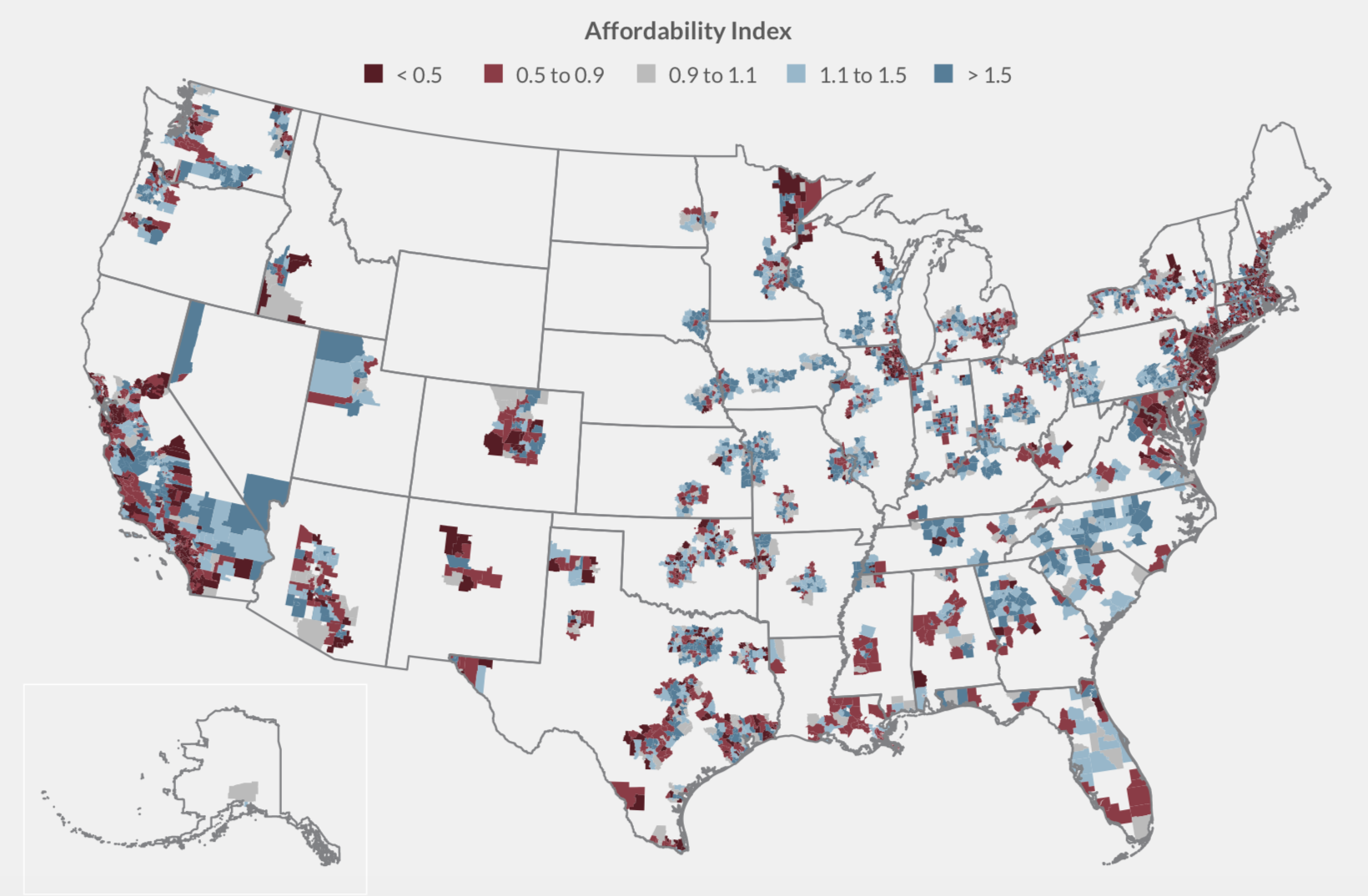

These invisible boundaries are what researchers at Bellwether Education Partners call “border barriers” — lines between districts that frequently keep low-income families out of higher-quality schools. The Chicago area, the authors write, has 45 such divisions, where families in low-income housing brush up against districts with more resources and better schools but few, if any, affordable rental units.

Bellwether explores these differences in “Priced Out of Public Schools,” a report released last week that adds a new layer to our understanding of how closely housing and education are intertwined. Districts with out-of-reach rental prices spend, on average, at least $4,600 more per student — the result of higher property taxes. While states’ school finance formulas aim to equalize funding across districts, they don’t make up the gap.

“As we think about what we need to do moving forward, it’s not just an education solution alone,” said Alex Spurrier, co-author of the report and a senior analyst at Bellwether Education Partners, an education think tank. States, he said, should consider multiple policy levers to address “what is a very thorny challenge.”

The report comes as rental prices continue to rise and many low-income families face evictions, long delays for federal rental assistance funds and landlords who reject housing vouchers. When families relocate to more affordable housing, their children often must leave not only their schools, but their districts as well — especially in states like Texas, California and Illinois, where metro area maps are dotted with dozens of small school districts. The authors label the phenomenon “educational gerrymandering,” the creation of smaller, exclusive districts that cater to higher-income, less racially diverse student populations. While the report recommends multiple approaches to address the disparities, experts note that altering district boundaries is politically risky: People with money are likely to vote against those who meddle too much.

“People who have wealth are willing to use it to get high-quality schools.” said Nat Malkus, a senior fellow and the deputy director of education policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “The rules of the game do produce some inequities.”

Mergers and secessions

Some of those rules date back to nearly a century ago when the nation entered a school consolidation movement that by 1970 had cut more than 100,000 districts down to less than 20,000. Now there are 13,000.

But district mergers tended to lack high-minded ambitions to create more racial or socioeconomically balanced schools. Rather, they were likely to be unions of districts with similar demographics, explained Tomas Monarrez, a research associate at the Urban Institute who has studied racial and ethnic segregation in schools.

Some of the starkest examples of drawing boundaries to benefit wealthier populations include recent efforts by some communities to break away from larger, often county-level, school districts. “Fractured,” the 2017 report from EdBuild, noted 73 secessions since 2000, with another 55 either attempted or in progress.

Several have launched in the Northeast, but the Bellwether report also includes examples in the South. In Memphis, Tennessee, for example, communities within Shelby County split off into smaller districts in 2014 after the majority Black Memphis district dissolved and merged into the county district. In Alabama, there have been 10 successful attempts since 2000, with more in the works.

“At the very least, we should be wary of those secession trends,” Monarrez said. Mergers, however, can minimize disparities in access to quality schools if leaders pursue them with the goal of improving equity, he said.

Some states have created programs where multiple districts share tax revenue or allow students to transfer into schools across district lines as a way to reduce disparities. The Nebraska legislature created such a plan involving 11 Omaha-area districts. In Massachusetts, the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, encompassing Boston and the surrounding area, is another example.

But Malkus, at the American Enterprise Institute, cautioned that such options only tend to “nibble around the margins.” Daniel Thatcher, a senior fellow at the National Conference of State Legislatures, noted that open enrollment programs can make school funding disparities worse because the receiving district gets the state funding for those students.

School choice programs are another way to allow students to attend a school outside their neighborhood, the authors suggest. The results of that approach are mixed. Monarrez found that within a district, charters lead to a slight decrease in student diversity. But across a metro area, the presence of charters can create schools that are more racially mixed.

That’s what leaders in School District 49, adjacent to the Colorado Springs, Colorado, district have found. The district is considered “inaccessible” to lower-income families because there’s not enough affordable housing to meet the demand, according to the Bellwether report. But more than a third of the district’s students come from outside the district for traditional, charter and online options, said Peter Hilts, the system’s chief education officer. Half of the Colorado Springs district’s students are nonwhite, compared to 43 percent in District 49.

“There’s no question that open, inclusive choice has made us a more diverse district,” Hilts said. “If you genuinely want educational equity, you must believe in school choice, and if you truly advocate for inclusive choice, you must address other factors like transportation, affordable housing, and childcare options that can inhibit choice.”

Housing affordability not only affects families wishing to move into a district, but also those who want to stay put. In Tacoma, Washington, low-income families are beginning to leave because of a lack of housing options, said Elliott Barnett, a senior planner for the city. Proximity to quality schools is a key element of Home in Tacoma, a project that recommends building additional types of housing in neighborhoods that were previously reserved for single-family homes.

“We know that where a person lives has a link to their access to opportunities that have a big impact on our lives such as education achievement, income, life expectancy and others.” Barnett said. “Even if kids can travel from elsewhere to a high-performing school outside their neighborhood, that is another burden to overcome.”

Some states, like Oregon and California, have recently passed legislation to increase the supply of affordable housing. While such efforts haven’t always taken school locations into account, Monarrez said that’s beginning to change. California governor Gavin Newsom mentioned the need for a wider array of housing options near schools as one goal of his state’s legislation.

The next step, Monarrez said, is for policymakers to reconsider district boundaries as well.

“We need to find out more about what would happen if we changed these lines,” he said. “A viable solution is drawing better lines.”

Disclosure: Andy Rotherham co-founded Bellwether Education Partners. He sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)