Reading Supports Abound in Schools, But Effective Math Help Much Harder to Find

When it comes to math, there’s less of everything: nearly 50% of schools employ trained reading specialists, while only 23% have math specialists.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Correction appended

When Cindy Apple began as a special education teacher at Broadmoor 3-5 Elementary School, in Louisburg, Kansas, more than 20 years ago, students needing help in math were assigned to “pull-out groups,” often at the end of math class. Busy teachers handed students off to aides, who slowed the lesson down, reworking the same problems again.

The help was scattershot and often not delivered by trained teachers, and students struggled to improve. “They were taking students through the motions of the assignment again,” Apple said. “But we weren’t really working on the missing skills.”

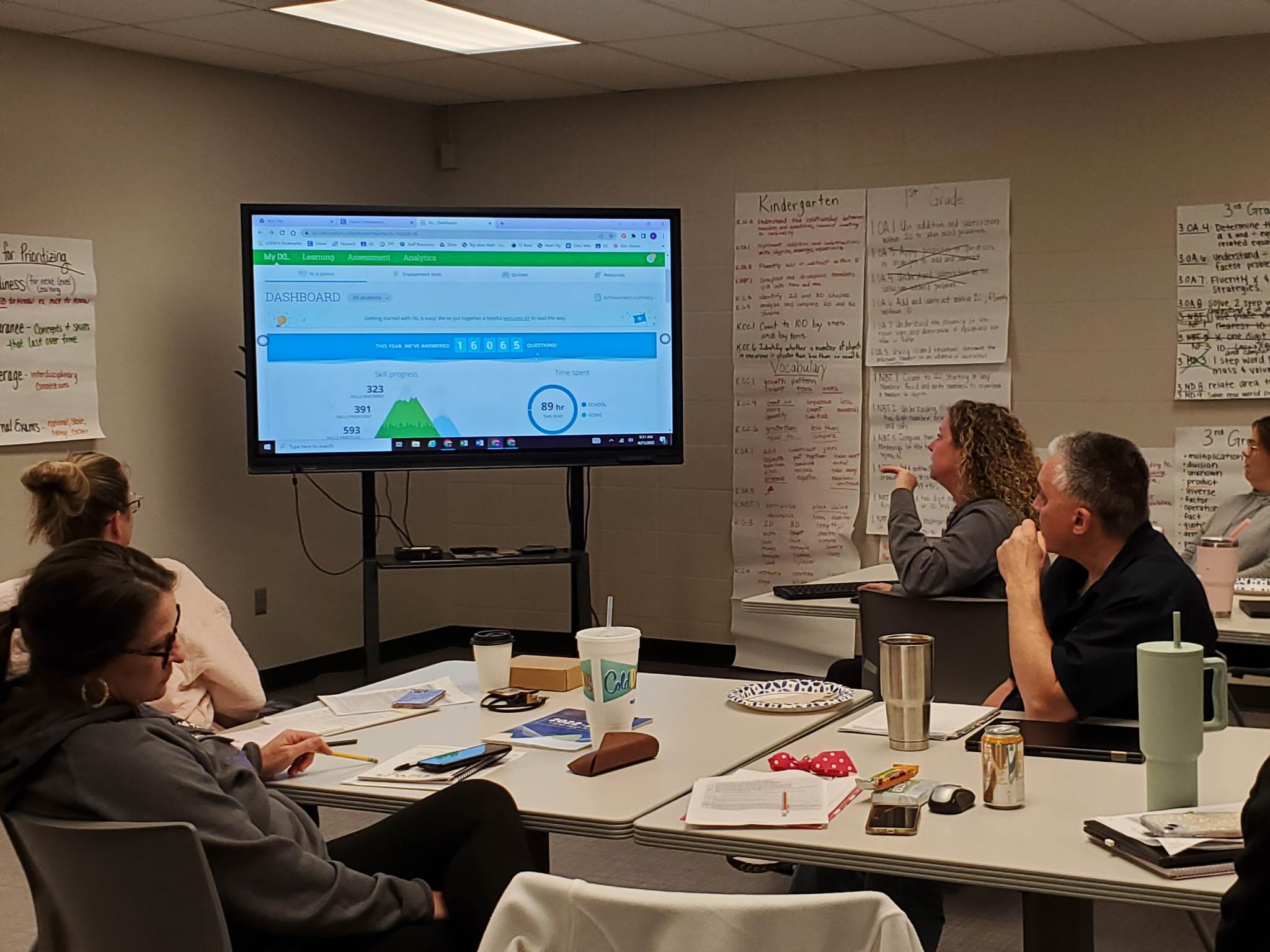

Then in 2018, the same year that Apple became principal at Broadmoor, she took the Kansas statewide infrastructure for supporting students in reading and math and made it a top priority. Grounded in evidence, the system used student testing data to target missing skills and inform what kind and how much help students needed, ranging in intensity from whole-class instruction to personalized, targeted tutoring.

Apple used the new framework to take a hard look at their entire system and rework how math was being taught: the standards, the curriculum and how the school was handling help for struggling students. “We homed in and got very specific in a very organized way,” Apple said.

Since the support system has been in place, student test scores across the grades have improved. In 2019 for example, 60% of third-grade students passed the state test; this spring, it was 80%. Fourth and fifth grades have had similar improvement.

Broadmore’s organized, systematic approach to helping students in math is far from the norm. While the majority of schools across the nation have organized approaches in place to address student problems in reading, far fewer offer the same help for math.

Lack of math help often starts with the states. A majority don’t require schools to provide support for students who struggle in math—recent reporting by Education Week showed that while 32 states require schools to provide teacher training, evidence-based curricula and support plans for reading, only seven states have similar laws on the books for math.

Districts that have adopted multi-level frameworks for helping struggling students — such as Multi-Tiered Systems of Support or Response to Intervention — are more likely to have implemented it for reading than for math. Studies from a decade ago show that 70% of districts had multi-level frameworks in reading for elementary schools, while only 47% had math frameworks. A recent review conducted by associate professor Sarah Powell at the University of Texas, Austin, found that not much has changed. In her not-yet-published survey, she found that districts had more ways to identify students, more support personnel and more interventions dedicated to reading.

“It is typical that most schools screen students in reading and have pretty good intervention systems set up in reading, but that isn’t the case in math,” Powell said.

Math often gets less of everything in schools

Recent national and international tests have revealed unprecedented declines in student math scores brought on, in part, by the pandemic. Experts and Education Secretary Miguel Cardona have called for more attention to be paid to math instruction. But some teachers say the current science of reading movement, whose phonics-focused method of instruction swept through classrooms, has dominated discussions of student improvement.

An instructional coach at an Iowa elementary school said her school has devoted serious resources over the last several years to revamping how they helped struggling readers — a large portion of their low-income, English-learner population — get on track. But there wasn’t the same push for math.

At least half of students in each grade have been flagged as needing intensive help in math — but they aren’t getting it. “We don’t have enough resources to do that same thing in math,” said the teacher, who asked not to be named because she feared repercussions at work. “This year, we have no one assigned to math intervention in most grades. We are creatively using some English language teachers [as math specialists], but we lack that front-line instruction.” Her experiences were echoed by multiple other teachers interviewed for this article who did not want to be quoted.

Most of the nation’s students are struggling in math. Math disabilities, which are present in about 7% of the student population, get much less attention than reading disabilities, and often go undiagnosed. Meanwhile, students may not have a disability but are still working below grade level.

Sixty-five percent of fourth graders scored either “below basic” or “basic” in math on the most recent NAEP test, and nearly three-quarters of eighth graders scored the same, meaning a majority of students possess only a partial mastery of math’s fundamental knowledge and skills needed to achieve proficiency and college readiness.

Reading is often schools’ top priority. But math proficiency is crucial, too, experts say. It predicts overall academic achievement and college readiness, shapes higher career aspirations and perhaps even higher future earnings — not to mention a pathway to lucrative STEM careers.

“In the early grades, the dominant focus for intervention is on reading. There’s a general belief that reading is more important than math,” said Lynn Fuchs, professor emerita of special education, psychology and human development at Vanderbilt University. “But in today’s workplace and everyday life, to be successful in terms of your occupation, your earnings are going to be greater if you not only read well, but are also proficient in math.”

But experts say when it comes to supporting math students in schools, there’s often less to work with: a smaller body of scientific evidence on exactly how to help students who struggle than in reading; less teacher training; fewer evidence-based skills assessments and interventions for students; and even less confidence and knowledge among teachers, especially elementary teachers, who feel prepared to teach it.

New teachers often arrive at school less prepared to teach math compared to reading. A 2022 report from the National Council on Teacher Quality highlights how teacher prep programs have beefed up their math instruction over the last decade, but most still have a long way to go. Only 15% of undergraduate programs earned an ‘A’ for “adequately covering all of the math topics and pedagogy that elementary teachers need,” according to the policy group.

Teachers’ own math understanding may be a major contributor to their low confidence in teaching it. “Many elementary teachers do not themselves feel adequately confident of their own basic math skills,” report researchers wrote. “They may dedicate less time to teaching math than students need, unsure of how to help their students avoid common misconceptions and errors.”

Time during the school day also plays a significant role. Fuchs, from Vanderbilt, said students who struggle with reading are more likely to also need help in math, but figuring out which skills students are missing, and getting them the proper interventions, takes time and resources, and often means pulling kids out of other core instruction.

“If you are having difficulty in one area, reading or math, your chances that you will have difficulty in the other area is two to three times more,” Fuchs said. “It’s often a logistical nightmare to remediate kids in both areas.”

Data, evidence and organized tracking pays off

But perhaps most importantly, even when students have been properly identified as needing help in math, schools often lack an organized structure and trained point people to guide remediation and monitor student progress. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 48% of schools employ trained reading specialists for this work, while only 23% have math specialists.

“Most every district I’ve worked with, teachers can tell you which kids need help,” said Brian Poncy, associate professor in the College of Education and Human Sciences at Oklahoma State University. “It’s all about the infrastructure in place. Schools need to be able to meet the needs of a diverse set of learners. What’s imperative is that they have the infrastructure in place to meet those needs.”

But at schools like Broadmoor, when organized structures are put in place, and there are trained educators to lead evidence-based interventions, students’ math skills can improve.

After Broadmoor adopted a tiered framework for helping struggling math students, Cindy Apple pointed to a few key changes that made a difference.

They trained teachers on how to interpret data from screeners and benchmark testing, how to use that data to decide what kind and how much help students need, and made time in the daily schedule for 30-minute targeted interventions with teachers, not aides.

Apple also instituted a teacher “common hour” every afternoon—extra planning time. Fourth-grade math teacher Rebecca Finley said the collaboration time has been instrumental in making sure no student falls through the cracks. “I can go talk to a teacher [during common hour], we have that time to put our heads together and problem solve,” she said.

Finally, Broadmoor overhauled the core math instruction that every student gets every day — something experts say keeps more students out of intervention in the first place. They trained teachers in the science of learning, too, so they were better equipped to provide instruction that aligns with evidence on how the brain learns—lack of evidence-based instruction is one of the biggest reasons reading interventions often produce mixed results or fail altogether.

Research-based practices meant to help struggling math students like explicit, systematic instruction, using mathematical language and number lines, and timed activities to increase fluency, also have strong evidence in making general math instruction more effective for everybody, said Elizabeth Albro, commissioner of education research at the Institute of Education Sciences.

Implementing an organized way to assess and track student progress has not only improved test scores, but has kept more students out of serious math intervention. By fifth grade, only 4% of Broadmoor’s students are receiving intensive math help.

Educators like fourth-grade teacher Kristin Brown find the new organization system — the highly detailed, technical work of figuring out what each student needs in math and how to get there — enjoyable, like putting together the pieces of a puzzle.

“To dive into the data is a kind of creativity,” she said. “What is causing those scores to be what they are, and what can we do about it?”

Correction: Kansas launched its statewide infrastructure for supporting students in reading and math in 2008. An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the year the program began.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)