Helping Students With Remote Learning — By Also Aiding Their Parents With Wraparound Services: How One Texas Community Center Is Helping Families Facing Impossible Choices

When parents drop off their kids at the Guadalupe Community Center on San Antonio’s West Side, program manager Manuel Garcia doesn’t want them to feel as if they are making yet another tough choice in the middle of the pandemic.

In the past few months, as the pandemic has dragged on and jobs have either disappeared or had their hours cut, more families are choosing between groceries and medications. Between paying electric bills or rent.

Now that school is in session, remotely, kids need Wi-Fi, log-in help, quiet workspaces and, for younger kids, constant supervision. Providing any of those things will cost money and time that have to come from somewhere else.

Garcia wants the program he manages to provide a safe place where the entire family will be given the support and routine they need to thrive during remote learning — an easy choice, and a high-quality one.

At the center, while parents are picking up or dropping off their kids, they can find resources to help ease the other trade-offs they’re often forced to make. They can get extra clothing, food, counseling and help with utilities.

“We’re securing these families with wraparound services,” Garcia said. “We become a second family.”

Family support is more essential than ever — and harder to come by — now that kids can’t go into school buildings with counselors, caseworkers and nurses.

The pandemic has emphasized the connection between stability at home and engagement in school, and places like the Guadalupe Community Center are uniquely set up to help in the city’s poorest zip code, 78207, where the effects of the pandemic are mounting. The “day school” run by Garcia is just one of the 40 programs operated by Catholic Charities Archdiocese of San Antonio, and parents can connect to all of them with the help of caseworkers at the center.

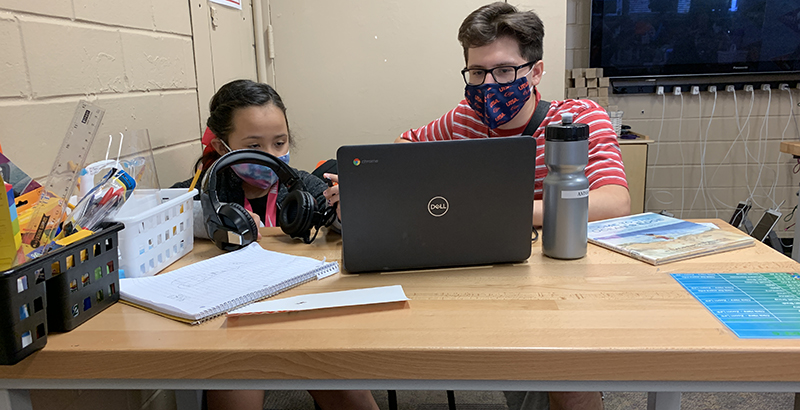

Around 30 K-12 students spend their days at the center, where each appropriately spaced, assigned work space has hand sanitizer, cleaning wipes, and the student’s usernames and passwords for distance learning taped to the corner of the desk. They get meals and snacks, homework help, school supplies, reliable internet, and access to several adults whose job it is to make sure they are logged on and making progress.

Similar programs around the city cost around $140 per student per week, Garcia said, based on his research. Catholic Charities offers them for free. He knows that for every cost, something at home would have to give.

Parents living in poverty are used to making tough calls, said Catholic Charities caseworker Debra Martinez. Many must choose which bills to pay from month to month. They are familiar with the subtle hierarchies of needs within what middle-class Americans consider essential.

In the best of times, the trade-offs make parents feel bad, said Martinez. “Sometimes parents want to hide that from their kids, but it’s very noticeable [to the kids].”

The pandemic is making this worse.

Earlier in September, Catholic Charities had to move its food pantry from a room at the Guadalupe Community Center to another facility nearby, as they went from serving 95 people per week to 1,100 per week.

The pandemic has also carried new costs. Providing internet for remote learning has been “one of the biggest stressors for the families that we’re serving,” said Lizzy Perales, vice president of programs for Catholic Charities.

Some households that started the pandemic with internet access have lost it as months of furlough or unemployment stretch on. Many of the households in the neighborhood are multi-generational, and multiple sibling groups might live in one house. Having them home all day strains food and utilities budgets.

But parents and grandparents aren’t willing to send their kids off to dangerous or stressful circumstances just to get them out of the house.

Knowing this, Catholic Charities wants parents to feel good about dropping their kids off at the day school, like they are giving the kids a leg up.

“It’s not just a safe place where they come and get meals; they actually are getting this huge benefit,” Perales said. Kids get access to reading material and extra classes similar to what they might get in private afterschool programs, she said.

Kids whose parents have more money have access to that kind of tutoring and enrichment, Garcia said. “These kids deserve the same.”

In non-pandemic circumstances, as many as 70 to 80 students can attend afterschool programs at the center. Staff members check grades, go to parent-teacher meetings and call the school when students aren’t getting the services or academic support they need.

“Our center has discovered three dyslexic students who had slipped through the cracks,” Garcia said. Schools used to find the center’s persistence annoying, he said, but with the pandemic, schools started reaching out to ask if they could place students with the center, knowing that the staff had the capacity to keep students on track.

Like many of the masked students around him, 8-year-old Aydenn Aguirre was a regular at the Guadalupe Community Center long before the pandemic. He’s been part of their afterschool and summer programs since he was 5. He lists the ways the center has helped his family over the years.

“They buy us a lot of Christmas presents,” Aguirre said. “And a water bottle.”

Those details mean a lot to Aguirre, who said he prefers to do his schoolwork at the center, where it’s quiet and the Wi-Fi will support his Zoom calls for school.

At the center from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., kids have a school day routine, Garcia said. Parents, many of whom are looking for work or taking whatever working hours are available, are spared the added stress of planning their day around online learning. They are also spared the woes of the steep technology learning curve. Canvas, the system San Antonio Independent School District is using for remote learning, is the same one Garcia is using for his graduate program. It’s complex, he said, so much so that he and his classmates needed support when they started using it. “Canvas was not made for the general public.”

Some students are at the day school as part of a suite of services to their family. Others start off in the program, and slowly their families find out that there’s more help available to them.

Some parents, while dropping off kids, open up to the staff about other needs. Sometimes kids bring it up. If Catholic Charities doesn’t have an appropriate program, rather than simply turning them away, caseworkers like Martinez will help them find the right nonprofit, ministry or government office. That’s how they’ve built trust with families who come in jaded with the systems and programs that have failed them in the past, Garcia said. “For them a utopian situation is so far-fetched.”

“Utopian” might sound like a strange way to describe having familiar faces ready to help with food, education and utilities assistance, Garcia acknowledged. But for those living in poverty while the pandemic pulls them further and further from stability, it can be just as rare.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)