Maryland’s Humble Mission: Build the Nation’s Best, Most Equitable School System

The “Blueprint” plan will take a decade to fully implement, eventually adding $3.8 billion per year to the state’s education system

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It was March 2020 and the world was collapsing around Anne Kaiser as the coronavirus pandemic swept across the nation. But with the Maryland legislative session forced into an abrupt close, the state lawmaker knew there was one bill she and her colleagues needed to push over the finish line.

The “Blueprint for Maryland’s Future” had been in the works since 2016, when the legislature set up an expert commission with a humble charge: Develop a plan to remake Maryland’s schools into some of the very best in the world.

In a Sunday emergency legislative meeting just before the COVID shutdown, the landmark policy, all 235 pages of it, passed with bipartisan support.

“We certainly weren’t gonna let that legislation go another year when we were so close … and [knew] how important it was,” Kaiser recalls.

Now, over two years later, Maryland has begun its decades-long, multibillion-dollar mission to transform its schools. One superintendent called the effort a “seismic shift” for education in the state. A researcher described it as a “radical reimagining” of schooling.

But outside the Old Line State, the Blueprint has barely made a splash, garnering little national attention.

“It’s sort of passed under the radar,” said William Kirwan, who chaired the commission that drafted the legislation.

As the policy rolls out, he suspects “the results will begin to get noticed and … we can be a bellwether for the rest of the country.”

The Blueprint’s highlights include:

- Free preschool for all low-income families

- A revamped teacher pipeline to diversify candidates and boost minimum pay to $60,000 per year

- A new model of secondary school that prepares all students for college or careers by 10th grade, leaving the final years of high school for apprenticeships and advanced coursework

“The changes are so significant, we’re basically building a new system of pre-K through 12 education,” said Kirwan, who was the longtime chancellor of the University System of Maryland.

Districts will phase in the plan over a 10-year period and the policy will ultimately inject an additional $3.8 billion annually into the state’s education system. That shakes out to a 22% increase in overall education spending in the state, or about $4,000 more per student per year, noted Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown’s Edunomics Lab.

Funding comes from taxes on casino revenues and internet sales, among other sources. A newly created Accountability and Implementation Board, of which Kirwan is a member, will guide districts through the upcoming changes and approve or deny their improvement plans.

Closing opportunity gaps

Not only does the Blueprint aim to raise the state’s overall academic achievement, which Kirwan calls “mediocre” based on past results from the Nation’s Report Card, it also seeks to correct what many experts describe as a highly unequal school system with a regressive finance structure.

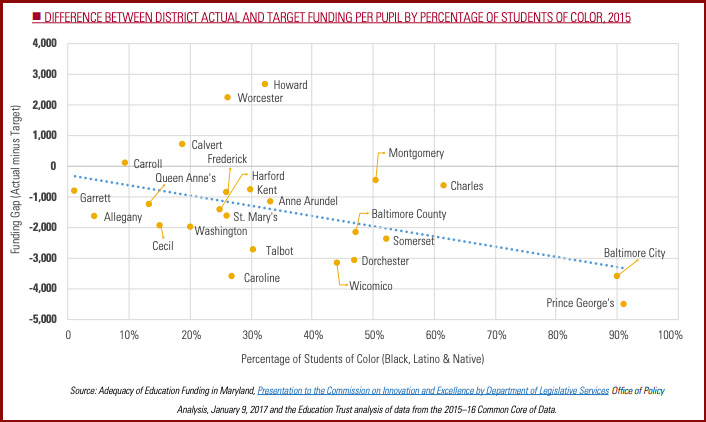

Baltimore City and Prince George’s County schools serve the highest share of Black and Hispanic students in the state and for years have received among the least per pupil funding of any district — $3,600 and $4,500 below the level recommended in the state funding formula, respectively.

“The most persistently underfunded school systems in the state disproportionately educate the most Black and brown kids,” said Shamoyia Gardiner, executive director of Strong Schools Maryland.

The Blueprint will vastly reduce that imbalance by infusing the largest share of funds to the neediest districts. Its formula adjusts funding levels based on a measure for concentration of poverty. The formula does not consider racial makeups after the state attorney general said doing so would be illegal, Gardiner explained.

“The promise of the Blueprint is that in a world-class system, most of our kids are going to succeed and we’re not going to be able to tell these differences along the lines of race or class,” she added.

Now in the wake of COVID, which hit vulnerable students such as those from low-income families the hardest, the stakes for faithfully implementing the Blueprint have only been elevated, said Education Trust researcher Robert Ruffins.

“The gap that already existed … has widened, but we have the opportunity to close it if we get this right,” he said.

Trepidation & promise

Some observers criticize the mammoth policy, arguing that while it heaps funds toward schools, it has no mechanism to guarantee that the proposed changes deliver their intended effects.

“It’s kind of a wish list of all the things we think will make Maryland schools better without a promise that when we spend all the money these things will be fixed,” said Annette Anderson, a Johns Hopkins University education professor whose three children attend Baltimore City Schools. “I don’t feel like we have the accountability. … How do we measure that we’re making progress on this?”

Kirwan counters that the nature of the policy mitigates that concern. Districts are required to submit their plans to an independent body “with real teeth,” the Accountability and Implementation Board, for review and possible amendments to ensure they roll out changes faithfully, he said.

Rachel Hise, executive director of the accountability board, added that a quarter of each district’s annual Blueprint funding will be automatically withheld until the board decides to release it. Starting in 2026, that decision will include whether the school system has made sufficient progress to improve student performance measured, in part, by test scores.

Still, school leaders fret whether some of the changes will be feasible for districts already weakened by educator shortages and seeking to recover lost ground from the pandemic.

John Woolums, director of governmental relations for the Maryland Association of Boards of Education, describes himself as a “cheerleader” for the Blueprint, but acknowledges that some of the school boards in his network have trepidations about implementation. The policy requires schools to gradually reduce teacher caseloads so they can devote time during the school day to small-group tutoring and intervention.

“Just the math of that requires that you have additional staff to meet the needs of other students during that time,” Woolums said.

Another issue that will require “outside-the-box thinking,” said Hise, is physical space for expanded preschool programs. One possible solution she points to is running early child care centers within high schools. With more upperclassmen out of the building during the day for apprenticeships, some classrooms will be unoccupied, she anticipates. At the same time, the programs could give interested high schoolers new real-world learning opportunities.

“You’ve got 11th and 12th graders who are apprenticing within that child care center … learning a new field while they’re still in high school,” she proposed.

Michael Martirano, superintendent of the roughly 57,325-student Howard County Public School System, said he’s actively considering that option. It’s an example of how the different prongs of the Blueprint can reinforce each other and bring about innovative solutions, he said.

“There’s synergy and energy around all of these [components] to think differently about getting better results for kids with this infusion of dollars from the state,” the superintendent said.

Even in the early years of implementation, Martirano has seen how the provisions of the Blueprint have given him leverage to make changes he’s long wished for.

For example, with the Blueprint’s mandate that teacher minimum salaries eventually reach $60,000, the leader proactively brought his district’s floor up to $56,000 last year, which he said largely insulated Howard County from recent teacher shortages affecting nearby districts. The school system hired a record 500 new teachers this year and had less than 1% vacancies for teacher roles, he said.

“Things that I may have wanted to advance before … that may have been difficult to implement in the past are now an expectation,” Martirano said. “These are not negotiables. These are things that now have to be done.”

‘In it for the long haul’

But even with early signs of progress, Hise, who penned most of the bill’s text as a legislative analyst, knows that the road will be long before the policy is implemented in full.

Alongside some of the top-performing international school systems, the 2016 legislative commission studied Massachusetts, which since the 1990s has adhered to a comprehensive school improvement plan and is now touted as one of the best U.S. states for education. It took decades of work to get to that point, Hise observed.

Still, there are shortcomings, she said.

“[Massachusetts schools] still have an achievement gap that they need to close,” said the policy expert. “The [Blueprint’s] goal is to raise all boats and also close the gap.”

Gardiner, of Strong Schools Maryland, hopes her state will stay committed to the policy’s provisions, which, to her concern, have already seen slowdowns. Republican Gov. Larry Hogan vetoed the original bill in 2020, forcing a veto override vote from the legislature in 2021 and setting the implementation process at least a year behind. Democrat Wes Moore will replace the term-limited governor in January, but further out, especially as several economic indicators point toward a possible recession, she fears commitment could wane.

“The fact that we are already so delayed … makes me want to ensure that we don’t slide any further away from our original vision,” Gardiner said.

The policy finds a key ally in State Superintendent Mohammed Choudhury, who has said the Blueprint is one of the “main reasons” he took the top job in Maryland schools in 2021. The state has an opportunity to become a leader in high-quality, equitable education, he says.

The responsiveness to community feedback instills confidence in sharlimar douglass, leader of the Maryland Alliance for Racial Equity in Education. (She does not capitalize her name.) The accountability board has held a series of virtual working sessions that douglass, who has attended each one, estimates typically draw at least 90 people.

“The process by which the board is working to make sure that all stakeholders are heard from has been excellent,” the advocate said. “Everything that’s put in the chat seems to be responded to.”

Hise, for her part, is keeping her focus on the future.

“Systemic change takes time,” she said. “You can’t look at it in two- or four-year terms. You have to be in it for the long haul and you have to be committed to it across election outcomes and changes in leadership. It has to be above all of that. That’s the goal.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)