For the First Time, EPA Could Order Schools to Test Water for Lead, but Experts Warn That Doesn’t Mean It Will Be Safe to Drink — or That Lead Will Be Removed

As Newark, New Jersey, Flint, Michigan, and other cities continue to grapple with lead in their water supplies, the Environmental Protection Agency is mulling changes to the decades-old regulation meant to protect Americans from the highly damaging contaminant.

Among the proposed changes to the Lead and Copper Rule are a first-time national requirement to test water in schools and child care facilities for lead and an extension to the amount of time water companies have to replace lead pipes. Lead is a known toxin that can cause irreversible developmental and physical problems, especially in those who ingest it as children.

The changes are part of a wider effort by the Trump administration to reduce childhood lead exposure, but advocates say the proposal could actually weaken water protections while creating a false sense of security about how much lead is seeping into the system and whether it poses a danger. The agency is taking public comment on the proposal until Feb. 12.

“EPA actually committed back in 2005 that it needed to revise the Lead and Copper Rule because it was inadequate for dealing with these lead crises,” said Elin Betanzo, a water engineer who was instrumental in uncovering the Flint water contamination. “There are a few provisions in there that do improve [the rule] a little bit, but then there are other provisions that I see as really weakening overall our protections for lead in drinking water. So far, I don’t see the huge improvement in public health protection that I was hoping to see in a Lead and Copper Rule revision.”

At an elementary school in Clark County, Nevada, EPA officials on Oct. 10 announced the proposed changes to the regulations. EPA Pacific Southwest administrator Mike Stoker said Clark County is a “role model,” the Las Vegas Sun reported, because it has already been testing water for lead even though federal law does not currently require it. EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler also announced the proposal at an event in Green Bay, Wisconsin, around the same time.

While some states and localities like Clark County have already taken action on their own, Stoker touted the proposed change to the law that would mandate for the first time that the water in schools and child care facilities nationwide be tested for lead. The additional testing requirement is one potential change among many to a complicated regulation created in 1991 that falls under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

The revisions would require water utility companies to test 20 percent of the schools and child care facilities they serve every year, checking the water at all of them over a five-year period. The changes would mandate that water samples be taken and tested from five taps at each school and two at each child care facility.

Erik Olson, a senior strategic director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, a nonprofit focused on environmental issues, sees potential pitfalls. The new testing requirement could produce misleading results because lead levels in water can fluctuate depending on numerous factors, he said. The levels can also vary within a building, so samples from a handful of taps aren’t representative of the untested faucets.

“If you do more frequent monitoring, you’re going to find more problems because, by its nature, lead contamination varies from time to time and even with how the water’s turned on and off, how long the water sits, all those kinds of things, so we are concerned that people may say, ‘Oh, well, our water was tested in our school and there’s no problem,’ when all they did was test five taps once every five years and may overlook the problem,” Olson told The 74.

The testing requirements could also add new burdens to schools and states without adding much public health benefit, Betanzo, the water engineer, who also worked at the EPA from 2000 to 2008, told The 74. Most states are responsible for making sure water systems comply with the federal Lead and Copper Rule.

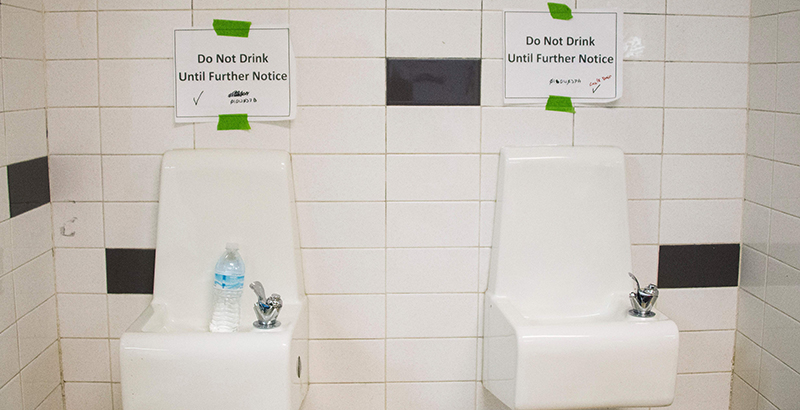

Despite requiring testing, the proposed revisions to the federal rule do not order states or schools to take action to remove lead if they find it in any amount.

Water systems, which are responsible for testing under the revisions, would be required to alert school officials, leaving the decision about whether to act in their hands. The EPA recommends that schools take the the “3Ts” approach — training, testing and taking action on lead — but that guidance is optional.

Betanzo said she is also worried that teachers and families could receive information without the appropriate context. The federal action level for lead — the level of lead at which a water system has to do something to reduce contamination in its water supply — is 15 parts per billion. That’s a measure of corrosion control for the water system, though, not an indication that water is safe to drink if lead is present at levels less than 15 parts per billion. The American Academy of Pediatrics and other experts say the only safe level of lead in water is none at all.

“I’m concerned that without very clear information about what to do with those sampling results, it will be very easy for schools and parents and families and staff to not understand the sampling data — to think that something that’s 15 parts per billion is OK for people to be drinking in schools, when it’s actually not,” Betanzo said. Moreover, even if schools or child care facilities are found to have more than 15 parts per billion of lead in the water, there’s no federal trigger for anyone to act to reduce or eliminate it.

The EPA’s stated goal with the revisions is to “reduce lead exposure in drinking water where it is needed the most,” according to an online fact sheet. An EPA spokesperson said in an email that the proposed rule changes take “a proactive and holistic approach to improving the current rule — from testing to treatment to telling the public about the levels and risks of lead in drinking water.”

Asked why the agency is not adding a mandate for schools to take action when lead is found in water at any level, a spokesperson said in an email that the EPA is authorized to regulate public water systems under the Safe Drinking Water Act and “recommends that the school or child care facility use the 3Ts guidance to help make decisions about communicating sampling results to the parents and occupants of the facility as well as any follow-up remedial actions.”

One advocate expressed concern but said the EPA is limited in what it can do to regulate what goes on inside schools and child care centers.

“What I sense from reading [the proposal] is a sincere desire to try to address the gap in the current Lead and Copper Rule regarding schools and child care facilities because lead exposure is so significant for children, especially in child care where the younger children are exposed,” said Tom Neltner, chemicals policy director at the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit working to protect the environment. “I think it was their attempt to try to fill that gap with the tools they had, but the law isn’t designed to really deal with this.”

There is no safe level of lead exposure for children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization. In addition to water, children can be exposed to lead through contaminated paint, dust and soil.

The consequences of lead exposure can be dire. In addition to lower IQ and behavioral problems, lead exposure has been linked to a higher likelihood of perpetrating violence as an adult. It can also cause anemia, hypertension, and problems with the kidneys, immune system and reproductive organs, according to the World Health Organization. Lead exposure for pregnant women can also cause miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight and premature birth, the WHO reports.

Since the water crisis began in Flint, the share of students needing special education services has nearly doubled there, The New York Times reported in November.

Replacing lead pipes could take more than 30 years

The proposed revisions weaken at least one key component of the current rule. The new rule would require water utility companies to replace at least 3 percent of lead pipes per year, effectively giving them 33 years to replace an entire lead-containing line. That’s a decrease from the current requirement to replace 7 percent per year, equivalent to about 14 years to replace a lead pipe.

Asked about this change, an EPA spokesperson said the existing 7 percent rate “is rarely occurring due to weaknesses in the current rule” and that the revisions, if enacted, would lead to more replacements “by closing these loopholes, propelling early action, and strengthening replacement requirements.” Advocates said that while the proposal does close some loopholes, they would like to see the agency go further in pressing for lead pipes to be removed from the ground.

The revisions include a “few modest tweaks in the rule that would be somewhat helpful, but I think overall the small tweaks … are swallowed up by this very problematic 20-year extension in how long it takes to pull the lead pipes out of the ground,” Olson of the Natural Resources Defense Council said.

There are some bright spots in the proposed revisions as well. For example, Neltner said, although the testing requirement could be better, putting schools and child care facilities in contact with their water utilities to identify problems is a positive step.

School chiefs call for complete removal of lead pipes

Lead-contaminated water was found in America’s two largest school systems, New York City and Los Angeles, in 2018, and since 2016, the metal has been found in school water in Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit and Portland, Oregon.

Although schools are unlikely to have lead pipes, the metal can get into water from fixtures and solder, even those that are billed as lead free. Until 2014, fixtures could contain up to 8 percent lead by weight and be labeled lead free; today the maximum is 0.25 percent lead for something to be classified as lead free, but even that is a high enough amount that it could leach into the water, experts say.

Child care facilities, which tend to be smaller, are more likely to have lead pipes, especially those based in private homes, said Lindsay McCormick, a program manager at the Environmental Defense Fund. This is a concern because children under age 6 are most vulnerable to lead, especially babies fed with formula using water containing lead.

A 2019 analysis of policies in 31 states and Washington, D.C., from Environment America, an environmental advocacy group, gave more than half of the states it studied a failing grade for protecting children from lead at school.

For schools, lead in water is one in a list of infrastructure challenges. The average school building in the United States is more than 40 years old, and in 2019 schools dealt with problems stemming from asbestos and lead paint as well as failing heat and air-conditioning systems.

Some states are taking initiative on their own. Michigan has a state Lead and Copper Rule, adopted in June 2018, that requires all pipes containing lead to be replaced by 2041, expands water testing and tightens other regulations. Lawmakers in the state have also introduced legislation that takes a “filter-first” approach, requiring schools and child care centers to provide filtered water for children and staff; a similar bill was introduced but died in committee in the Florida state Senate last year. Advocates tend to support the filter-first approach because it’s cheaper and more convenient than replacing pipes and fixtures, and it can be implemented sooner.

As of Feb. 3 — a little more than one week before the close of the comment period — 138 comments have been filed on the proposed revisions. Several commenters asked the EPA to extend the time allowed for input because of the complexity of the rule, which the agency did, adding 30 days to the original comment period. Some commenters urged the EPA to take a stronger stance on replacing lead service lines, while others seemed generally supportive of the changes, including many anonymous filers who said they thought the changes would strengthen public health protections.

At least six school district superintendents wrote letters to express concern about a potential lack of funding for schools and water systems to conduct the sampling and reduce lead if it is found. AASA, the professional organization for district superintendents, provided a sample letter for district leaders to use, and a spokesperson said the group planned to submit comments on behalf of several education organizations expressing worry that the proposal doesn’t go far enough to protect students from lead.

“It is time that the EPA acknowledges that we are past the point of addressing this problem through band-aid solutions in the form of new drinking water testing provisions, and instead, recognizes that our children are not safe without the complete removal of all lead service lines where kids live, learn, and play,” the letter says. The proposal makes some progress by adding testing in schools, AASA writes, but “still falls short of creating meaningful change.”

In fact, Betanzo, who founded and now runs her own consulting firm, Safe Water Engineering LLC, said the proposal could have a negative impact by diverting funds, which are already in short supply for schools, water systems and oversight agencies, to projects like school sampling that are limited in what they can accomplish.

“It won’t be a good scene,” said Betanzo. “It’s not going to be an improvement, and it’s going to take resources away from the important work that our water utilities and state oversight programs are already doing … I don’t see this being a positive moving us in the right direction.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)