State Tests at Risk During Pandemic: Low Turnout for ‘Required’ Ohio Reading Test in Cities Suggests COVID-19 Could Keep Kids Home

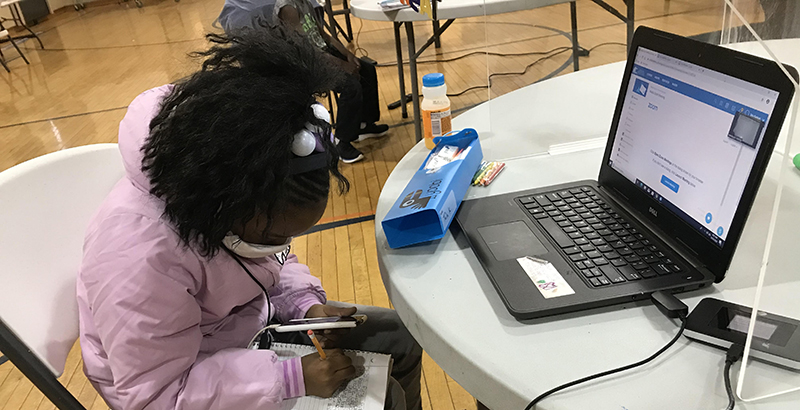

Across Ohio, school districts are attempting to comply with a state law requiring all third graders be given state reading tests — even in the middle of a pandemic.

But few parents in Ohio’s urban districts have opted to send their kids to school to take an exam that has no bearing on student grades or promotion amid rising COVID-19 counts and widespread school closures.

It’s a trend that suggests there could be trouble in the spring when Ohio and schools across the country give their full slate of state tests that are sometimes used to determine grades, promotion or graduation and are typically used to rate schools and districts.

Chad Aldis, head of Ohio effort\s of the right-learning Fordham Institute which has urged Ohio to give the upcoming spring tests to gauge how much students are falling behind, is now pessimistic about testing if COVID rates stay high.

“I don’t think you’re going to have state assessments if kids aren’t back in school a couple days a week,” said Aldis.“I just don’t see it happening.”

The emerging pattern also suggests that rural and suburban districts where COVID rates are low and schools are open have had few problems in giving the test.

In Ohio’s cities it’s a different story — where more parents are keeping kids home on test days than during the much-publicized “opt-out” movement when new Common Core tests started across the country in 2015.

In Cleveland, for example, only 136 of the city school district’s 2,700 third graders are willing to come to school to take the test next week.

In Akron, less than an hour to the south, only 215 of 1,500 third graders are taking the “required” test. Toledo, which has some students attending school and others online, is having no trouble testing students who are attending school in person, But only 26 of the 200 third graders whose parents chose to have them take classes online l will come in for the tests.

And in Dayton, about 85 percent of third graders are taking the tests, a much better rate, but still well below the 95 percent federal target for spring tests.

Cleveland schools CEO Eric Gordon, whose students have been taking online classes all school year, has expressed frustration in recent weeks over having to open schools just for tests, then find teachers to proctor exams and plan bus routes to bring students to school.

Dayton Superintendent Elizabeth Lolli has raised concerns about the reliability of testing students when COVID rates are high and communities are rated as red – high risk – in the state’s COVID warning system.

“Bringing students back (for tests) in counties that are red and parents are saying ‘I’m not bringing my child in to school to be tested,’ to assume that the state testing mechanism…is going to show us what we need to have and it be reliable and valid is inappropriate,” she said.

How much state testing should happen this coming spring, or if any should happen at all, has been debated across the country since March when the virus swept across the country and shut schools down. Canceling tests in the spring was an easy call, since they have to be given at school in front of teachers and schools were all closed.

U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos waived federal testing requirements in the spring, but has denied requests from states like Georgia and Michigan to waive requirements for spring of 2021. She has told states not to expect any.

Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has not taken a public position on waivers.

Ohio’s testing debate this summer and fall followed the historical and national pattern. Democratic legislators, teachers and urban districts called for Ohio to halt all state tests other than those required by federal law. They also wanted Ohio to ask the U.S. Department of Education to ask DeVos for a waiver.

But Republican legislators want to keep the tests, even if results would be flawed, to have some measure of how much students are falling behind during the pandemic.

“Some kids have not been in the classroom since last March,” said State Rep. Don Jones, chairman of the Ohio House Education Committee. “Schools really need to know where these kids are.”

Ohio Federation of Teachers President Melissa Cropper said districts already use diagnostic tests that already show how far kids are falling behind and that teachers can use to help kids catch up.

She also worried that tests cannot be given accurately, even if remotely.

“There is just no way we are going to have any reliable data come out of the testing in the COVID-19 situation,” she said. “Unreliable data is more dangerous than no data at all.”

With the sides not reaching agreement, a bill to halt or reduce tests stalled in the Senate committee a few weeks ago and legislators left Columbus to campaign for Tuesday’s election.

There’s also pushback to coming in for tests this fall in Florida, even though that state’s fall kindergarten diagnostic and high school make-up tests are optional. Stephen Pruitt, president of the Southern Regional Education Board, a 16-state compact of educators running from Maryland to Kentucky and Florida to Texas, said he expects more controversy as spring tests near.

“I think the biggest part that’s been hard about COVID is everything feels like you’re looking into a crystal ball,” Pruitt said. “If there’s not a significant change by the time we get to next spring, it’s going to be an issue that every state’s going to have to deal with.”

Though Ohio has time to address spring tests after the election, the legislature took no action on the fall reading tests, a failure State Sen Peggy Lehner, chair of the state Senate Education Committee called “very unfortunate.”

The fall tests are given as part of Ohio’s Third Grade reading Guarantee, a requirement that students score close to proficient in reading before they can advance to fourth grade. Students that meet the score on the fall test are cleared to advance, but most students need the spring or even summer tests to pass.

For them, the fall reading test allows teachers and parents to know how much they have to improve over the school year. Because the legislature already waived reading test score requirements for this school year, the tests have even less impact on students.

The Ohio Department of Education is giving schools mixed messages about how to handle the tests. It’s not canceling them, saying it can’t change state law, but it’s also telling districts that safety is the top priority.

Gov. Mike Dewine has not taken a public position on the tests, but has said that classroom activity does not seem to be causing COVID spread among kids. Most is happening from less controlled, out-of-school activities.

“Does he think it’s safe to go to school and take a test? The governor says yes,” said spokesman Dan Tierney.

One solution: Find a way to have students take the tests remotely. Pruitt said some of his states are exploring that option. Ohio is too, according to the Ohio Department of Education, but no details are available yet. At the same time, there are worries about how accurate home tests would be when students might receive help from parents or other sources.

Lehner said she hopes the fall tests offer “some clue as to how far kids have slid since last winter.”

“We’ll get some idea,” she said.

But as the 2015 opt-out movement showed, states have no legal authority to force students to take state tests. There’s even less power now when safety is at stake.

“You can’t tell a parent whose child is learning from home because their school will not open because it’s not safe that they need to send a child in to school to take a test that has no real significance,” said Lehner.. “They just aren’t going to do it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)