Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

When the pandemic first struck, many child well-being advocates worried that the massive shift to remote school would spur an uptick in a troubling behavior: online bullying.

According to new research from Boston University, however, virtual learning may have had precisely the opposite effect.

During online school, “there’s no increase in cyberbullying, and in fact, there appears to be a decrease,” co-author Andrew Bacher-Hicks told The 74.

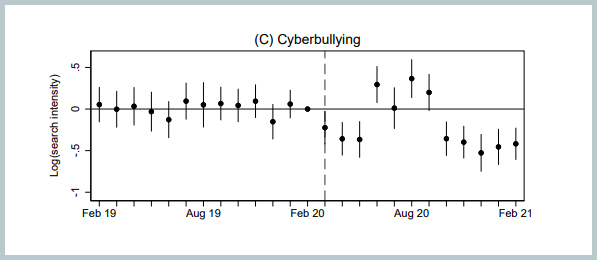

He and his colleagues’ working paper, published through Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, used Google search trends to track rates of bullying and cyberbullying through the pandemic. Google search intensity for those two terms, the authors found, represents a strong proxy for actual rates of bullying in school and online.

Overall between March 2020 and February 2021, when the majority of students in the U.S. were learning remotely, the rate at which internet users searched for “school bullying” dropped 33 percent below pre-pandemic levels and the rate at which they searched for “cyberbullying” dropped 20 percent, according to the paper from Boston University’s Wheelock College of Education & Human Development.

“We were surprised by the drop in cyberbullying,” said Bacher-Hicks. “It stands in contrast to the belief that [the shift to online instruction] would increase cyberbullying.”

Normally, 1 in 5 youth report being bullied in school each year, and 1 in 6 report being bullied online, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. For students involved in bullying — whether as a victim, aggressor or even just a witness — “rates of mental health problems are higher, school attendance is lower, and students are less likely to feel safe,” co-author Jennifer Greif Green told The 74.

Amid reports of young people’s academic struggles and social isolation while learning remotely through the pandemic, the drop in bullying represents an unexpected benefit for students whose departure from the schoolhouse walls also meant a respite from peers’ abuse.

Social isolation is “a matter of life and death for children,” Laura Talmus, executive director of Beyond Differences, told The 74. Her nonprofit promotes social-emotional learning resources with an emphasis on social connectedness, belonging and online kindness.

In the spring of this past school year, when more students returned to classrooms in person, rates of bullying, both in school and online, rose back up — but not all the way to pre-pandemic levels, the BU paper finds. That checks out, says Bacher-Hicks, because even where schools had fully reopened, not all students actually chose to attend in person.

“There could be, you know, 50 percent of students at each school … that aren’t going, so it still could make sense that a drop in bullying could occur,” the Boston University researcher explained.

Separate research, also published in July, clarifies that school bullying can have especially negative effects on youth of color who also hold another identity — such as gender, sexual orientation, income, religion, disability or immigration status — that targets them for ostracization.

The Boston University authors present multiple potential hypotheses for the reduction in online abuse. First off, prior research indicates that in-person bullying may actually drive online bullying, so drops in the former could directly spur drops in the latter, they point out.

“Many of the same students who are involved in cyberbullying are also involved with in-person bullying,” said Green. “We see the same students are engaged in both.”

“If that in-person bullying is no longer happening, maybe that cyberbullying would also decrease,” added Bacher-Hicks.

Another theory? That the additional time young people were spending online over the past year — often on Zoom or Google classroom — was more structured than other forms of screen time. Studies show that when young people spend more time on social media, it’s often tied to increasing rates of cyberbullying, but another body of research clarifies that bullying tends to take place during unstructured time at school such as passing periods or recess.

“Because the online time during remote learning was more structured and had more adult oversight, there may have been less … cyberbullying during that time,” explained Green.

That doesn’t mean schools should indiscriminately clamp down on all unstructured time in the school day, the bullying expert explains. Rather, schools should work to create optional teacher-led activities at lunch and recess for students looking to avoid unsupervised activities with their peers, says Green.

“Different students have different needs in terms of social skills development and the extent to which they benefit from having adult oversight,” she said.

As schools plan to return fully in person this fall, Green is left with one animating question on the heels of her team’s research.

“What can we take from this moving forward that would be most helpful as we’re thinking about what schools can look like in the future?”

If you or someone you know is being bullied, resources and information are available at stopbullying.gov. Beyond Differences offers free resources for parents and educators to combat social isolation.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)