Michigan, Flint Schools to Pay for ‘Unprecedented’ Lead Screening Program for Children Affected by Water Crisis

All children impacted by the Flint water crisis will be eligible for universal screening for educational and health problems associated with lead exposure, attorneys announced Monday.

“This is truly an historic partnership between the state, the county, Flint community schools, the Flint community itself, and the public health community. It is one that we believe is unprecedented and groundbreaking,” Greg Little, chief trial counsel at the Education Law Center, said on a call with reporters.

The Education Law Center and the ACLU of Michigan brought a class-action lawsuit on behalf of Flint children in 2016, alleging that the state of Michigan and Flint schools failed to appropriately identify children with special needs and provide them with appropriate services — a problem that is likely to worsen as additional children who may have been exposed to lead in the city’s water enroll in school.

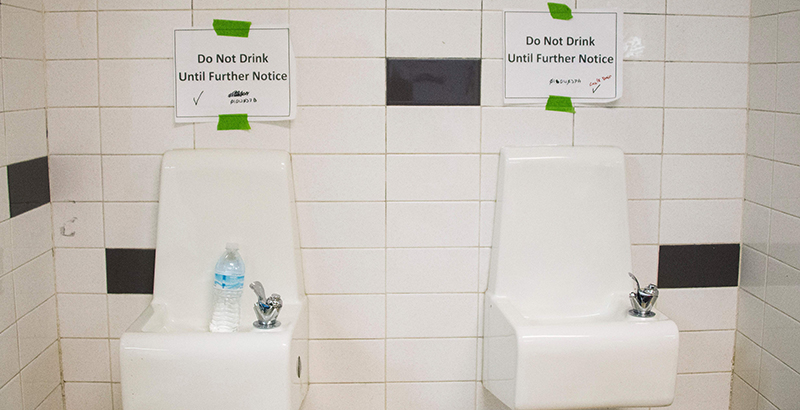

The partial settlement came just days after Michigan state officials announced they would no longer provide free bottled water to Flint residents. Gov. Rick Snyder in a statement that lead levels are below what the federal government considers dangerous, though many residents still don’t trust the water system, The Detroit News reported.

Impacted children will be eligible for screenings through the Flint Registry, a citywide public health tracking system for all Flint residents, adults and children, to identify potential health and education problems. The system goes online in September.

The settlement with the Michigan Department of Education, Flint Community Schools, and the Genesee Intermediate School District will allow all children, regardless of the results of an initial screening, to undergo additional neuropsychological exams, if requested by parents. Attorneys described the neuropsychological exams as the most advanced testing for the effects of lead exposure.

Results of the tests will be sent to schools as children are evaluated for special education services. The program will also fund training for teachers on identifying children potentially harmed by lead exposure.

Flint’s current lead exposure crisis dates to 2014, when state-appointed city managers switched to a less-expensive, contaminated water supply that wasn’t treated with the necessary chemicals to prevent lead from leaching from city pipes. Long-term effects of even minimal lead exposure on children can include learning disabilities, lowered IQ, and health problems.

Third-grade reading scores in Flint last year plummeted, though other factors besides lead exposure, including more rigorous standards, may have been among the causes.

Monday’s agreement is the first step in settling the 2016 class-action lawsuit.

Other allegations in the lawsuit concerning the availability of necessary services for students with disabilities, and the inappropriate use of discipline with special needs students, are still pending. Attorneys hope this settlement will spur the state and districts to settle the remaining issues, Little said, but if not, attorneys will continue the lawsuit.

“We will be there for these kids going forward, as long as necessary, to provide them the services they need,” he said.

The state will have to provide an initial $4.1 million to set up the screening program, with further funding coming from Medicaid and other funding sources, attorneys said. The settlement acknowledges that the funds “may be subject to legislative approval” and that the agreement will be null and void if lawmakers don’t approve the funding.

As many as 25,000 to 30,000 children may be eligible for screening, Little said.

Though the Flint Community Schools only enroll about 4,500 children, the settlement will cover those attending charter schools, children who are too young to enroll in school, young adults up to age 26, and children who may have only been in Flint for a brief time — for example, those visiting family, attorneys explained.

Enrollment in the registry and participation in screenings is voluntary. The partial settlement agreement goes before a federal court for final approval on April 12.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)