New Research: Babies Born During COVID Talk Less with Caregivers, Slower to Develop Critical Language Skills

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

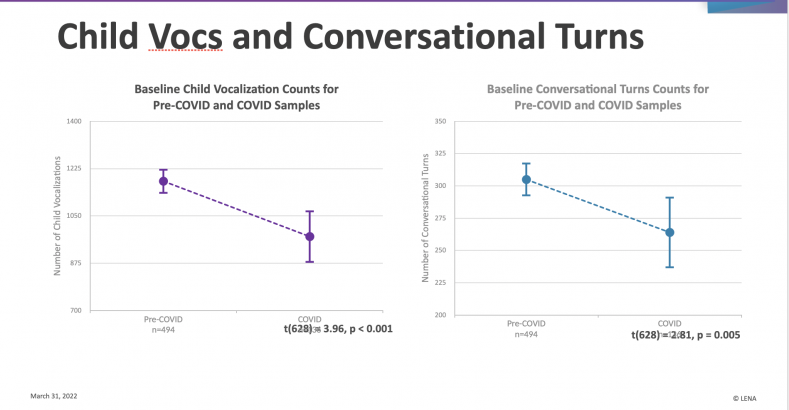

Infants born during the pandemic produced significantly fewer vocalizations and had less verbal back-and-forth with their caretakers compared to those born before COVID, according to independent studies by Brown University and a national nonprofit focused on early language development.

Both research teams used the nonprofit LENA’s “talk pedometer” technology to glean their findings. The wearable device delivers detailed information on what children hear throughout the day. It measures the number of words spoken near the child in addition to the child’s own language-related vocalizations.

It also counts child-adult interactions, called “conversational turns,” which both research groups say are critical to language acquisition.

“It is the conversational turns that drive brain development,” said Brown’s Sean Deoni, adding he’s concerned for the long-term success of children born after the pandemic began.

The joint finding is the latest troubling evidence of developmental delays discovered when researchers compared babies born before and after COVID.

Deoni is principal investigator at Brown’s Advanced Baby Imaging Lab. He and other staffers there first spotted the problem when they noticed that children who visited the lab after March 2020 took longer to complete cognitive tasks.

“They were not as attentive, or at least not performing as well as we normally have seen,” Deoni said. It was this change that prompted him to take a new look at various data points gathered from the nearly 800 children his facility has worked with in recent years. After examining their neuroimaging and neurocognitive results, he and his team found child motor and language scores decreased sharply in 2021 and 2022, prompting them to search for an explanation for the decline.

The inquiry led them to analyze information gathered from children ages 12 and 16 months who were born before 2019 — well before the COVID outbreak — and after July 2020, months into its spread. The results showed a major drop in verbal functioning between the two groups. Those born after COVID demonstrated slower verbal growth over time.

Tests showed, too, these babies experienced a significantly slower rate of white matter development versus the children from studies done before the pandemic.

“White matter is basically the wiring of the brain,” Deoni said. “It’s what carries information throughout the brain and to different cortical regions where it is processed. White matter damage, for example, is a hallmark of multiple sclerosis. Reduced white matter development is associated with reduced cognitive development.”

Deoni and his team also found a significant drop in adult words per hour and conversational turns between the two groups of children. The deficit will have a significant impact on kids he said, citing his own group’s earlier research.

Neither research team focused on the cause of the drop in caregiver interactions with babies, only the outcome, though Deoni cited the heightened stress, depression and burnout associated with the pandemic as possible explanations.

Jill Gilkerson, a linguist specializing in early language acquisition and LENA’s chief research and evaluation officer, said the reasons might differ from one household to the next.

“I don’t think we are going to be able to find a single cause to point to, and I’m not sure that we need to,” she said. “We hope this data validates concerns caregivers may be having, helps them know they are not alone in those feelings and furthers the conversation about the need to invest in support for families at every level.”

LENA’s study showed child vocalizations dropped significantly across all groups of children, but particularly among those from the lowest socioeconomic level. The frequency of caregiver/child conversations also decreased dramatically, particularly among children from the poorest families, it found.

“It’s often the case that when these adverse events happen, it’s those who are already the most vulnerable that are hit the hardest… and I think that we are seeing this here,” Gilkerson said.

The connection between economic security and language acquisition was very much a pre-pandemic concern as well. A landmark 1995 study found that children growing up in low-income households hear 30 million fewer words than their peers from high-income backgrounds. A 2018 study raised questions about the extent of the gap, but the science is clear that children’s first three years are the most critical time for brain development.

LENA, based in Boulder, Colorado and founded in 2004, aims to improve children’s futures through early talk technology and data-driven programs. Its software measures a child’s language environment and provides feedback to parents and professionals vested in preparing them for school.

Its study of 136 COVID-era babies included only those who started gestating on or after the start of the pandemic in mid-March 2020: All were born after December 15 of that year. The findings from this group were compared to a pre-COVID pool, which captured recordings between 2017 and March 2020 and included 494 kids.

These language deficits, once shared with caregivers, are possible to correct. But, Gilkerson said, it’s important for groups like hers to suggest practical, easily applicable solutions.

“We need to … provide parents with strategies for integrating talk — interactive talk, quality talk — with their children during their regular routine,” she said, rather than add a new task to their already stress-filled lives.

LENA’s latest research builds off earlier findings the group published in the journal Pediatrics in October 2018: That study showed early talk and interaction, particularly for children ages 18 to 24 months, can predict school-age language and cognitive outcomes. In that paper, LENA examined day-long audio recordings for 146 infants and toddlers completed monthly for six months.

LENA’s Language Environment Analysis software measured the total number of adult words and adult-child conversations. LENA conducted follow-up evaluations at 9 to 14 years of age. It concluded that adult-child conversations influence a child’s IQ, verbal comprehension and vocabulary scores 10 years later.

And while it’s true, both researchers acknowledged, that children are resilient, recent data does not yet reflect the bounceback from the pandemic.

“We are not seeing them hit a floor and all progressively get better,” Deoni said. “We are seeing them continue this downward trend.”

And it’s not just a language acquisition problem. Reduced verbal development is being driven by poor motor development, Deoni said: This early foundational skill could have a lasting impact on children, one that can be hard to correct for as they age.

“I’m worried about how we set things up going forward such that our early childhood teachers and early childhood interventionalists are prepared for what is potentially a set of children who maybe aren’t performing as we expect them to,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)