San Fran Ballot Measure Reflects 10-Year Battle to Reinstate 8th-Grade Algebra

Vote is largely symbolic after school board already agreed to restore it, but districts nationwide are still grappling with when to offer algebra.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The San Francisco Unified School District, which pulled algebra from its middle schools 10 years ago in the name of equity, will bring the course back next fall, ending a controversial experiment that some say squandered the opportunity for advanced learners to excel in mathematics — and did little to close the achievement gap.

The public will vote on the issue in a ballot measure tomorrow, though the effort is now largely symbolic: The school board, facing consistent pressure to reinstate the course, opted to restore it during its Feb. 13 meeting.

“After 10 years of damage, the district did the right thing,” said Rex Ridgeway, who, along with several others, filed a lawsuit against SFUSD on the matter last year, casting doubt on the gains the district said it made by removing the course from middle school.

San Francisco is just one of many school systems nationwide that has grappled with when to offer algebra in a battle that has pitted equity against rigor. An earlier survey by The 74 of the country’s largest school districts showed varied participation rates in the course at the middle school level with white and wealthier students often having greater access.

Some education experts called algebra an unnecessary barrier to student success while others were trying to increase the number of children who can take it.

Dallas made advanced coursework at the middle school level, including mathematics, opt-out rather than opt-in, dramatically increasing participation rates among traditionally marginalized students — without seeing a drop in scores. Cambridge Public Schools, which nixed middle school algebra years ago, recently reversed itself after parents pushed back.

While some groups, including the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, praised San Francisco for its earlier decision to remove the course, parents quickly mobilized against it. They feared the plan would hinder students’ ability to take calculus in 12th grade. The impact, they reasoned, could follow them to college, jeopardizing their chance to enter lucrative STEM fields.

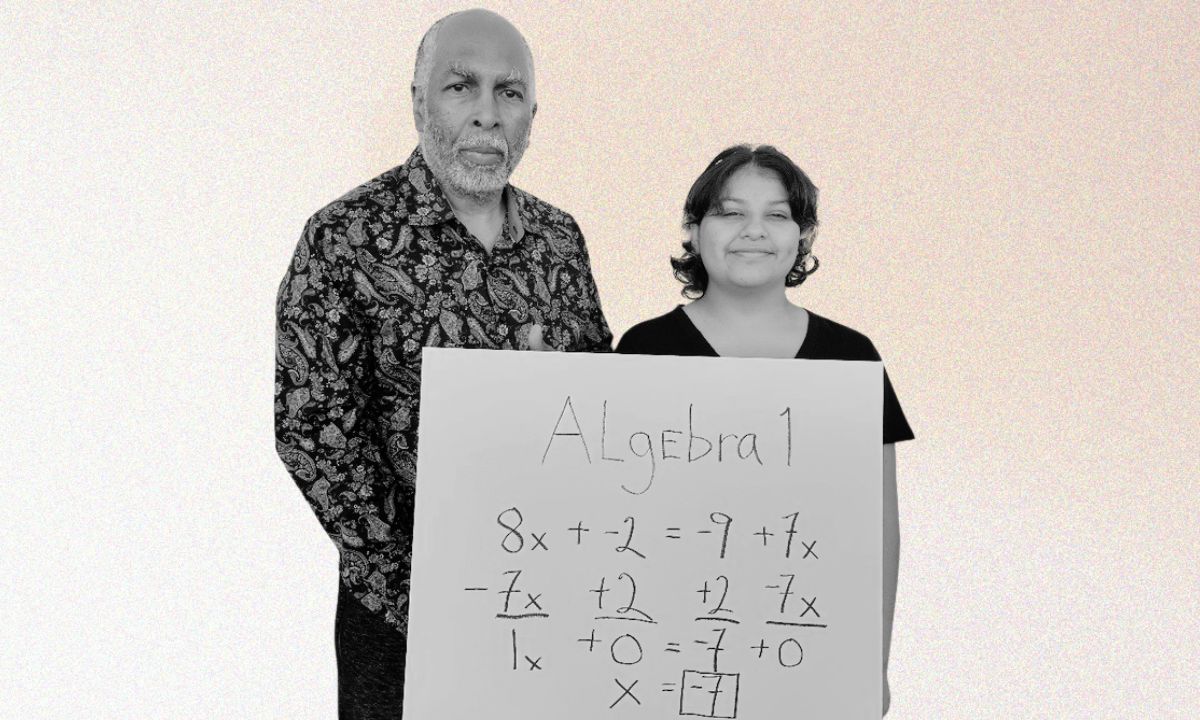

Ridgeway, a retired stockbroker, tutored his granddaughter, Joselyn Marroquin, from first to ninth grade, plugging in what he described as gaping holes in math, English and science instruction.

“Immediately, I saw she was not getting the type of education I would expect,” he said.

Ridgeway paid $860 for Marroquin, now 16, to take an online algebra course the summer before her freshman year of high school so she could sail through the class in 9th grade — and double up on another course, geometry.

But it was a challenge.

“It was a little difficult because it was online,” Marroquin told The 74. “I think I learn best in person.”

She said the course succeeded in preparing her for high school math, but that the time commitment ate into her other plans.

“Although classes were in the morning, I had to complete homework and study for the next lesson,” she said. “Because of that, it was difficult to do other activities I enjoyed. I didn’t really have a summer vacation.”

SFUSD moved to its current model to address the fact that few students were successfully progressing through its math sequence at the time: Just 19% of tenth graders — and only 1% percent of Black children — had passed the state math assessment and had not repeated math coursework across the 2011-12 and 2012-13 school years.

Those pushing for the change also noted a lack of participation in advanced math courses among Black and Hispanic students.

But a 2023 Stanford study found “large ethnoracial gaps in (Advanced Placement) math course-taking did not decrease after the policy change.” Specifically, the percentage of Black students enrolling in any AP math course in high school remained the same while Hispanic student participation increased by just 1 percentage point.

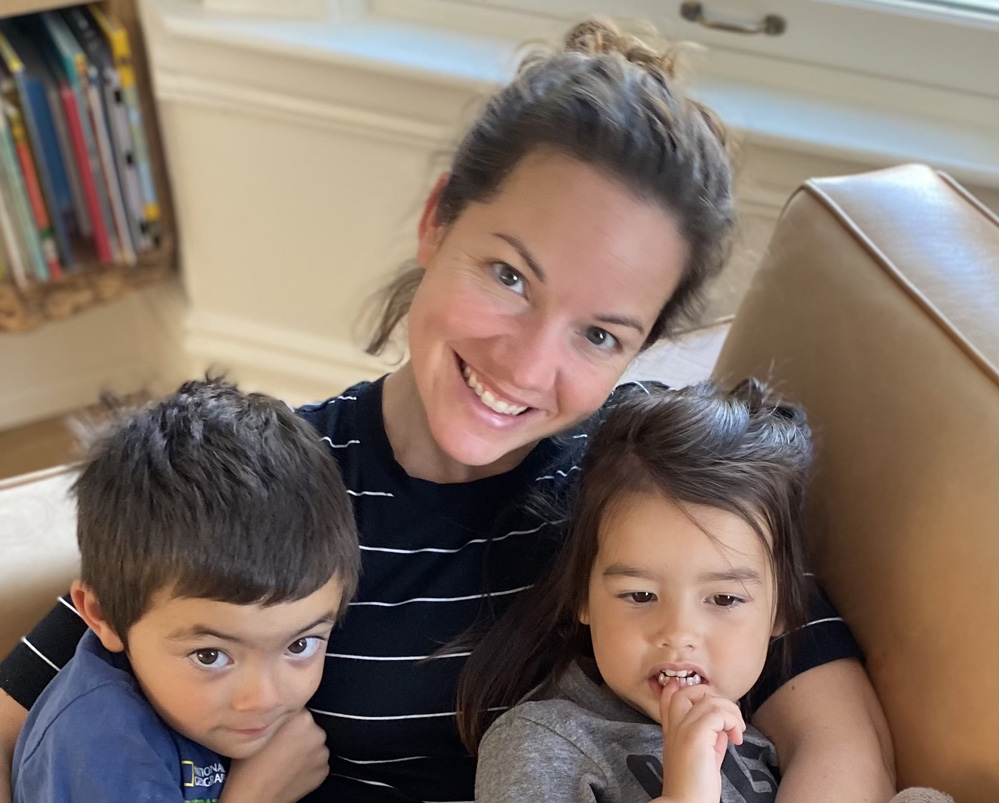

Meredith Dodson, executive director of SF Parents, understands the school district’s rationale for eliminating the course, but has long disagreed with the move.

“I think their experiment 10 years ago to delay algebra was well-intentioned, but in the end it had the opposite of the intended effect,” she said. “Kids who were supposed to be helped by that policy change were ultimately further harmed.”

Dodson said the disparity is stark.

“Parents around San Francisco are shocked when they hear algebra isn’t offered in middle school currently,” she said. “It’s time to bring it back, and we’re just glad that the district isn’t ignoring the data any longer.”

California public schools, like those in many other states, have lost tens of thousands of children to private schools and homeschooling post-pandemic. SFUSD’s student population alone shrank from 58,018 in 2014 to 2015 to 49,560 in 2023-24. District leaders just announced they will shutter some schools because of the loss.

The district’s reversal on algebra comes two years after three school board members were recalled in a February 2022 referendum. The vote reflected the public’s enormous dissatisfaction with school closures, the renaming of campuses and changes to admissions at a competitive high school.

Algebra will be piloted in several forms in the district next fall. It will also offer an online Algebra 1 course next school year and a summer course in 2025.

Patrick Wolff, cofounder of Families for San Francisco, served as the group’s executive director before the organization was absorbed into TogetherSF. Wolff, who had children in the district from 2010 to 2022, said its problems extended well beyond a single course.

“SFUSD has done a terrible job of teaching kids math,” he said. “Kids who are capable of learning more math have been held back for no good reason and kids who need more support in order to reach their full potential have absolutely been failed in receiving the support and instruction they need.”

Wolff said there is nothing wrong with acknowledging that some students might excel in advanced mathematics at a younger age while others will not — as long as those who struggle are helped to improve.

Melodie Baker, national policy director at Just Equations, an organization that promotes math policies that support equity in college readiness and success, said the district can’t simply return to an earlier, failed approach.

“So the prior tracking policy didn’t lead to equitable outcomes,” she said. “Detracking didn’t lead to equitable outcomes either. So it makes sense that they’re not sticking with it, but they’ll need to find new ways to implement eighth-grade algebra that ensure better outcomes for Black and Latinx students. Not just revert to what they were doing before.”

A RAND study released last month noted just 65% of U.S. principals said their elementary or middle school offered algebra in eighth grade — but only for some students. Twenty percent of respondents said it was open to all.

Eighth-grade algebra was even scarcer in California: only 48% of principals said their school offered the course, and only to certain children. Eighteen percent said any child could enroll.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)