‘Is School Choice the Black Choice?’ It’s Time for the Black Community to Band Together to Reform Education From the Bottom Up, Leaders Say at Denver Town Hall

Denver, Colorado

A Friday night town hall on school choice for black families that started with a heated wrangle and impassioned defense of race and choice ultimately conjured resolve to work together as one.

“We all think we’re different animals,” said Democratic Colorado state Rep. James Coleman, a member of the town hall panel. “We’re all the same animal. We are all the same group and organization. We have got to stop acting like we’re all individuals.”

Around 200 families and community advocates attended “Is School Choice the Black Choice?” — an education town hall at the Potter’s House Church of Denver led by broadcast journalist Roland Martin. More than 200 others tuned into a live stream online. The event was the sixth stop in a 10-city tour hosted by Martin and The 74. The events aim to engage black families and stakeholders on issues of educational equity, student achievement and parent involvement.

The animated discussion Friday night was not unlike the conversation in Atlanta in February, where Martin held the second of his school choice events. There in Georgia, panelists implored their fellow black parents and advocates to work together, rather than fight over the politics of school choice, because they “are on the same side.”

Much of the school choice bedlam has to do with incentives and interests — critics rebuke choice for taking tax dollars from traditional public schools and, in some of its forms, for being able to operate with less accountability for student outcomes, among other issues. Advocates are a chorus of the “one size does not fit all” philosophy — that school choice is critical to families’ abilities to send their children to the schools that most fit their individual learning needs, particularly for children from low-income backgrounds or students of color.

That rift was palpable Friday night in Colorado.

“If schools aren’t working for your child, you don’t just keep taking them there and hope it’s going to get better,” said Parents Challenge Executive Director Deborah Hendrix. “When I talk about choice, we make choices in everything else — what car we drive, what house we live in, what clothes we wear, what restaurant we go to — so why don’t we have the same choice in how we educate our children? As a parent, this is my No. 1 asset — my children — and I need to make sure I’m doing right by them regardless of the system.”

Joining Hendrix and Coleman on the panel were Jennifer Bacon, a Denver Public Schools Board of Education member; Papa Dia, founder and executive director of the African Leadership Group; Wisdom Amouzou, co-founder and executive director of Empower Community High School; and Hasira “Soul” Ashemu, executive director of Breaking Our Chains.

Ashemu pushed back: The very system of choice that Friday’s town hall was advocating for in the black community was one born out of segregation, he said. Although the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board declared “separate but equal” education unconstitutional, the decision lacked an explicit mandate for integration, so many districts and states conjured ways to dodge the court’s ruling.

Two years later, Sen. Harry F. Byrd Sr. of Virginia had gathered more than 100 signatures from Southern lawmakers supporting the “Southern Manifesto,” which defied school integration and created a foundation for a set of laws, known as Massive Resistance, that ignored the Supreme Court’s decision. In many cases, the resistance allowed districts and states to shutter schools altogether rather than integrate, or to pull public funding, which forced localities to close schools — and that money was then reallocated to white students to attend segregated schools of their choice. And thus, Ashemu noted, the concept of school choice was born.

But, Martin challenged, “You can’t show me a system in America white folks didn’t create.”

So, Bacon said, it’s time for a culture shift.

“Sure, we have choices; sure, the school has the data for my kid to go to college, but someone else decided for me that this is what my kid needs. The families and the students who have to make the choices aren’t the ones deciding what they are,” she said. “We haven’t created a system that has leaned into the freedom of defining what choice is. People aren’t liking those choices because they haven’t had a hand in building what it is. They really don’t get to create the menu. It doesn’t feel like a choice for them.”

In Denver, segregation persisted for years after Brown — until a 1973 decision in Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver found in favor of the plaintiff families suing for equal treatment and declared that the school board was guilty of a deliberate segregation policy. In response, DPS started a busing program to integrate schools.

In Colorado today, 250 charter schools serve more than 120,000 students — 13 percent of the state’s public school enrollment, according to the Colorado League of Charter Schools. That’s twice the national proportion. Across the country, 3.2 million students attend 7,000 charter schools, representing about 6.5 percent of the country’s nearly 50 million public school students.

Colorado’s charter school law was enacted in 1993, and after numerous updates, it is now ranked the second best in the country — behind Indiana — by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. The alliance issues an annual report that ranks states based on their charter laws “to figure out which states are creating the conditions for high-quality charter schools by providing, among other things, flexibility, funding equity, non-district authorizers, facilities support, and accountability.”

It praised Colorado for allowing an unlimited number of charter schools and offering notable accountability and autonomy to charters — although full-time virtual charter schools still lack accountability. While the state has made progress in providing more equitable funding and facilities to charters, the report states that work remains.

And although Denver has been heralded as a leader and pioneer for some of the country’s most innovative and successful non-traditional schools of choice, a resistance has started to form in recent years. Now, a pivotal school board election next month could “flip the board” from a group of choice-friendly leaders to one that seeks to place a limit on the number of charter schools in the district.

Charters aren’t the only form of choice in the state. Colorado’s Public Schools of Choice law allows students to enroll in districts for which they are not zoned — otherwise known as open enrollment. The state also has more than two dozen magnet schools educating more than 12,000 students. And for four years, Colorado operated the Douglas County Choice Scholarship Pilot Program, a voucher program that offered 500 tuition vouchers for students to attend private schools — including religious schools — using public dollars. The Colorado Supreme Court suspended the program in 2015, declaring it a violation of an amendment to the state constitution that bars state support of religious organizations.

After widespread feedback about poor treatment of black students and teachers in DPS, the district in 2016 commissioned a study that interviewed educators about their experiences. The results were striking. More than 90 percent of those surveyed said that racism was rampant across the district. Among the other findings: Nonblack teachers don’t expect black students to excel academically, many teachers simply fear black students, and the district hasn’t provided resources to black students at the same rate of growth as English language learners.

“African-Americans in DPS are invisible, silenced and dehumanized, especially if you are passionate, vocal and unapologetically black,” one educator said in the report. “We can’t even be advocates for our kids. It feels a lot like being on a plantation … there is a lot of fear and black folks are pitted against each other.”

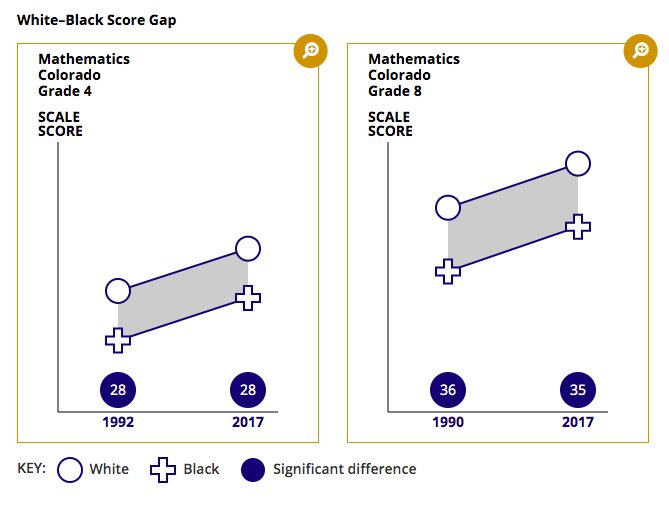

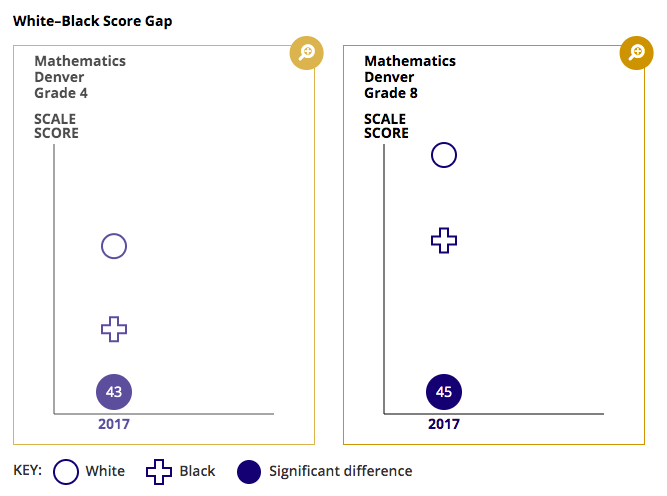

What’s worse, overall, Colorado’s achievement gap — the difference in academic outcomes between ethnic groups — has not closed in a quarter century, according to student scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, commonly known as the Nation’s Report Card. In 2017, the first year in which NAEP broke down scores by major districts, Denver’s achievement gap was among the widest in the country.

The situation is so dire in Denver that the district’s school board unanimously passed a resolution earlier this year requiring all DPS schools to devise a plan to boost black student achievement. (Bacon led the initiative.) For black students in DPS, 1 in 5 are proficient in math and reading on state exams, Bacon said Friday.

“One of the biggest problems is that we sometimes do want to accept that we are not doing well,” Coleman said. “It’s not beating yourself up; it’s talking about the harsh reality that our children are not being served well. … We have to be innovative in how we do that work, but we can’t accept failure in any capacity.”

But, Coleman noted, that “harsh reality” is also that it’s not necessarily about politics or school structure. Neither of the major political parties, nor traditional public schools or charter schools, are serving black students well, he said, adding that it’s up to the parents and the existing community organizations to put aside the 10 percent they disagree on so that they can work for the 90 percent that they do agree on.

That also means motivating more parents to be active — by taking on leadership roles in education or running for school board positions despite the fact that the jobs don’t pay or that they think they may not have time, Hendrix, of Parents Challenge, said.

“A lot of times, we’re not at the table; therefore, when they’re looking for many of us to serve in those roles, there are one, two,” she said. “We have got to be willing to be in the schools designing the curriculum and running the programs.”

That all comes back to putting aside differences so that the black community is not internally fighting each other, Coleman said, and to support education leaders like Amouzou — whether or not they see eye to eye on the politics of choice — because schools like his are educating black students the way their parents want them to be educated.

At Amouzou’s Empower Community High School, a charter school in Aurora, Colorado, 14 of the 16 staff members identify as black or Latino. The executive director, principal and board chair are all black. (Extensive research has shown that students perform better when they are educated by those who look like them.) It is also at Empower that ninth-graders are reading about quantum physics and studying college-level research on social justice.

Dia recognizes that a culture shift that involves widespread black leadership and equitable education is not going to happen overnight.

“What is left to parents to do in the meantime?” he asked. “We all know that we cannot fail our kids and we need to figure out a way where parents get the power back to them. And the only power that they have is to be able to pick. It’s obvious. This country that we live in, everything happened at the top and came down to the bottom. It’s time for us to start it at the bottom and build it to the top.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)