Will ‘Free College’ Survive COVID-19? How the Pandemic Could Devastate College Promise Programs — and Why the November Election Might Be Their Only Hope

Timari Ray, who recently finished her first year at Pellissippi State Community College in Knoxville, Tennessee, says she probably wouldn’t be able to afford higher education without the Tennessee Promise, which in 2014 made community college free for most students in the state.

Thanks to the Promise, she’s planning to transfer to the University of Tennessee after her second year and eventually open her own public relations firm.

“I at least would have tried [to go to college without the Promise], but I just know that my chances would have been kind of slim because you can only get so many scholarships for tuition, especially at [the University of Tennessee] — it’s a pretty expensive school and it’s kind of difficult to get into,” she said. “So I probably would just be working or maybe going into a trade … I honestly don’t know.”

Ray is currently enrolled in two online summer classes because TNAchieves, the nonprofit organization that administers the Tennessee Promise, is allowing students to use their scholarship money for summer courses this year because of the coronavirus.

The Tennessee Promise is one of a patchwork of more than 400 programs across the country that make college free or more affordable, each designed to serve different students and meet local goals. It’s funded by state and federal grants and an endowment, but the initiatives have different funding strategies, with some relying on philanthropy and others completely dependent on state and local budgets.

Many of these programs could be at risk in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, as mounting unemployment and business closures starve state and local budgets of tax revenue. Without help from the federal government, the programs are “going to be shells of their former selves,” said Douglas Harris, a professor of economics at Tulane University and fellow at the Brookings Institution. Whether that help comes “depends on the outcome of the election” in November, he said.

“Free college” is a popular idea among Democrats, though, and if they win big this year, it could get a major boost.

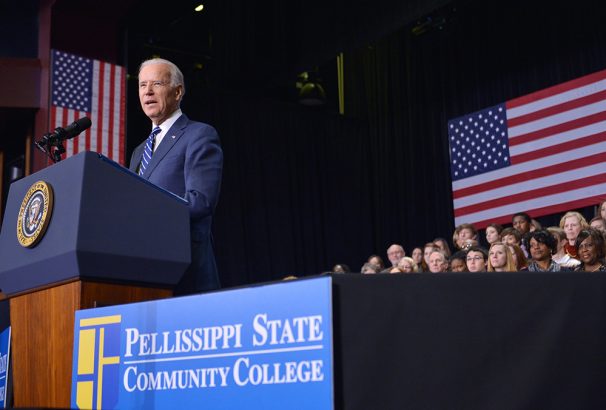

Presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden recently expanded his college affordability proposal in an effort to court progressive voters. He now promises to make community college free and waive tuition at four-year public colleges and universities for those from families making up to $125,000 per year. The Biden campaign also says he will expand access to Pell Grants, the federal aid given to low-income students, and double their value.

“If it becomes a unified Democratic government [at the federal level], then I think that the prospect of free college with federal funding increases a lot. It’s clearly a priority: Biden just upped his commitment, in part to unify the party going into the convention, so he’s now fully committed to that,” Harris told The 74 in an interview.

If Biden wins but Congress is split, with Republicans keeping the Senate, a “watered-down” version might still be feasible, he added, because there is bipartisan support for making some higher education more accessible.

Without federal help, it’s unclear how college promise programs will fare.

The initiatives could continue to operate with less or different funding, Harris pointed out. The programs might force colleges to “accept a smaller amount of money for eligible students” and make up the additional costs themselves. If they receive money from the CARES Act, the $2 trillion relief package passed in March, colleges could use it to meet that need, but if they have to continue the programs without the extra cash, “college quality will suffer,” he said in an email after the interview. The CARES Act sets aside nearly $14 billion for higher education.

At the same time, many colleges are worried about declining enrollment as students consider a gap year or are reluctant to pay steep tuition costs only to take courses online at home. The California State University system, the country’s largest four-year college system, announced in mid-May that most of its fall classes will be online this year. As of early June, ABC News reported that reopening college remained “a big experiment.” Of the more than 870 colleges tracked by The Chronicle of Higher Education, 67 percent said they were planning for in-person classes, 7 percent were preparing for online classes, 8 percent were proposing a hybrid model, 8 percent were waiting to decide and the other 9 percent were considering a range of scenarios.

The average cost of one year at a four-year public college or university was $9,037 for in-state students in 2017-18, the latest year available from the National Center for Education Statistics, though the price varies widely from state to state. Average in-state community college tuition was $3,243 that year.

Free college was one of the issues in the Democratic presidential primary that divided the more progressive candidates from the moderates, including Biden, but the former vice president veered left as the race winnowed. The move was an appeal to Biden’s former rivals in the race, including Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, who said they would make tuition free for all students, regardless of income, at all two- and four-year public institutions.

Biden’s current plan echoes that of former candidate Pete Buttigieg, who wanted to make tuition free for 80 percent of students — those from households making less than $100,000 a year — and subsidize tuition for the next 10 percent by income, or those making $100,000 to $150,000. Mike Bloomberg and Amy Klobuchar vowed to make tuition free at public two-year colleges only.

Most of these plans borrowed from existing promise programs that states and communities have already created for local students.

Four years free for all

The most generous programs cover tuition for four-year colleges and universities.

One of the most comprehensive and best known is the Kalamazoo Promise, started in 2005 when anonymous donors created an endowment to pay for local students to attend college. The Promise pays the full cost of tuition for students who attend Kalamazoo Public Schools for kindergarten through high school graduation. With the scholarship, students can attend any of 56 two- and four-year public and private colleges and universities in Michigan. Students who graduate from a Kalamazoo high school but only attended for a fraction of their school years can benefit from partial scholarships, proportionate to how long they were in the district.

Its reliance on philanthropy also means the Kalamazoo Promise isn’t subject to the whims or budget cuts of legislators. Von Washington, one of the program’s executive directors, said he has been given “reasonable assurance” from the donors that the scholarships are not at risk at this time. A bigger concern, Washington said, is that students might be reconsidering their higher education plans because of the pandemic, though it’s too soon to say what the effect will be.

“We know that we’re in an extremely unique position, never taking it for granted, but it does allow us to continue to focus on what we can do to try to help students feel comfortable about pursuing their postsecondary education no matter what the situation,” Washington said.

Part of what makes Kalamazoo’s initiative so generous is that it’s a “first-dollar scholarship,” which means it pays for students’ tuition outright, regardless of whether students are eligible for financial assistance such as Pell Grants. That means students can use that other financial aid for expenses like books and housing.

Many other promise programs are “last-dollar” scholarships, meaning they cover remaining tuition costs after other financial aid is used. Experts point out that last-dollar scholarships can disproportionately benefit better-off students, who aren’t eligible for need-based aid, because those students receive more money from the program.

Considered an exemplar for free college, the Kalamazoo Promise has now been in place long enough for some data to exist about student outcomes. The Promise, which students have 10 years to use, has meaningfully increased the number of students entering college and graduating, but fewer than half have earned bachelor’s degrees, according to research released in 2017. There’s also a racial gap in degree completion, with about 50 percent of white students graduating, compared with about 15 percent for African-American and Latino students, Michigan Public Radio has reported. About 7,000 have taken advantage of the scholarship so far, program administrators told Michigan Public Radio last year.

Free college for most

Some college affordability programs restrict eligibility by income, as the Biden plan would.

New York state’s Excelsior scholarship, for example, also offers free tuition to two- and four-year public schools to residents from households making up to $125,000 per year.

Going even farther than free tuition, Sen. Brian Schatz, a Democrat representing Hawaii, last year introduced a proposal in Congress that would make all college costs debt free, requiring that federal and state dollars be provided to students to cover tuition as well as living expenses.

Rep. Mark Pocan, a Democrat from Wisconsin, introduced the bill in the House as well.

Warren is a co-sponsor of the Schatz bill, as are Sens. Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Kirsten Gillibrand, who all dropped out of the race for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination.

“Covering tuition for everybody is not a bad idea — it’s just that tuition is only 45 percent of the cost of college,” Schatz told Vox last year. “And I also believe that we ought to cover the full cost of college for people who can’t afford it before we cover tuition for people who can.”

Free community college

Some promise programs offer “free community college” — waived tuition at two-year colleges — so students can earn an associate’s degree and then either transfer to a four-year institution or enter the workforce. As president, Barack Obama pushed for free community college, a program that back then was expected to come in at around $13 billion a year in the long run. In 2015, Obama created an advisory board led by Biden’s wife, Jill Biden, a community college professor, to work on the issue.

The Tennessee Promise, a last-dollar program, provides two years of tuition-free community college or technical school for adults in the state. In addition to financial assistance, it includes a mentoring component that matches students with volunteers who provide encouragement and advice about navigating the transition to college. The program also employs full-time coaches who support Promise recipients throughout college.

Ray, the student from Pellissippi State Community College and a Tennessee Promise recipient, said the coaching component has been critical to her success so far. Her coach, Sumner Deason, meets with her monthly and often sends emails reminding her of things like financial aid deadlines. Ray said Deason, who was a first-generation college student herself, is a valuable mentor who cares about her as a person and encourages her when managing school — and life — gets tough.

“Especially if you’re a first-generation college student, you don’t know what you’re going into, you don’t have your family there who’s been through it to tell you, ‘This is exactly what I did and this is how I got through that,’” Ray said. A mentor or coach can be “someone there to tell you, ‘Oh, I’m proud of you,’ and someone to motivate you to keep going — that’s really big.”

The Tennessee Promise is open to all students who graduate from high school or earn a GED in the state before age 19, though some programs have more restrictive academic criteria.

Hybrid: Free tuition or work experience

In a Democratic debate in January, Klobuchar said leaders should not narrow their focus to college degrees alone.

“I actually think that some of our colleagues who want free college for all aren’t actually thinking big enough,” she said, adding that they should be considering where job openings will be in the future. Research indicates that many of America’s unfilled jobs require more than a high school diploma but less than a bachelor’s degree.

“We’re not going to have a shortage of MBAs. We’re going to have a shortage of plumbers. So when we look at that … Where should our money go? It should go into K through 12. It should go into free one- and two-year degrees, like my dad got, like my sister got,” she said. She added that she would expand Pell Grants “so the money goes where it should go, instead of to rich kids going to college.”

Klobuchar and most of the other former Democratic candidates also expressed support for expanding investment in apprenticeship programs that allow people to earn money while they learn a trade or job.

Under the leadership of Mayor Randall Woodfin, Birmingham, Alabama, is rolling out a promise program this year that includes both higher education and an apprenticeship option. Under the Promise, which is funded by a public-private partnership, students who attend Birmingham City Schools from first to 12th grade can attend a public two- or four-year college for free; students who transfer into the district midway through their education and then graduate can receive a partial scholarship.

Another restriction is that students who choose to attend community college cannot then receive free tuition if they move on to four-year institutions. The University of Alabama at Birmingham announced in mid-January that it will partner with the Promise to help pay tuition for all Birmingham City Schools graduates who are eligible to attend.

In an unusual move, Birmingham has included an apprenticeship component for students who want to earn money while getting work experience. Typically about 50 percent of Birmingham high school grads move on to higher education.

Through the apprenticeship component, high school seniors can work at a local company while earning academic credit and $15 per hour, half paid by Birmingham Promise and half by the employer. Birmingham Promise, Inc., the organization managing the program, has moved some of its student support online to accommodate the pandemic shutdown, and the apprenticeships are currently suspended because schools are closed, a spokesperson said.

In recent weeks, new sponsors have signed on to the program, and Birmingham Promise is planning to begin an official fundraising campaign in late summer or early fall, officials said. They recognize that they “will be contending with the economic consequences of the current health crisis, but are confident the most severe and immediate financial consequences will have passed by that time,” a Birmingham Promise Inc. representative said.

“I wanted to include [the apprenticeship component] because I think about the young people I meet all the time. I know they have career interests. I know they have passions. I know they have these things they want to do,” Woodfin said. “And then I realized they have no exposure, I realized they have no opportunity, and I realized they have no experience to connect that dream they have with a tangible opportunity.”

Fulfilling local needs

An advantage of local promise programs — for the communities themselves, at least — is that they can take local needs into account.

“One of the reasons that I am interested in these programs is that they have the potential to recognize the characteristics of the local context that matter to educational attainment,” such as the “college-going norms” there, the academic readiness of the students and the colleges and universities in the region, said Laura Perna, a University of Pennsylvania researcher who has spearheaded the effort to create a database of promise programs.

But local communities vary widely in the resources they have, Perna said. That raises concerns about college affordability generally and the sustainability of those programs that rely on state and local appropriations, which can be more “volatile” than philanthropy or other funding streams, she said. For example, the Oregon Promise, started in 2016, had to temporarily scale back who is eligible for community college scholarships because of “high turnout and limited funding,” CNN reported.

“It seems like it would be a more effective use of resources if we could figure out how to have federal, state, local, institutions [and] students’ funds all coming together, oriented toward this goal of ensuring that all academically qualified people can go to college regardless of their own resources,” she told The 74. “But I don’t know whether this will happen.”

Birmingham’s Woodfin told The 74 one of the reasons he decided to include apprenticeships in his initiative was because the local business community told him they were having trouble finding workers in industries including health care, manufacturing, technology and energy.

In an attempt to maximize the benefit to the state, New York requires students who use the Excelsior scholarship to reside and work in the state after graduation for the same amount of time that they received the money. Those who do not stay in the state have the award converted to a zero-interest loan.

The small city of Neodesha, Kansas — population 2,400 — has lost more than 1,000 residents over the past 40 years. Ben Cutler, a retired health care company CEO who grew up in Neodesha, last year donated enough money to create a college promise program to last for at least 25 years, The Kansas City Star reports.

He said he wanted to give back to the community that raised him and help it thrive again by attracting young families.

“I probably explored half a dozen different ways that I might use some of my capital resources to improve that community,” Cutler told the Star. “The more I studied it, the more I was convinced that the best bang for the buck I could create was through the Promise program.”

Residents of the city say the announcement has already sparked interest among potential home buyers.

“If there was ever a possibility for something to build Neodesha back up, there’s no doubt that this is the opportunity,” city native Jennifer Marler told the Star. “This is absolutely it.”

What the research says

One drawback to the free-community-college model is that community colleges tend to have lower graduation rates than four-year institutions, as well as smaller budgets.

An economic analysis released by the Brookings Institution in 2019 examined multiple interventions for promoting higher education and found that free community college “increases the proportion of high school graduates who complete a postsecondary degree, but does so at the expense of BA degrees.” That’s because, while some students who would not have pursued higher education do go to community college, some who would have gone to four-year schools switch to community college instead.

On the other hand, community colleges provide the middle skills training required for the open jobs in many communities. Harris, the Tulane economist, noted that this aspect makes community college programs attractive to Republicans.

Before Democrats made higher education affordability a campaign issue, versions of free college had bipartisan support. The Tennessee Promise was largely driven by former governor Bill Haslam, a Republican. The statewide program grew out of Knox Achieves, a privately funded initiative that paid for Knox County students to attend Pellissippi State Community College that started while Haslam was mayor of Knoxville, the county seat.

Another challenge is the tradition of state control in higher education. Researcher Matthew Chingos has argued in The New York Times that the sheer variation among the 50 state college systems, including who is eligible and how much tuition schools collect, would be a major barrier to a federal free college program.

When it comes to public opinion, how a program is structured matters. A study published in January found that people were more likely to perceive as “fair” free college programs that have a merit component, such as a minimum high school GPA, for eligibility. Conducted in 2017, the survey also found that respondents had a more positive view of programs that were available to all students regardless of need compared with those that used an income cap to target families making less than $50,000 per year.

In early February, a Progressive Policy Institute poll of swing voters in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania found that 69 percent preferred to “spend more to help Americans who don’t go to college get higher skills and better jobs” rather than spending more to make college free for everyone.

‘It’s pretty big’

Meanwhile, in communities around the country, college promise programs are opening doors for students.

For Ray, the Pellissippi State student, the opportunity to go to community college for free has been a game changer. She hopes not only to earn a bachelor’s degree and start her own PR business but also to encourage her younger siblings to do the same.

“It’s pretty big,” she said. “I go home and see my family [and] they just tell me how proud they are of me and how they want me to just keep going even though sometimes it gets tough … I’m the only one being a role model for my younger siblings so they can go to college.”

She plans to stay in Knoxville for years to come in part because of how the community has invested in her education.

“If I was somewhere else and they didn’t have anything like that, I wouldn’t want to stay there,” she said. “If I wasn’t able to get free education, then that wouldn’t be the best place for me.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)