How Schools Are Keeping Families Afloat During the Pandemic: COVID Shut Cleveland’s Classrooms, But Not the Wraparound Services So Essential For Both Parents and Students

Teachers gathered outside Lincoln-West High School earlier this month had a flurry of questions for Crystal Butchart as she walked up to the stacks of produce boxes at the edge of the parking lot.

“How many children are under 18?” she was asked about her family. “How many adults over 60? Any other adults?”

Within moments, volunteers at the school’s monthly produce giveaway had tallied her needs and started carrying boxes of bananas, apples, oranges and lettuce to her car. Butchart’s 10th and 12th grade sons would have plenty to eat while shut out of school and taking classes online at home because of COVID-19.

“Getting the produce is healthy for them and it’s so close,” said Butchart, who lives in the neighborhood. “The kids are so big and they’re eating so much out of the house because they have to stay at home.”

The produce handout is part of the Cleveland school district’s attempt to keep its growing work to offer so-called “wraparound” services to students and families alive through the pandemic. In pre-pandemic times, the efforts relied on full-time support staff working in schools to see students every day, learn of the needs of families and connect them to services like health and dental care, mental health supports, tutoring and even legal advice.

The school shutdowns in March and the district’s need to keep schools closed all this fall shut down the chance to see kids every day. But they didn’t stop services.

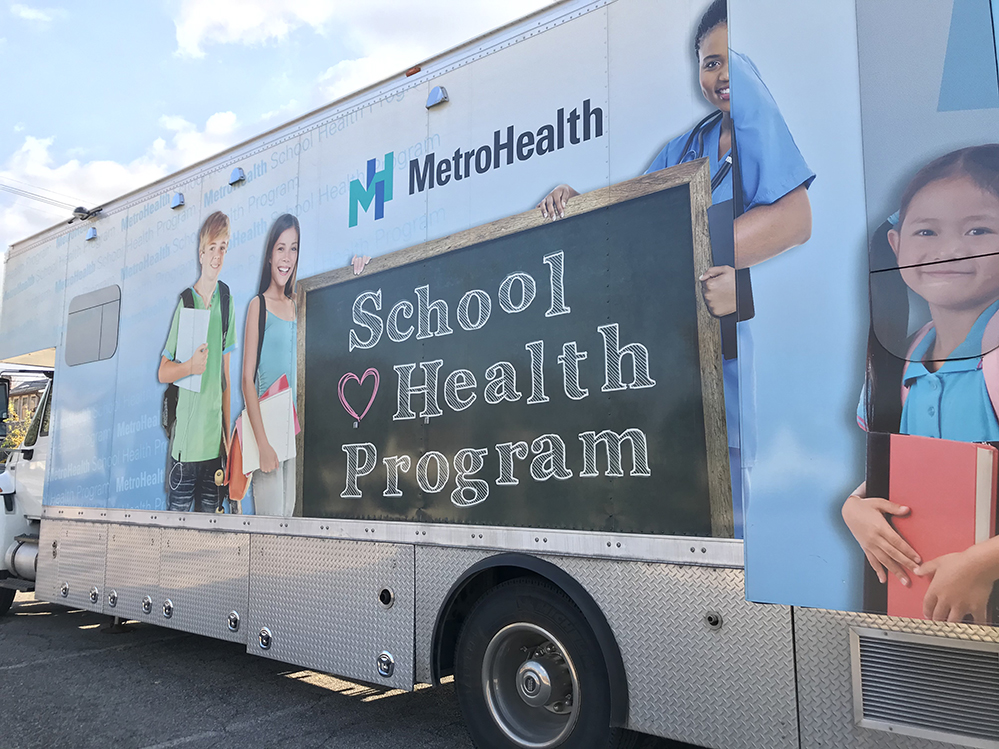

Service coordinators now reach parents by texts or Zoom. Mobile health clinics have started again. And coordinators are still directing parents to help with rent and tenant rights, and even dropping off items like toothpaste and toilet paper at student homes.

The work has even grown during the shutdown. What started in 2014 with services in 17 schools has now expanded to 52 of the district’s 100 schools, 22 added just this fall.

And many community organizations that used to provide after school programs as part of wraparound efforts are now running daytime learning centers, sometimes called pods or hubs, where students can take online classes while parents work.

“How can we expect kids to perform their best academically if they don’t have enough to eat at home or their families are facing eviction?” asked Norah Leahy, who organizes services for Lincoln-West. “We’re here to work with families and with the school as a team. Our ultimate goal is to support every family in each and every way that family needs.”

Leahy was hired more than a year ago as part of the Say Yes to Education college scholarship program that expanded into Cleveland two years ago. Along with giving scholarships, Say Yes requires schools to provide wraparound supports so students can learn more and be better prepared for college. Jon Benedict, spokesman for the Cleveland chapter of the Say Yes,said that maintaining services during the pandemic and limiting damage from it, is crucial for the city and its students to rebound later.

“Keeping families afloat and keeping kids learning is going to make a difference in the long run,” Benedict said. “It’s the thing that will differentiate Cleveland from a lot of other large economically challenged school districts.”

Cleveland’s use of social supports in schools is partly inspired by the national “community schools” movement, which has seen schools in New York City, Baltimore, Portland and central Florida treat schools as community service hubs for helping struggling families. By eliminating some of the obstacles that distract students from learning, the schools have seen some academic, attendance and behavioral gains.

Such supports are also being viewed as crucial to schools recovering from the pandemic by organizations like the Brookings Institution and the Learning Policy Institute. The latter is run by Linda Darling-Hammond, the Stanford professor who is now president of the California state school board and is leading President-elect Joe Biden’s education transition team.

Wraparound services are also supported by both national teachers unions, the National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers. Ohio Governor Mike DeWine put money in the last state budget for such services in schools.

Say Yes to Education, which operated in Syracuse and Buffalo, N.Y., as well as Greensboro, N.C., before launching in Cleveland in 2019, accelerated wraparound efforts here before the pandemic and has stayed focused on continuing them in all of its cities.

Say Yes officials in Buffalo and Greensboro, said they saw no choice but to continue offering services during the pandemic.

“We’re serving the children we were serving before, and more in many cases,” said Say Yes Buffalo Executive Director David Rust. “But I don’t think us or any city has a silver bullet answer to this.”

In a typical year, full-time staff at the schools help organize after school, summer and weekend programs for students, then serve almost as social workers, helping families with food, clothing and housing needs through non-profit and government agencies in the community.

When COVID forced schools to close in March, the daily contact with families was cut off. Afterschool tutoring, chess, soccer, poetry and arts programs were canceled. Summer camps were canceled, with a few exceptions.

Support staff had to adjust quickly.

“The need for our services increased, but the biggest challenge was getting in touch with families,” said Jerrald Goodloe, who organizes services at Michael R. White elementary school. “We knew that we needed to step up. We knew that families needed us. But for a short period of time there was a breakdown in communication. We were so used to having face to face contact.”

Sometimes teachers had phone numbers. Sometimes staff had to search social media or ask other students how to find their friends. Eventually, support specialists learned that parents weren’t often on email. Cleveland has the greatest percentage of families in the nation without internet connections. So calls and texts work better.

Families were losing jobs, Goodloe said, and then losing cars and facing eviction. Though a moratorium on evictions was soon ordered, families needed help understanding it and standing up to landlords, he said, so families were referred to the Legal aid Society of Cleveland, which helps families as part of the wraparound services.

Even this fall, half of Legal Aid’s referrals from the district are about evictions, said Executive Director Colleen Cotter. She expects that to rise when the moratorium ends Jan. 1. Immigration cases are also another constant worry.

There continues to be demand for food and household goods in a city that has the highest child poverty rates in the country, by some measures. Michelle Dowd, who oversees services at Cleveland’s Adlai Stevenson elementary school, has been stopping by a few dozen student homes every Friday to drop off bags of toothpaste, deodorant, shampoo and toilet paper since the spring.

“Even though I am able to help a lot of families, there are 512 kids in our building and I know I’m not nearly touching that many children,” said Dowd. “I’m sure there are so many more families that are in need.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)