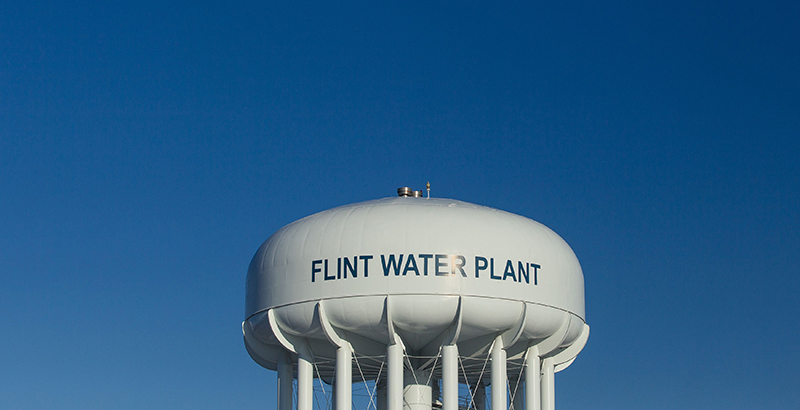

A Student’s View: Flint’s Poisoned Water and Finding Structural Racism ‘in the Fine Print’

Twenty-four students from Lowell High School in Massachusetts set out in 2016 to understand the meaning of diversity and equity in America. As part of a course titled “Seminar on American Diversity” created by history teacher Jessica Lander, the students wrote Defining Diversity, a book of essays charting a concise journey through a century and a half of seminal moments in American history. The students’ hope is to help peers across the country understand key ideas, federal laws, constitutional amendments, and Supreme Court decisions that have shaped our society.

Defining Diversity has special resonance — Lowell High was the first integrated high school in the U.S. — open to all from its founding in the 1830s. Today, it is one of the most diverse schools in the nation, with students from 66 countries across five continents and a study body that is 32 percent Asian, 30 percent white, 23.8 percent Hispanic and 11.3 percent African American.

Defining Diversity, published in May 2017, has been shared with schools in nearly all 50 states. The book is composed of 30 essays. Below is one of them, written by then-senior Onotse Omoyeni. Omoyeni is now a freshman at Howard University studying English, political science, and Arabic. She hopes to pursue a career in politics and law.

Learn more about Defining Diversity or purchase a copy here. Meanwhile, Lander’s students in the current “Seminar on American Diversity” are working on writing a new book, this one profiling U.S. activists and changemakers, both young and old, who have spoken out on issues of equity and justice.

In Flint, Michigan, 60 percent of people are black and 4 of every 10 people live in poverty. Flint has little funding supporting its community; thus, those with the greatest need are deprived of resources. Instead of using state resources to address the challenges facing Flint, the state of Michigan decided not to invest in its citizens, pulling resources and severely cutting the budget.

In April 2014, city officials attempted to save money by switching the water supply to a regional water system that wasn’t ready for use yet. While the city waited, they used water from the Flint River. Soon, citizens began to complain about the taste and color of tap water. The city tested the water and found the bacteria E. coli.

To get rid of the E. coli, the city pumped chlorine into the water supply, which damaged the pipes, allowing lead to seep into the water. The city’s water became astonishingly polluted, with lead levels 1,000 times higher than what would ordinarily trigger federal intervention. The pollution caused some residents to break out in rashes, others to have their hair fall out, and others to suffer impaired cognitive development and mood disorders.

It’s difficult to imagine a similar crisis happening in a wealthier, whiter city. What happened in Flint is the product of structural racism — something subtler than what you may have studied in school. Its existence is based on a long history of racial hierarchies that manifested in laws and policies that give advantages to white people, while producing negative outcomes for people of color. Structural racism is racism perpetuated by the fine print.

So what happened in Flint? Throughout the 1960s, the Federal Housing Administration had explicit instructions to deny or limit financial services in Michigan and elsewhere “based on racial or ethnic composition.” This practice, known as “redlining,” made it easier for white people to receive better housing. This encouraged self-segregation, as white people living near people of color were able to move to better neighborhoods.

Redlining was combined with state and private discrimination actions to prevent people of color from achieving economic stability. Preventing people from fully participating in the economy meant that even after the destruction of explicitly racist policies, people of color no longer had economic power. Cities like Flint became majority black and increasingly poor as wealthier white residents left for the suburbs.

Structural inequality is not limited to Flint but is unfortunately embedded in many communities across the country. It is imperative that all of us in America understand and confront structural racism. Outside of our moral and humanitarian obligations, the poisoning of Flint’s water clearly illustrates how political and economic racism can have dire effects for vulnerable populations.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)