New Research: School-Based Cops Reduce Campus Violence — But at a Steep Cost, Especially for Black Students

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

School-based police effectively combat some forms of campus violence including fights, according to a major new report, but their presence increases the number of students facing suspensions, expulsions and arrests, particularly if they are Black.

In fact, researchers found that the harms of school policing may outweigh its benefits. In addition to making it more likely that students will face exclusionary discipline, such as suspension and expulsion, students are chronically absent more when campuses are staffed by cops, with researchers identifying a marked spike in missed school days among youth with disabilities.

The results, researchers note, suggest that school-based police could hinder students’ academic outcomes, increase their long-term involvement with the criminal justice system and appear to “seriously exacerbate existing opportunity gaps in education.” The effects of school police on discipline and arrests were “consistently over two times larger for Black students” than their white classmates, the study found.

“There might be these benefits in terms of reduced violence, but there are also these really large costs, and costs that unequally affect students,” said report co-author Lucy Sorensen, an assistant public administration and policy professor at the University of Albany, SUNY.

“At the end of the day, I have a hard time, as an education researcher, thinking this is what we should invest money in,” Sorensen added.

The report, a working paper released by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University that has not yet been peer reviewed, is the first school-level examination of campus officers across every public school in the U.S. It is also one of the first pieces of in-depth research on the effects of school police to follow a nationwide movement to remove cops from schools that was prompted by the death of George Floyd and argued their presence was especially harmful to students of color.

School security consultant Kenneth Trump, president of the National School Safety and Security Services in Cleveland, maintained that campus police can be a positive force so long as they’re implemented through industry “best practices,” including a clearly defined selection process for officers who receive specialized training.

“If you have a properly designed and implemented, supervised and evaluated [school resource officer] program, there are many positive things about that,” he said. “That said, if you have an SRO on your campus, chances are you’re going to see some increase in arrests by the mere fact that the officers are going to identify crimes that school administrators may previously have not recognized and reported.”

The number of officers stationed in K-12 schools has grown exponentially in the last several decades, largely in response to school shootings, and the federal government has spent more than $1 billion to facilitate that increase. In the 1970s, just 1 percent of schools had police stationed on campus. Today, that figure has jumped to roughly half.

School shootings remain statistically rare and campuses have grown markedly safer in the last several decades. But the new report throws cold water on a common argument in favor of school policing: Officers failed to prevent school-shootings and other gun-related incidents. In fact, having an officer on campus “marginally increases the likelihood of a school shooting,” according to the report.

Future research should explore the factors that drive that increase, Sorensen said. Though shootings have long motivated police presence in schools, preventing such tragedies is “not what the job entails on a day-to-day basis,” she said, and instead officers “are getting involved in minor disciplinary matters.”

George Floyd’s murder in 2020 at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer ignited a heated national debate over the broader role of police in the U.S., and several districts ended their ties with the police or slashed their policing budgets. In Minneapolis, for example, the district terminated its police contract and replaced officers with non-sworn safety agents who lack arrest authority. Several dozen districts nationally made similar decisions as advocates highlighted racial disparities in school-based arrests that fed the school-to-prison pipeline and called on educators to replace cops with counselors and other student support services.

On Wednesday, the City Council in Alexandria, Virginia, voted to temporarily reinstate its school resource officer program five months after it pulled police from hallways. The reversal followed parent outrage in the wake of multiple campus safety incidents.

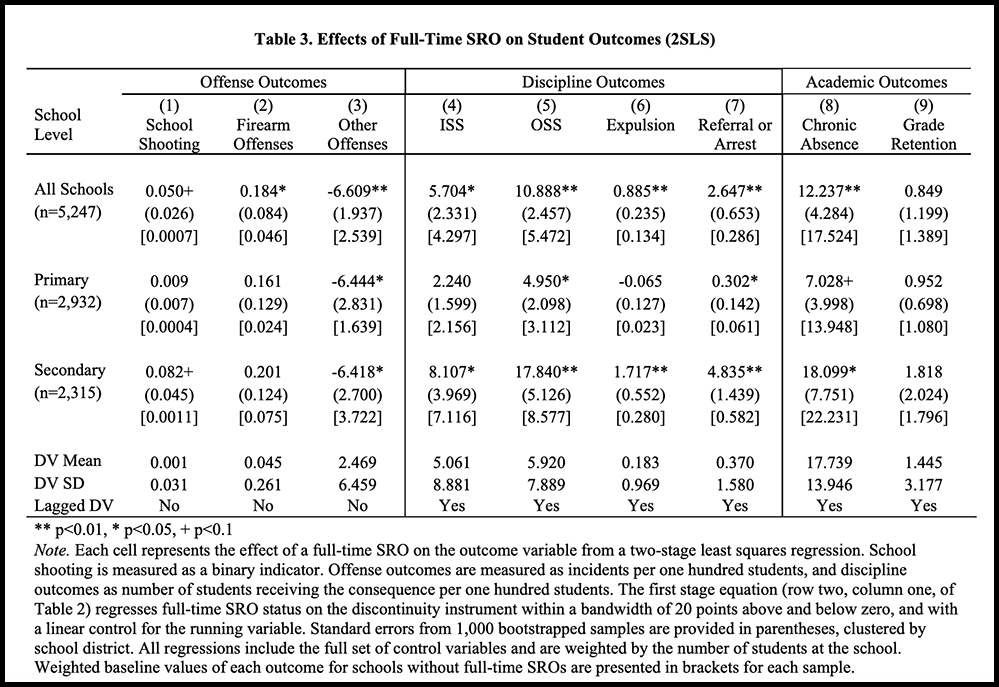

The latest research, however, further bolsters a body of evidence on the negative effects of placing police in schools. To reach their findings, researchers analyzed federal education data between 2014 and 2018 and data on law enforcement agencies that applied for federal grants between 2015 and 2017 for school-based policing. In a given year, officers led to a reduction of six non-firearm violent incidents per 100 students, according to the report. They also increased the out-of-school suspension rate by 10.9 students per 100. The increase in student punishments was starkest in middle and high schools where, per 100 students, 17.8 more received out-of-school suspensions, 1.7 more were expelled and 4.8 more were referred to police or arrested. Additionally, results suggest that school police increase chronic absenteeism by 12.2 students for every 100 kids enrolled, and an increase of 13.4 students per 100 among those with disabilities. Across disciplinary outcomes, the results were starker for Black students than their white classmates.

Overall, the results suggest that stationing police in schools “intensifies the levels of punishment unevenly across different groups of students, and that Black students, male students and students with disabilities generally bear the brunt of this punishment,” according to the report.

The new report follows a recent study on the effects of school resource officers in North Carolina, which reached similar conclusions. In a recent analysis of federal data by the Center for Public Integrity, the nonprofit news outlet found that schools disproportionately referred Black students and those with disabilities to the police at a rate nearly double their share of the overall student population.

“If you’re going to throw out your SRO program, then you should also throw your administrators out with it because they have been partners in those programs all along,” Trump, the security consultant, said. “It’s not just the police who must be screwing up.”

Ben Fisher, an assistant professor at Florida State University’s College of Criminology and Criminal Justice, noted the consistency of the latest research with the North Carolina study, which found a “trade-off between some marginal decreases in school crime and some pretty serious increases in the exclusion of students through suspensions and arrests.” Fisher said it adds to a growing body of research highlighting that school resource officers have a detrimental effect on youth outcomes, while pointing out that other people could view the evidence through a different lens.

“I don’t think it’s good to exclude students from school or arrest them,” said Fisher, who has researched the efficacy of campus police for years but wasn’t involved in the latest report. “Other folks could read that same research and say, ‘There’s more arrests — good. They ought to be removed from schools if they’re doing bad things.’”

When interacting with students, most school-based officers seek to avoid arrests, according to a new survey by the National Association of School Resource Officers, a trade group. About a third of campus arrests are based on observations from officers, according to the survey, and a similar share began with a referral from school staff.

Ultimately, policymakers should weigh the decreases in campus violence against the other effects of school policing and decide whether other interventions could be more effective, the researchers concluded.

“Interventions should not just be judged on a single outcome, but comprehensively on many outcomes,” the report states. “It also suggests that the comprehensive impact of using resources for school police should be compared with the comprehensive impact of using resources in other ways to improve school safety and climate,” including the use of restorative justice in schools, which researchers described as “a single intervention to both reduce suspensions and improve school climate.”

As school-based police continue to generate passionate debate and additional research emerges about their efficacy, Sorensen said she expects education leaders to increasingly explore alternatives like investing additional money in social workers and mental health services for students.

“I think we’ll see a lot of different experimentation in the coming years,” she said, “and I hope we can learn from that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)