Returning to the Site of Their Segregated High School, Student Strikers Recall Their 1951 Protest and Urge That Its Role in Brown v. Board Not Be Forgotten

Farmville, Virginia

The United States of America was not founded nearly 250 years ago with the Declaration of Independence, says a former Virginia newspaper editor.

“This country is still being founded, it certainly was not founded in 1776,” said Ken Woodley, former editor of over two decades for the Farmville Herald. “This place, more than Independence Hall, was the birthplace of America.”

Woodley was referring to the spot where he was standing, the former R.R. Moton High School, where a 1951 student strike led to the inclusion of more than 100 Virginia students and families as plaintiffs in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. The brave stand taken by the student strikers to protest a grossly unequal public school system, Woodley said, gave actual meaning to the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that all men are created equal.

Woodley made his remarks at the Robert Russa Moton Museum, the building that once held the all-black segregated high school in Farmville, Virginia, where dozens of community members gathered Saturday evening to partake in a panel discussion featuring former plaintiffs — including the Moton student strikers — in the 1954 landmark case Oliver Brown, et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka (KS), et al., which declared “separate but equal” unconstitutional.

The 74 interviewed the former student plaintiffs in their Farmville homes ahead of the event and visited key sites with them. See the photo tour here.

Saturday’s event was the second in a nationwide tour commemorating the 65th anniversary of the historic decision and was co-hosted by the Moton Museum, the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence, and Research, the Walton Family Foundation and The 74. The series celebrates the untold stories of the hundreds of plaintiffs whose narratives were lost behind the “et al.” of Brown, et al. The first event took place in Washington, D.C. earlier this month. The tour is headed to Topeka, Kansas, on Nov. 12.

Of those forgotten Brown cases, Virginia’s Davis v. County School Board was the only one that was student-led. But little of that history makes it into textbooks, said Cheryl Brown Henderson, founding president of the education foundation that bears her family name and the younger daughter of named plaintiff Oliver Brown.

“We’ll get a student from Virginia wanting to know all about Topeka, and my response is, ‘What about your case?’ And they won’t know that Virginia was a part of Brown v. Board, so it’s supremely frustrating for us,” she said. “We’re doing our students a disservice by not teaching what actually happened.”

Sharing the panel with Brown Henderson in Farmville Saturday were three of the Moton High strikers and Davis case plaintiffs — Joan Johns Cobbs, Joy Cabarrus Speakes and John Stokes — and Cainan Townsend, director of education and public programs for the Moton Museum.

Moton High, in largely rural Prince Edward County, was about 70 miles west of Richmond in southern Virginia. The school was intended to house 180 students, but its student body grew to more than 450 by 1951. Students who didn’t fit in the main building took lessons in tar paper shacks heated by potbelly stoves, and the school lacked textbooks and facilities like an infirmary and teachers’ restrooms. The school’s auditorium also served as its gymnasium and cafeteria as well as overflow classroom space. Many of Moton’s students traveled umpteen miles, past modern and well-equipped all-white schools, to get to and from school each day.

On April 23, 1951, Moton student Barbara Johns — fed up with district officials’ ambivalence toward the black community’s demands for better and more equitable schooling conditions — orchestrated a meticulous plan that lured Principal M. Boyd Jones out of the building and gathered the student body in a surprise assembly.

“Then, on this very stage, these curtains opened, and I saw Barbara standing there,” Joan Johns Cobbs, Barbara’s younger sister, recalled Saturday.

As Joan slid slowly deeper and deeper into her seat on that April morning to pre-empt embarrassment from her sister, Barbara made an impassioned speech against injustice, calling on her more than 450 classmates to protest until their demands for a new building and equitable schooling conditions were met. The student body walked out of school after that assembly, beginning a two-week strike that led NAACP attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill to file Davis v. County School Board on behalf of the students a month later.

Also folded into Brown were Delaware’s Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart, South Carolina’s Briggs v. Elliott and Washington, D.C.’s Bolling v. Sharpe. Although Briggs v. Elliott was the first to arrive at the Supreme Court on appeal, it is widely believed that Brown became the lead case given Kansas’s position in the middle of the country. The court saw it as an opportunity to take the issue of segregation in education out of the South and catapult it onto a national platform.

Because “everything is money,” Brown Henderson said, the “next frontier” in raising awareness of this richer history is to reach out to state leaders who purchase educational resources to use their buying power to impress upon textbook companies the need to correct lessons about Brown v. Board.

“What we really have to do is speak up and use our voice to make sure that we don’t go backwards, and that we continue to go forward,” Cabarrus Speakes said. “I hope that everyone remembers to use your voice and make a difference wherever you can, because we still have a ways to go.”

In Virginia, advocates like Townsend, the museum’s director of education and public programs, are working together to submit a series of curriculum proposals to the state next year that would be “more inclusive of all Virginians” and teaches Brown v. Board in more detail.

“[We’re submitting a curriculum change because] you can’t have textbooks that don’t go along with that curriculum,” Townsend said. “So hopefully, you’ll find textbooks that are more accurate.”

But in the very state that led the charge to desegregate schools in America, history is beginning to repeat itself. In 2010, 6 percent of Virginia schools were “intensely segregated,” according to a 2013 report by the University of California, Los Angeles’s Civil Rights Project. That figure was just half that — 3 percent — two decades prior in 1989.

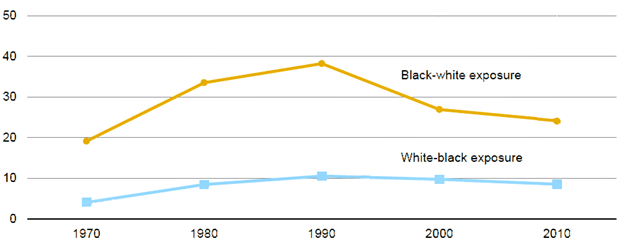

And while major metropolitan areas are becoming less segregated across the country, black-white exposure in schools has plummeted since 1990. In 2010, the student body of the average white student’s public school was about 10 percent black — about the same as in 1980, according to research by Grover J. Whitehurst, a fellow in the Center on Education Data and Policy at Washington, D.C.’s Urban Institute. But the average black student’s public school had a smaller enrollment of white students than similar institutions did 30 years prior.

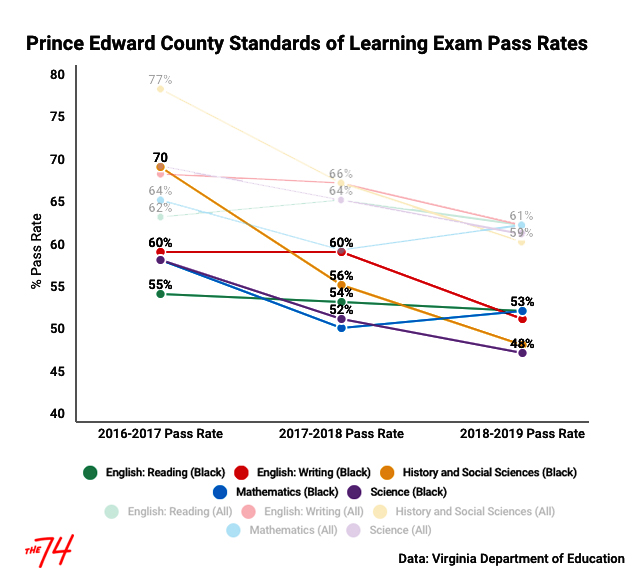

In Prince Edward County, nearly a quarter of the population lives below the federal poverty line and more than one-third of the student population identifies as black. Black student performance on annual state exams has for years trailed outcomes across all racial groups, but scores in almost all subjects continue to dive.

“What we’re experiencing now tells you how tenuous those [Brown v. Board] accomplishments are, which means you can’t stop. We have to pass the torch on to the others coming up behind us. We age out in terms of energy and even remembering and all the things you need to do this work,” Brown Henderson said. “There’s so much work to be done to recognize what’s happened in our country to make the change that our young people take for granted. But it has to be done.”

Although the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown overturned Plessy v. Ferguson and declared segregated education illegal, it didn’t explicitly give a mandate on integration, and many all-white schools ignored the decision. So in a second case in 1955, Brown v. Board of Education II, the country’s highest court handed down a ruling that ordered states to desegregate schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Still, Southern politicians continued to push back. The state that spearheaded the movement for educational equity was also the one that led the fight against it. By 1956, Sen. Harry F. Byrd Sr. of Virginia had gathered more than 100 signatures from Southern congressmen backing the “Southern Manifesto,” which opposed integrated schools and laid the groundwork for a set of laws that resisted the Supreme Court’s mandate. Those regulations, which became known as Massive Resistance, had varying degrees of impact on Southern states.

In Virginia, rather than desegregate schools, the state chose to either shutter them altogether or pull funding from districts, which forced localities to close schools. For the five years between 1959 and 1964, children in Prince Edward County — a so-called “lost generation” of children, as the locals consider them — had no formal education. The Quaker community — the Religious Society of Friends — did what they could to raise funds and help place some children in other states for schooling.

It took another legal effort, partially led by then-U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to compel Prince Edward County to reopen its schools in 1964. That year, just five percent of students in Virginia were enrolled in desegregated schools.

“All of you represent the words that were written in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, words that the men who wrote them and signed them did not believe,” Woodley, the former newspaper editor, said to the Brown plaintiff panelists Saturday.

“You all gave me faith in the country I read about in Munford Elementary School in Richmond. It turns out I was reading a whole lot of lies, but you all took America at its word. The good thing that this country did with ‘all [men] are created equal’ is it set the bar high; you and your families took hold of that bar and raised this country up.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation, a sponsor of the event, also provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)