Predicting the Next Wave of Teacher Strikes: Experts See a Whole New Round of Walkouts Come Fall, and a Possible Key Wedge Issue Come Election Night

This spring’s historic teacher uprising, which emptied classrooms and rocked statehouses for three months, just claimed its first political casualty.

In Kentucky’s state legislative elections last week, House Majority Leader Jonathan Shell — a promising young Republican who enjoyed the patronage of U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell — was defeated in the GOP primary by Travis Brenda, a high school math instructor and political unknown. Shell had spearheaded a controversial law to trim teacher retirement benefits, which led thousands of protesters to descend on the state capitol in April.

Captured in Twitter posts and videos on Facebook Live, the spontaneous demonstration unfolded as just one of a relay-style procession of labor actions that hasn’t been seen in recent decades. Beginning in late February, and heading straight into the end of the school year, a torch has been passed from West Virginia to Oklahoma, Arizona, Colorado, and North Carolina: Teachers have walked off the job, pulled on red T-shirts, headed for their state capitols, and extracted significant concessions.

Other than perhaps the groundswell of activism around gun control following February’s Parkland massacre, it is the biggest education story of the year.

But could it become part of the biggest political story of the year?

As Kentucky’s Shell can ruefully attest, primary season is underway for this fall’s midterm elections, when 36 governorships and 87 state legislative chambers will be up for grabs. Even in states that elected President Trump by commanding margins two years ago — including many of those listed above — incumbents now fear the rising blue tide that has already swept away dozens of Republican-held seats.

As a long-standing pillar of the Democratic Party’s electoral coalition, teachers unions could play a decisive role in many of those elections. Though headlines are expected to fade over the summer vacation, a renewal of strikes as September approaches — when parents are left with few options to cope with school closures — could provide a critical pre-election jolt.

“I think what this shows is something much deeper that folks need to be paying attention to, which is the resilience — I won’t even say of teachers unions, but of teachers in American politics,” said Michael Hartney, a professor of political science at Boston College.

Where they’re coming from

Hartney, who is currently writing a book on teachers’ union activism since World War II, said that the conditions have long been ripe for a spasm of labor unrest. The eruption this spring has largely been attributed to years of reductions to teacher pay and benefits as a response to the Great Recession. As teachers have taken on extra jobs to make ends meet, per-pupil funding has dried up in many states as well, resulting in canceled art programs and battered textbooks.

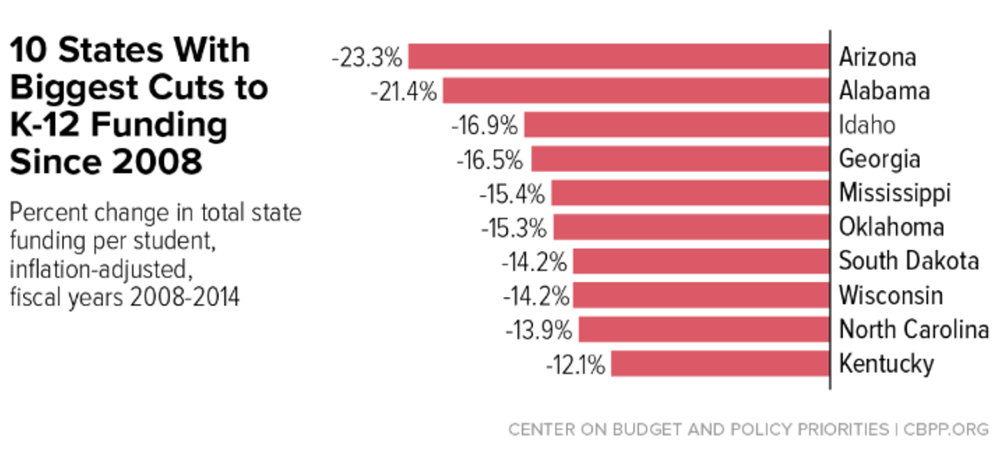

Notably, four of the 10 states where spending has declined the most have also seen teacher walkouts or mass protests.

But Hartney argues that much of President Obama’s education agenda — reforms to teacher evaluation systems, a push for new curricular standards under the Common Core, and a general friendliness toward school choice — helped ratchet up the tension as well.

“Regardless of what you think of the wave of Obama-era education reform policies … it’s simply not a debatable point that teachers, by and large, do not like this vision of school reform,” he said. “If you have stagnant wages, and working conditions at your job are misaligned with what you think they should look like, it’s no surprise there’s going to be a revolt.”

The contours of that revolt have become almost predictable in the days since West Virginia’s teachers first decamped to Charleston. States below the Mason-Dixon line were the early staging grounds for the strikes, especially those governed in whole or in part by Republicans. Labor economist Michael Hansen, director of the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy, published an article last month identifying several common factors that unite states where mass walkouts have occurred.

All of them, he noted, had seen significant reductions in inflation-adjusted teacher pay since the recession. All paid less than the national average for teacher salaries. A majority had seen cuts to per-pupil funding and maintained a state-determined schedule for salaries. Judging by these characteristics, Hansen identified two likely candidates for a teacher uprising. One was Mississippi. The other was North Carolina, which saw 19,000 people swamp the state capitol just a month after the article was posted.

In an interview, Hansen said that the summer vacation would likely do little to cool passions. Twice in the past six autumns, Chicago teachers have won disputes with management by either leaving the classroom or threatening to. And the Supreme Court’s likely ruling in the Janus case, which is expected to deal a harsh blow to the finances of public-employee unions, could only inflame matters further.

“My sense is that the early school year is the classic time for most teachers unions to go on strike,” he said. “If anything, we’re entering a prime time for strike season in September.”

In this case, strike season would also be election season. Could an energized army of public employees, flush with recent successes and largely hostile to the national GOP, turn their attention from education specifically to the ouster of Republican governors, congressmen, and state legislators?

One case study is unfolding in Arizona, where strikers have pushed not merely to boost their own pay but also to reverse severe cuts to education spending more broadly. Even further, many have explicitly militated against a proposal to expand the state’s system of education savings accounts, which offer public funds for parents to pay private school tuition. The initiative was passed last year by Republicans in the legislature and signed by Republican Gov. Doug Ducey, but a corps of dedicated activists — including retired and active teachers — collected thousands of signatures to force a referendum on the program this fall.

Still, Hartney is skeptical that a movement centered on schools will be easily deployed for partisan gain.

“[The unions] have the tailwinds because of Trump, because of DeVos,” said Hartney. “I buy that notion, and certainly Democrats are mobilized this year. But I don’t think teachers get mobilized through the prism of being Democrats. They’re really mobilized around their issues.”

What we haven’t seen before

Dawn Penich-Thacker is the communications director at Save Our Schools Arizona, the group chiefly responsible for forcing the ballot initiative that will allow voters to reject the ESA expansion. By day, she’s a professor of rhetoric at Arizona State; by night — truthfully, whenever there’s free time — she’s broadcasting an argument against private school choice, and drafting any allies she can to the cause.

Inevitably, that means calling on public school employees. While SOS Arizona was busy last summer collecting more than 100,000 signatures to give voters a chance to veto ESAs, it relied heavily on a volunteer force of retired teachers, along with their friends and families. Active teachers, Penich-Thacker said, were hesitant about participating in the campaign, worried that it might impact their jobs.

These days, she says, she is “in daily contact with” the Arizona Education Association and Arizona Educators United, cross-promoting events and giving kudos on Twitter. The SOS Arizona website features pictures of volunteers sporting red shirts, the must-have fashion staple of strike season.

And the coordination doesn’t stop at state lines. Penich-Thacker says that from the beginning, she and her allies have emulated the rabble-rousers who went before in West Virginia and elsewhere. That’s part of the reason the strikes went viral so quickly.

“This cross-state communication is happening because of hashtags,” she told The 74. “The reason the tactics look the same is because we’re all looking at one another’s pictures and saying, ‘Oh, that looks super cool, all that red.’ We’re just stealing good ideas from each other.”

Educators in state after state have moved so quickly, in fact, they’ve often left their own union leadership out of the loop. Walkouts across districts in Kentucky and Oklahoma were conducted largely without the support or approval of union leadership, which was gun-shy about provoking state authorities. The grassroots group Arizona Educators United, which took a leading role in forcing a 20 percent raise in teacher salaries from Gov. Ducey, was started by a handful of teachers in a private Facebook group. Its page now has nearly 50,000 members.

“It speaks to the power of social media,” says the Brown Center’s Hansen. “The environment we’re in now is very different than what has historically been the way of unions leading these actions. Unions certainly have been involved in many of these states, but in quite a few of them, they are not the ones calling the shots.”

Hansen believes that the Republican lawmakers leading most of the strike-afflicted states will be eager to cut deals in the months leading up to their re-election campaigns. But that will require significant new revenue, and most of them won their positions promising fiscal restraint. That bind — lifting taxes, or watching parents tear their hair out come September — isn’t where any politician wants to reside.

SOS Arizona is ostensibly a nonpartisan organization, and its leaders say they will support any office holder who stands with public schools. But that doesn’t mean they plan on staying on the sidelines this November. They’ve already sunk a year of toil into this mission, from circulating petitions in the grueling Arizona heat to fighting off a lawsuit that ESA advocates hoped would invalidate the ballot question. Some Republican legislators have hinted that if it passes, they might simply write a new law next year.

Don’t tell that to Penich-Thacker.

“Another shared goal for us is to elect public-education-friendly politicians so we don’t have to keep doing this,” she said. “Running that referendum last summer, to tell you the truth, was miserable, and we don’t want to do it again next year.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)