Black, Latino Students Disproportionately Taught by Inexperienced, Uncertified Teachers, New Research Shows

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Black and Latino students nationwide are disproportionately learning from inexperienced and uncertified teachers, according to new research.

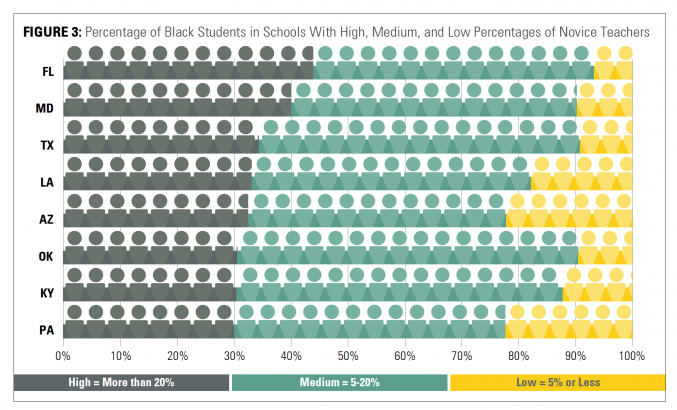

Across the country, schools serving predominantly Black students have 5 percent more novice teachers than schools with fewer Black students, according to analysis from education advocacy nonprofit The Education Trust.

In a quarter of states, gaps are even wider: Predominantly Black schools have at least twice as many novice teachers as schools serving the fewest.

In two particularly egregious cases, researchers found in Mississippi, a quarter of Black students attended schools with high percentages of novice teachers, compared to just 7 percent of non-Black students. And in Louisiana, one in three Black students attend schools with high percentages of inexperienced teachers.

“Our findings reveal that our education system is failing Black students, as they find themselves more likely than any other group of students to be in classrooms with teachers who are in their first years of teaching or teachers who are uncertified,” the two reports, focused on Black and Latino students separately, stated.

Little progress in efforts to retain teachers in these schools has been made since federal data showed similar disparities in 2014 — so stark then that the Department of Education began requiring states to outline teacher equity plans.

Novice teachers said they leave their posts because they receive little training or mentoring. As a result, students could go years without an experienced educator — the primary predictor of student success.

Gaps in access to quality teachers can have long-term consequences on students’ academic achievement, college enrollment and future income.

Without action, the churn of inexperienced teachers will have long-term, negative impacts on students of color at a rate not experienced by their peers in predominantly white schools, Education Trust researchers said.

“…The pattern of Black and Latino students getting assigned to brand new teachers year after year after year — attending schools with a majority of teachers who haven’t had the time to master their craft and need more support — is at its heart a racial justice issue,” said Sarah Mehrotra, who co-authored the two reports.

“If we care about equity in education, we have to pay attention to who is teaching our Black and Brown students, and what we can be doing differently to support them,” she said.

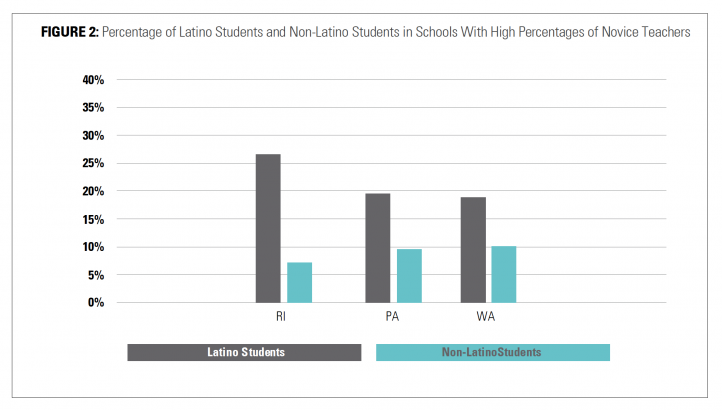

In 32 states, there are more first-year teachers in schools serving the most Latino students. Three – Rhode Island, Pennsylvania and Washington – have the biggest gaps, with Latino students at least twice as likely to have a novice teacher.

In Massachusetts, access to certified teachers is particularly inequitable: 29 percent of Latino students attend schools with high percentages of uncertified teachers, compared to just 12 percent of their peers.

The findings bring states’ commitment to teacher development into question at a time when many face educator shortages and allocate billions in pandemic relief aid to accelerate learning.

“This disparity… means that groups of students are missing out, by no fault of their own, on the critical learning opportunities necessary to prepare them for success in college and/or the workforce,” the reports stated, analyzing the U.S. Department of Education’s 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection.

In the predominantly Black and Latino schools analyzed, where there are fewer experienced educators, teachers of color are “over-represented” and have higher turnover rates than their peers — a “disruption” for students and communities, Mehrotra said.

Teachers of color experience “antagonistic school culture, [are] deprived of agency/autonomy, navigating unfavorable working conditions and carrying an “invisible tax” – the extra work they take on (being a translator for families, being a disciplinarian) without additional compensation,” she added. Vacancies are filled by substitutes or novice teachers.

One New Orleans teacher told the Education Trust: “The teaching profession was built on altruism, and many folks have taken advantage of this to bring in teachers on lower salaries.”

Though 2020-21 data is not available, Mehrotra predicted schools serving predominantly low-income students and students of color, where teachers double as counselors or manage larger classes, “are bearing the brunt of these pandemic related exits, teacher burnout and these alarming shortages.”

Stronger statewide data systems — to track teacher departures, demographic data and professional development opportunities — tops the reports’ policy recommendations to retain experienced teachers for students of color.

Researchers say while there are bright spots like Colorado — where new teachers enter a three-year mentorship program and can access loan forgiveness for working in high-needs schools — the problem and its solutions have been widespread and well-known.

“We could have predicted the data in a lot of ways,” Education Trust researcher Eric Duncan said, adding the gaps have persisted for years. States and districts must double down on their commitment to engage teachers directly to, “go a little bit more under the hood and say, Why is this happening?”

Further recommendations from the reports include investing in mentorship, residency and grow-your-own programs; incentivizing work in high-need schools and subjects; and hiring earlier in high-turnover districts.

Disclosure: Marianna McMurdock was an intern at the Education Trust-West in the summer of 2020.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)