Analysis: Maybe the Problem With Police in Schools Isn’t Just the Police — a State-by-State Breakdown of How Often Schools Call the Cops

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Mike Antonucci’s Union Report appears most Wednesdays; see the full archive.

The Center for Public Integrity has produced a lot of work about the issue of police in schools. This latest effort adds a new perspective. While focused on the misdeeds of cops in classroom settings, it also shines a light on those schools, districts and states that call in the police a disproportionate number of times.

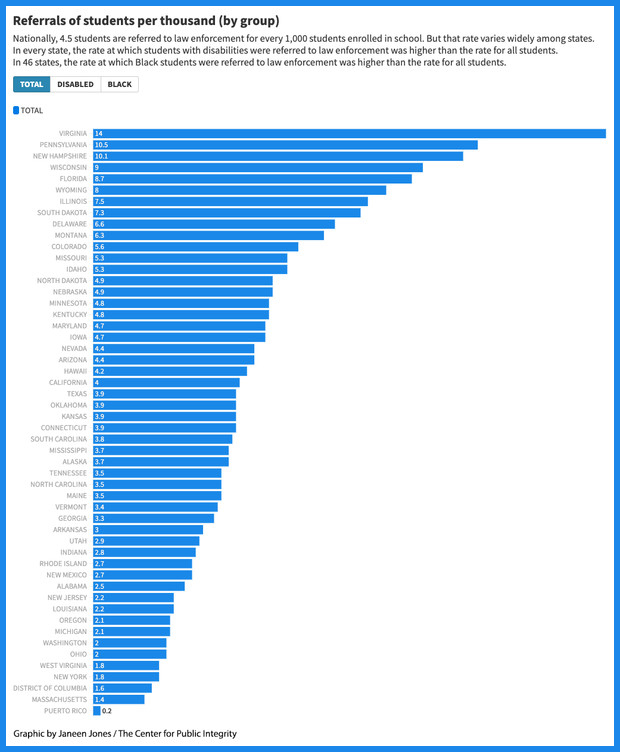

This chart shows state rankings by the number of times students were referred to law enforcement. Nationally, the average is 4.5 students for every 1,000. But some states go way beyond that, and political leanings do not seem to be a factor.

School officials in Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Wisconsin all called the cops on students at a rate at least double the national average. At the other end of the scale, some states with very large school districts, such as Massachusetts; Washington, D.C.; New York; and Ohio, called the police far less often.

In virtually every state, Black students and those with disabilities were referred to law enforcement at rates higher than those for all students.

While incidents of police violence and improper arrests of students made headlines, districts were also making questionable decisions in funding school police. The American Civil Liberties Union got involved in Vermont when it discovered that at least two school systems were using Medicaid reimbursement funds to pay for school cops. The money is supposed to be used to “facilitate early identification of and intervention with children with disabilities.”

The Des Moines, Iowa, school district canceled its contract with the city police but admitted school officials were also responsible for mishandling the use of security personnel.

“In the community, it came off as [the police] are the problem. If it was that easy, we probably would have identified that a long time ago,” said Jake Troja, the district’s director of school climate transformation. “The issue is, systematically, the overuse of law enforcement and underpreparedness of our school system to respond to safety violations and violations of law in an equitable manner.”

Police assigned to schools and called to school incidents need to be held to account for their actions. But that addresses only half the problem. School systems wanted them there in the first place and have been calling the cops for classroom disruptions that don’t involve criminal behavior.

It’s important to have the right personnel for the right situation. “Cops are trained to be cops,” said Marilyn Mahusky, a staff attorney for the Disability Law Project at Vermont Legal Aid. “Consistent with their training, they demand that the behavior stop, and if it doesn’t, you’re charged, you’re arrested.”

Teachers and other school employees might have to make some tough calls when a student outburst appears to be getting out of hand. It’s not always easy to identify whether a situation is juvenile acting-out or an actual danger to other students and staff. A physical and authoritarian response is sometimes the only remedy. But it is a good general rule to try to defuse potentially aggressive behavior at the lowest possible level of outside intervention. Calling in the cops should always be a last resort.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)