Outgoing Gov. Gina Raimondo’s Education Legacy: An ‘Atmosphere of Innovation’ in Rhode Island Schools

Update: Gina Raimondo was confirmed as U.S. commerce secretary March 2 by a 84-15 Senate vote.

When those who worked alongside Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo reflect on the chief executive’s education legacy, they are unsparing in their praise.

“Hero” and “champion” are the first words that come to mind for Vic Fay-Wolfe, a University of Rhode Island professor who spearheaded the governor’s statewide computer science education initiative.

Meghan Hughes, president of the Community College of Rhode Island, where Raimondo’s tuition-free higher education program spurred dramatic boosts in student enrollment and outcomes, feels similarly.

“She’s helped us prove what’s possible,” Hughes said.

The governor’s leadership, Rhode Island Commissioner of Education Angélica Infante-Green told The 74, has had a clear focus: “How are we going to do what’s right for kids? That has always been the mantra.”

The examples go on and on: Those who worked with Raimondo on school reopenings, on reforming the state’s school funding formula, on early childhood education, on personalized learning all describe the 49-year-old governor, the first woman ever to hold Rhode Island’s highest office, as a relentless innovator pursuing high-quality, equitable education.

But as Raimondo packs her bags in preparation to join President Biden’s cabinet as secretary of commerce after a Jan. 26 Senate hearing that seemed to all but clinch her the job, some observers outside the governor’s sphere take a different stance on her legacy.

“She was pretty much status quo,” said Scott Mackay, a longtime political commentator who recently retired from Rhode Island Public Radio. “I give her like a B, maybe a B-.”

Jonathon Acosta, a freshman state senator and former Rhode Island educator, offered a similarly lukewarm review. “Our schools as a whole in the state aren’t very different today than they were in 2010 — or the year 2000, even,” he said, pointing to student performance data showing stagnation across grade levels.

Rhode Island test scores continue to lag behind those in neighboring Massachusetts, a national leader, and the governor’s efforts to turn around results have been met with mixed responses. Her decisions to greenlight both a state takeover of the Providence school district, which has underperformed for decades, and charter school expansions have each sparked controversy.

But perhaps those very debates speak to something even more essential to Raimondo’s decision-making DNA, a characteristic that will not fade in her role as commerce secretary: She’s hard to pigeonhole, and according to those who worked with her, she leads not by ideology, but by remaining faithful to the evidence.

Data-driven virus response

That trait was never more clearly on display than in the strong stance Raimondo took on school reopenings during COVID-19. Though Rhode Island schools, like the rest of the nation’s, went remote in spring 2020 when the pandemic first hit, by September, while many Democrats remained hesitant to see schools reopen, the governor made national headlines for investing in virus mitigation strategies and demanding that students receive in-person learning options.

The whole strategy, said Dr. Phil Chan, who works with the governor as medical director at the Rhode Island Department of Health, came from a careful look at the epidemiological literature.

“She and her team have been very evidence based and data driven,” he said.

Now, 10 months in, with about a third of the nation’s students still not having attended a single day of in-person school since the start of the pandemic, according to estimates from Burbio, an organization that tracks reopenings, Raimondo’s call to emphasize classroom learning appears prescient. Research indicates that remote learning has caused dangers such as suicide, malnutrition, and severe learning loss to spike among young people, particularly for low-income students and youth of color who were already at risk.

Dr. Chan watched nervously when the state made its initial push for in-person learning in the fall. But now, he said, the data show that Rhode Island schools have seen low rates of virus transmission, thanks to universal masking policies, ventilation upgrades, and testing programs. He believes the governor’s vision was spot-on.

“Virtual learning is not optimal,” he said. “In retrospect, she definitely made the right decision.”

Rhode Island’s Promise

If Raimondo’s push to open classrooms ruffled some feathers, it wasn’t the first time the governor has taken heat. She has long received criticism from the left for her background in finance, which has only intensified since her pick for the Biden cabinet. Before her tenure as treasurer of Rhode Island, the Ocean State native co-founded Point Judith Capital, a venture capital firm that invested in communications, internet, health care and technology companies.

But while many assume that markets and major social welfare investments mix about as well as oil and water, those who worked with Raimondo say that, to the governor, the issues are flip sides of the same coin.

“She understood the financial implications of not having a good education system for our state,” said Commissioner Infante-Green. “We can’t attract businesses to Rhode Island if we didn’t have a great education system.”

The issue is personal for Raimondo. The granddaughter of Italian immigrants, Raimondo comes from a working-class background. Through the GI Bill, her father became the first in his family to attend college. After working for 26 years at the Bulova watch factory in Providence, her dad “started all over again” when the company’s manufacturing moved overseas, according to a 2014 gubernatorial campaign ad. The experience imprinted Raimondo with the memory of financial insecurity — and an understanding of the importance of higher education in the job market.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Eb0N9o8WAKw

In her first term as governor, Raimondo succeeded in creating the RI Promise Scholarship, one of the first of its kind, which guaranteed high school graduates two tuition-free years at the Community College of Rhode Island.

“The governor really put herself behind this program,” said Sara Enright, vice president of CCRI. “She took time, on multiple occasions, to come and sit with groups of Rhode Island Promise students and hear about their experiences.”

To Community College of Rhode Island President Meghan Hughes, the effort showcased Raimondo’s commitment to equity.

“What Promise has allowed us to do is enroll many more low-income students and Black and students of color than we had historically,” she said.

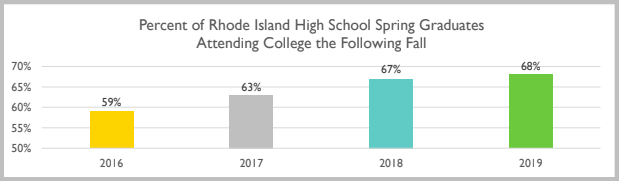

The scholarship program has driven gains in enrollment and degree completion at CCRI, according to a report the program submitted to state officials in 2020. And while critics argue that it has funneled students away from Rhode Island College, a four-year institution that is not included in the scholarship, the overall college-going rate for high school grads in Rhode Island has actually jumped 9 percentage points since the passage of the Promise program.

Though Raimondo declined to be interviewed for this story, the outgoing governor boasted about the program’s success Feb. 3 in her final State of the State address.

“At the time we [approved the Rhode Island Promise program], few states had taken this path,” she told her audience. “Now our country looks to us as a model.”

The state legislature, which allocates approximately $7 million to the program annually, has funded the scholarship through the incoming Fall 2021 class. CCRI leadership hopes, however, that this year lawmakers will pass legislation to lift the sunset provision. On Jan. 29, in a key win for Raimondo’s legacy, state Senate and House leaders introduced a bill to make the program permanent.

Earlier in January, Lt. Gov. Dan McKee, who will step into the state’s top job when Raimondo officially transitions to Washington, told The 74 that he will support such legislation if it lands on his desk.

An ‘atmosphere of innovation’

While Raimondo’s push for free college, if ahead of the curve, played along Democratic party lines, her investments in computer science education and personalized learning are harder to link to partisan affiliation.

In 2016, the governor set an ambitious goal: She called for computer science to be taught in every Rhode Island public school by the end of 2017.

Sure enough, the state hit its target, making Rhode Island, according to Fay-Wolfe, a “national leader” in computer science education. The University of Rhode Island computer science professor attributes that accomplishment to Raimondo’s leadership.

“This would not have happened without her,” he said, citing the governor’s advocacy as a primary reason that the state’s budget now carves out $210,000 annually in direct funds for computer science education. The initiative also receives funds from grants and corporate donors such as Microsoft.

Malika Ali, who works at the Highlander Institute, which partners with communities in Rhode Island to push for more equitable and responsive schooling, agrees that Raimondo created an “atmosphere of innovation” in the state’s education system. The Department of Education, for example, launched a challenge known as the Lighthouse Award to recognize and reward schools using cutting-edge personalized learning strategies.

But the personalized learning push has had hiccups.

Some Rhode Island educators have critiqued the new strategies for relying too heavily on computer programs, particularly in underperforming schools populated mostly by low-income students. These problems have been pervasive in some classrooms, Ali recognizes.

“There were problems in translation,” she told The 74. “I think for some people, they reduced personalized learning to technology.”

The universal computer science push, known as CS4RI, also has had its growing pains. Equity in access has been a problem for the initiative, said Fay-Wolfe. Women and students of color have been underrepresented in computer science programs across the state, as they are nationally.

Taking those disparities to heart, Gov. Raimondo did her best to set a counter-example, he said.

Fay-Wolfe remembers that at a summit coordinated to promote the program, the governor, who had no background in coding herself, took student volunteers on stage and walked them through a computer science exercise together on sorting algorithms.

“She wanted to show that computer science is for everyone,” said Fay-Wolfe.

An unfolding legacy

For all the attention that the Rhode Island Promise scholarship and the CS4RI initiative have received, perhaps no education moves during Raimondo’s tenure as governor have been more high profile than the decision for the state to take over the Providence school system.

Facing persistently low levels of student achievement and intractable leadership struggles, the Rhode Island Department of Education took the reins of the 24,000-student district after a team of Johns Hopkins University researchers released a scathing report evaluating Providence schools in 2019.

Reactions to the takeover were mixed, and now nearly two years later, many question whether it was the right move.

“The Providence takeover by the state has been basically a bunch of halts and stuttering stops,” said Mackay, who watched the district’s progress closely as a political commentator for Rhode Island Public Radio. “That’s something that’s still in limbo.”

But Commissioner Infante-Green cautions against judging changes to Providence schools too soon.

“Education is like a big ship with a little rudder,” she said, pointing to a number of important benchmarks that the district has hit since the takeover, such as upgrades to curricula and new requirements for educators to attend parent-teacher conferences.

Rutgers education professor Domingo Morel agrees that true change will take time. But on key issues like funding, resources for multilingual learners, and increasing the share of teachers of color, Morel, who grew up in Providence and authored Takeover: Race, Education, and American Democracy, thinks Raimondo fell short.

“Were there any mechanisms in place to deal with the issues of resources?” he said, reflecting. “Did we see anything from the governor’s office about … creating opportunities for teachers of color to develop and enter the workforce? The answer there is no.”

Others, however, contend that Raimondo did do her fair share to allocate additional resources to struggling districts. In 2010, the state overhauled its school funding system to channel more money to schools serving disadvantaged populations.

“[The governor] continued to be a strong supporter of the funding formula,” said Kenneth Wong, who was on the team that revamped the equation and works as an education professor at Brown University.

In addition, Elizabeth Burke Bryant, executive director of Rhode Island Kids Count, appreciates Raimondo’s investments in early education.

“She has had a strong vision for universal [pre-K] so that all children would be served,” she said, noting that preschool seats tripled to over 1,800 under Raimondo’s governorship and program quality ranks among the highest in the nation. The state’s overall percentage of 4-year-olds served, however, ranks 35th in the nation.

But though seats may remain limited, they have gone, Burke Bryant points out, to the kids who need them most. “Programs with the highest percentage of lower-income children have had the first opportunity to offer the Rhode Island state pre-K program.”

Given the nature of investments in early education, which studies link to numerous gains down the line for children, like the results of the Providence takeover, it may yet be too early to judge the full extent of Raimondo’s strategy.

As far as Burke Bryant is concerned, however, the governor has done much to move the ball forward toward high-quality, equitable education in Rhode Island.

“We have momentum,” she said. “I am feeling very positively that we will be able to continue to make great progress under the new governor.”

Disclosure: The Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provide financial support to both The Highlander Institute and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)