Poorest Students Avoided COVID Slide on NWEA Tests, Cleveland Data Show

Cleveland students’ scores on national diagnostic tests suggest that poor and minority youngsters nationally may have also avoided the massive COVID slide predicted last spring.

The testing organization NWEA created a buzz last week when it released data from its fall tests of 4.4 million students nationwide showing the learning loss under COVID, so far, seems far lower than many predicted.

A big caveat was that results came mostly from white and affluent students, while poor, minority and disadvantaged students were underrepresented. The pandemic’s impact, NWEA cautioned, could be much worse for them.

But judging by Cleveland’s numbers, the impact hasn’t hit harder, it hit about the same.

The Cleveland school district offers a look at the students most left out of the data from NWEA, previously known as the Northwest Evaluation Association. More than half the Cleveland school district students are Black and 100 percent of students receive free lunch, the main indicator of student poverty.

Cleveland also has the highest levels of childhood poverty in the country.

But Cleveland students largely met the national patterns, according to test scores and a district analysis obtained by The 74. The results have limitations, however, just like NWEA’s national results do. About 5,000 fewer Cleveland students took the tests this fall than last year. And district officials had some concerns about tests taken remotely while schools are closed.

When comparing this year’s scores to last year’s, declines were generally small. For instance, seventh graders this year earned a 205.3 English score this fall, compared to 205.6 for last year’s seventh graders.

In a few cases, point drops were larger. Sixth grade math was a rough spot, with this year’s sixth graders scoring 201.5 compared to the 204.9 for last year’s sixth graders.

But every class cohort, like third graders last year moving to fourth grade this year, saw slightly improved scores this fall over their own scores from last fall and last winter.

The district considers the results “mostly flat.”

They did not regress over the spring school shutdowns, over summer break or so far this year, even with classes entirely online.

“While these results indicate significant risks to vulnerable populations of students and [the need for] intensive supports for larger numbers of students, they are better than what we were expecting,” the district’s research staff concluded in a report.

While Cleveland students are the exact demographic underrepresented in the national data, NWEA cautioned not to read too much into Cleveland’s results.

“I am not sure it’s possible to say the pattern observed in Cleveland generalizes to the entire poor, minority population, but it is encouraging that their results match the national trend,” said NWEA researcher Megan Kuhfeld.

The district also has concerns about the accuracy of the results, particularly in the first and second grades, because of “over-engaged” parents while students took the tests remotely. Cleveland officials are discounting scores from those grades as NWEA did nationally, because results came in higher than last year.

“Teachers reported having parents who interfered with their child’s testing by helping them with the answers,” the district reported. “Teachers reminded these parents to refrain from providing help, but some parents remained insistent. Some teachers suspended testing (per district instructions) and some teachers were uncomfortable suspending testing due to possible parent backlash.”

Cleveland Teachers Union President Shari Obrenski also heard those complaints.

“Parents were trying to help their students do well, not fully understanding that those tests are a gauge of where we need to help,” she said.

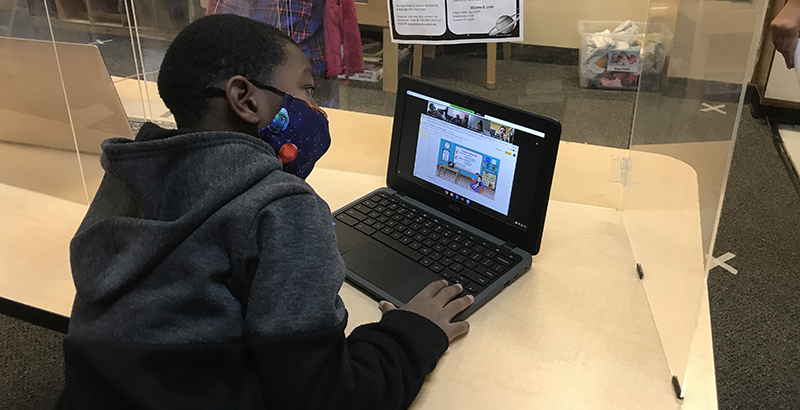

Teachers also reported that students often turned off their laptop cameras and could not be monitored, sometimes because they did not have the bandwidth to run tests and the cameras at the same time. That meant that teachers could not make sure students weren’t looking up answers.

The effects of small numbers of test-takers seem to show up in Cleveland’s results for 9th and 10th grades. Though students in those grades scored higher this year than last year in both math and English Language Arts, fewer students took the tests than in other grades, suggesting that low-scoring and disengaged students are not reflected in the results.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)