Labor in the Age of Janus: 6 Things to Keep in Mind About American Unions on the Eve of a Pivotal Supreme Court Ruling

Updated June 13

The Supreme Court will soon hand down a decision in Janus v. AFSCME, the exhaustively discussed challenge to laws requiring government workers who don’t join unions to cover the cost of services they benefit from, such as collective bargaining and arbitration.

The court affirmed the constitutionality of these charges in Abood, a unanimous 1977 ruling that distinguished between union dues, which may contribute to political activity and must be voluntary, and “fair share” fees that help pay for union representation. Conservative and right-to-work groups have repeatedly challenged the decision.

In February, lawyers for an Illinois state employee named Mark Janus argued that because union negotiations involve political issues like budgets and taxes, mandatory fees infringe on workers’ free speech.

Nearly everyone believes that the justices will rule for Janus, largely because they deadlocked 4-4 on a similar case in 2016 and Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch has since come aboard. Unions and their supporters have warned of potentially cataclysmic membership and revenue losses as workers no longer need to pay dues to enjoy benefits.

Many Democrats believe the constitutional argument is a Trojan horse for right-wing funders hoping to weaken organized labor and its formidable political clout. Unions are among the largest donors to Democratic candidates and have strong turn-out-the-vote operations.

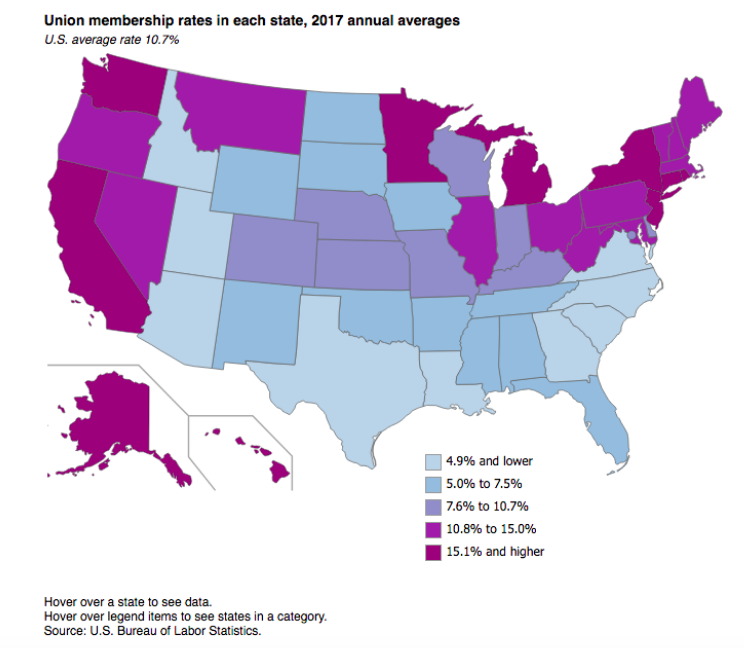

Should the case be decided unfavorably for unions, it will affect only the 22 states that still have agency fee laws, but these include powerful workers groups in states like California and New York.

The court will hand down its decision at a busy and unpredictable time for American unions — and for unionized teachers. Here are six things to keep in mind about what it means for the future of the labor movement:

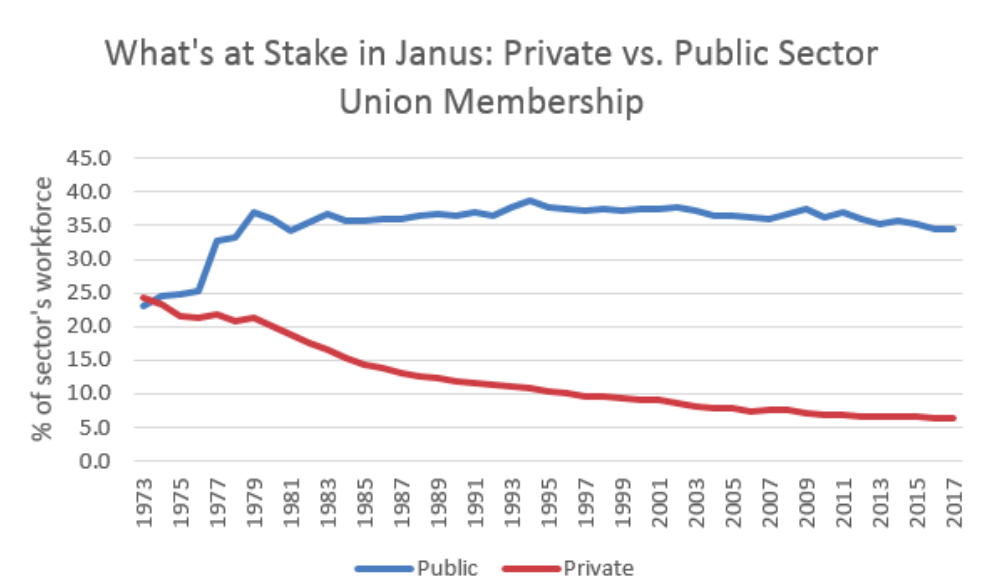

1 Janus is a threat to labor because government employees are most of what’s left in the movement.

In 1970, 29.1 percent of employees in the workforce belonged to unions. In 2017, that figure was 10.7 percent. Government employees are mostly staying in their unions, however — 34.4 percent were unionized last year. But the rate for private employees, which dwarfed the public-sector rate when the country was a manufacturing colossus, is now at an endangered-species level of 6.5 percent, roughly one-quarter of the size it was in the 1970s.

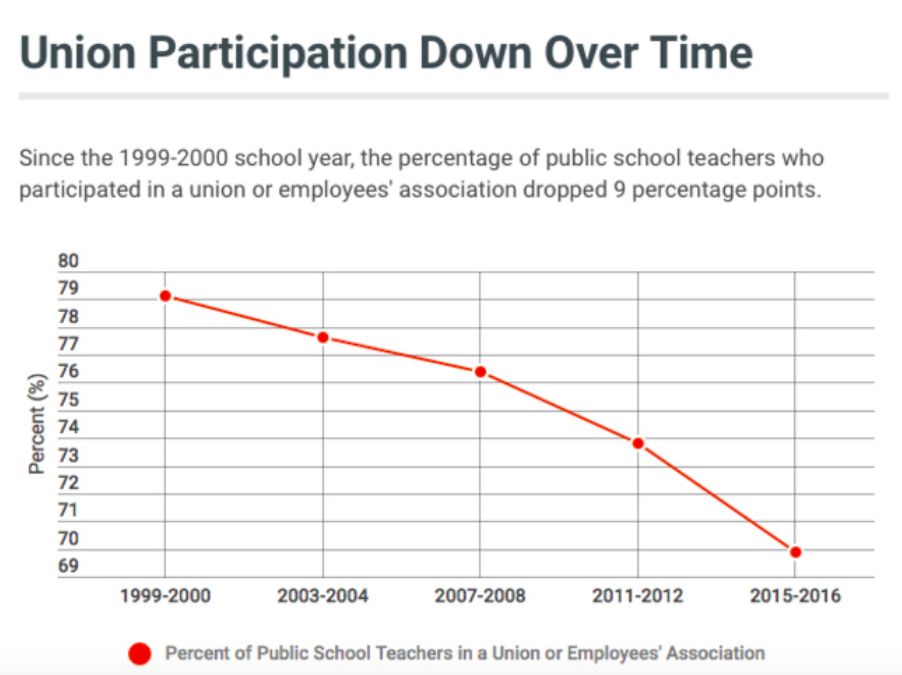

While their membership rates are still high, teachers are also less likely to belong to unions: In the 2015-16 school year, roughly 70 percent were unionized, down 9 points from 1999-2000, according to a U.S. Education Department survey.

2 Janus will affect states where union members are heavily concentrated.

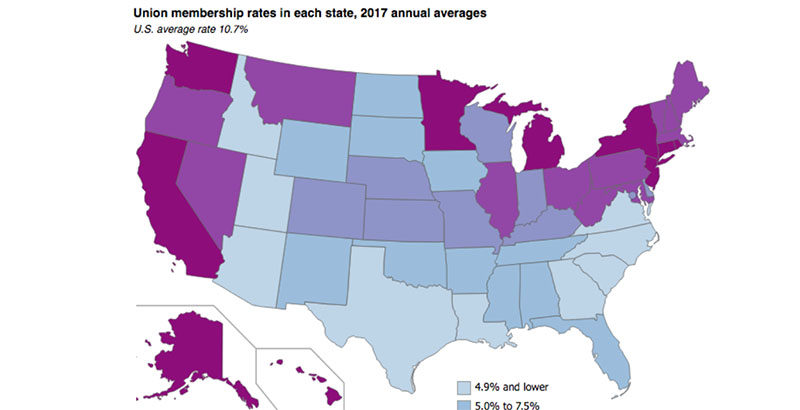

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, more than half of the country’s 14.8 million union members lived in seven states in 2017: California (2.5 million), New York (2 million), Illinois (800,000), Michigan and Pennsylvania (700,000 each), and New Jersey and Ohio (600,000 each). Except for Michigan, all have agency fee laws. This BLS map allows users to hover over individual states for the number and percentage of unionized employees. This nifty NPR map shows how each state’s unionized population has changed since 1964.

3 Research: How Janus may affect a.) the country and b.) public education.

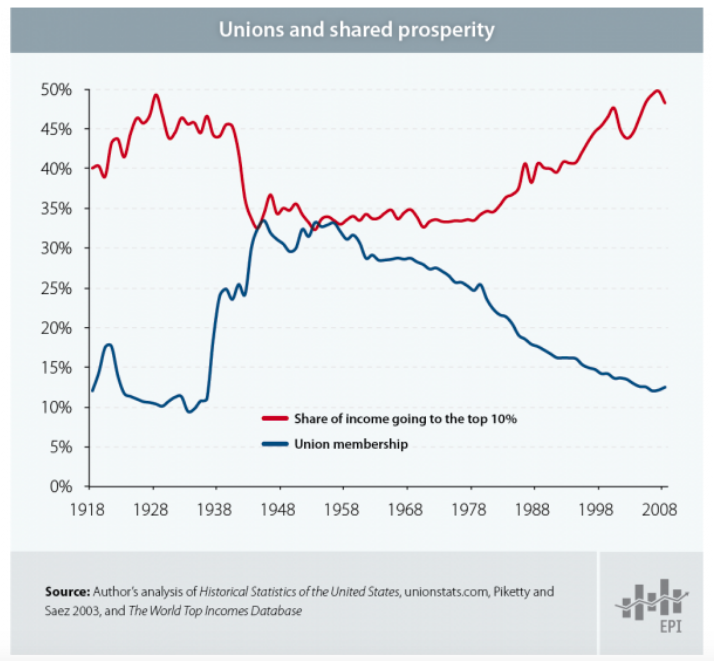

Economists generally agree that unions increase wages, and many say the decline of unions has widened income inequality. A 2011 study concluded that, since 1973, “the decline of organized labor explains a fifth to a third of the growth in inequality — an effect comparable to the growing stratification of wages by education.” This 2016 paper, published by the pro-labor Economic Policy Institute, finds that declining unionization has had an especially damaging effect on the wages of less-educated men.

The influence of teachers unions on outcomes for students may partly alleviate the fears of some parents. Studies in states that curtailed collective bargaining in recent years, like Wisconsin and Tennessee, find the changes have led to lower earnings for teachers, but a 2015 research review by scholars at Michigan State University concluded that “the evidence for union-related differences in student outcomes is mixed, but suggestive of insignificant or modestly negative union effects.”

Recent findings by Cornell University scholars are more dramatic. Studying life outcomes of adults educated in states requiring collective bargaining, they found that “teacher collective bargaining reduces earnings by $199.6 billion in the U.S. annually” and “leads to sizable reductions in measured cognitive and non-cognitive skills among young adults.”

“Taken together,” the authors write, “our results suggest laws that support collective bargaining for teachers have adverse long-term labor market consequences for students.”

4 Most teachers haven’t heard of Janus.

An April survey of 1,000 traditional and charter teachers nationwide conducted by Educators for Excellence, a reform-oriented teachers advocacy group, found that while 85 percent of respondents said unions are essential or important, 78 percent said they had heard “not much” (21 percent) or “nothing” (57 percent) about the Janus case. (Among teachers in New York City, only 24 percent said they had heard not much [13 percent] or nothing [11 percent].)

Given a blitz of union organizing over the past several months and the constant thrum of media stories, these results seems surprising, but they reflect a gap that turned up at least as long ago as 1995. In a poll of its membership that year by the National Education Association, 36 percent — nearly 1 million employees — responded “not at all” to a question asking how involved they were in the union.

5 A ruling against unions will lead to more strikes. Or not.

As some have noted, the spectacular teacher protests beginning in West Virginia in February have a family resemblance. They each occurred in right-to-work states that paid teachers less than the national average and where salaries, adjusted for inflation, had gone down since the Great Recession.

By contrast, Janus will affect states that have better-compensated teachers, higher per-pupil funding, strong bargaining agreements — and stiffer prohibitions against striking.

“Teachers with weaker collective bargaining rights have much less to lose if they strike than teachers in most mandatory bargaining states,” Agustina Paglayan, a political scientist, wrote in The Washington Post. “Ironically, conservative lawmakers who cut back these laws could inadvertently cause even more public-sector strikes.”

Still, although the large demonstrations were not entirely successful, they extracted sizable wage concessions. And they seemed to rise from a broader and infectious ferment of protest, not explicitly partisan and focused on a general good, like the teen anti-gun movement. Teacher walkouts prior to this year were almost unheard of; by the spring, they were standard operating procedure.

“My sense is that the early school year is the classic time for most teachers unions to go on strike,” Michael Hansen of the Brookings Institution said recently. “If anything, we’re entering a prime time for strike season in September.”

6 The next battleground: opting in vs. opting out.

Teacher Ryan Yohn has sued the California Teachers Association in a case that his backers hope to get before the Supreme Court. Yohn argues that the procedure for leaving the union is onerous and designed to prevent members from departing. Teachers should not become members by default rather than by choosing to opt in, he says.

By contrast, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, whose state has the highest percentage of unionized workers, signed into law in April a guarantee that state and local agencies will provide unions with the contact information of new employees within 30 days after they are hired. The unions will be able to recruit employees during work hours for another 30 days.

Cuomo, a Democrat running for re-election this year, didn’t disguise his hope that the legislation could limit Janus’s potential fall-out.

“We are in the middle of a big, big fight nationwide,” he said at the signing.

A similar law was signed by New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy in May.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)