English Learners Make Significant Gains in Reading Despite Pandemic Disruptions

Positive outcomes — particularly in Chicago, L.A., Albuquerque and Fort Worth — come amid horrendous mathematics scores for most

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

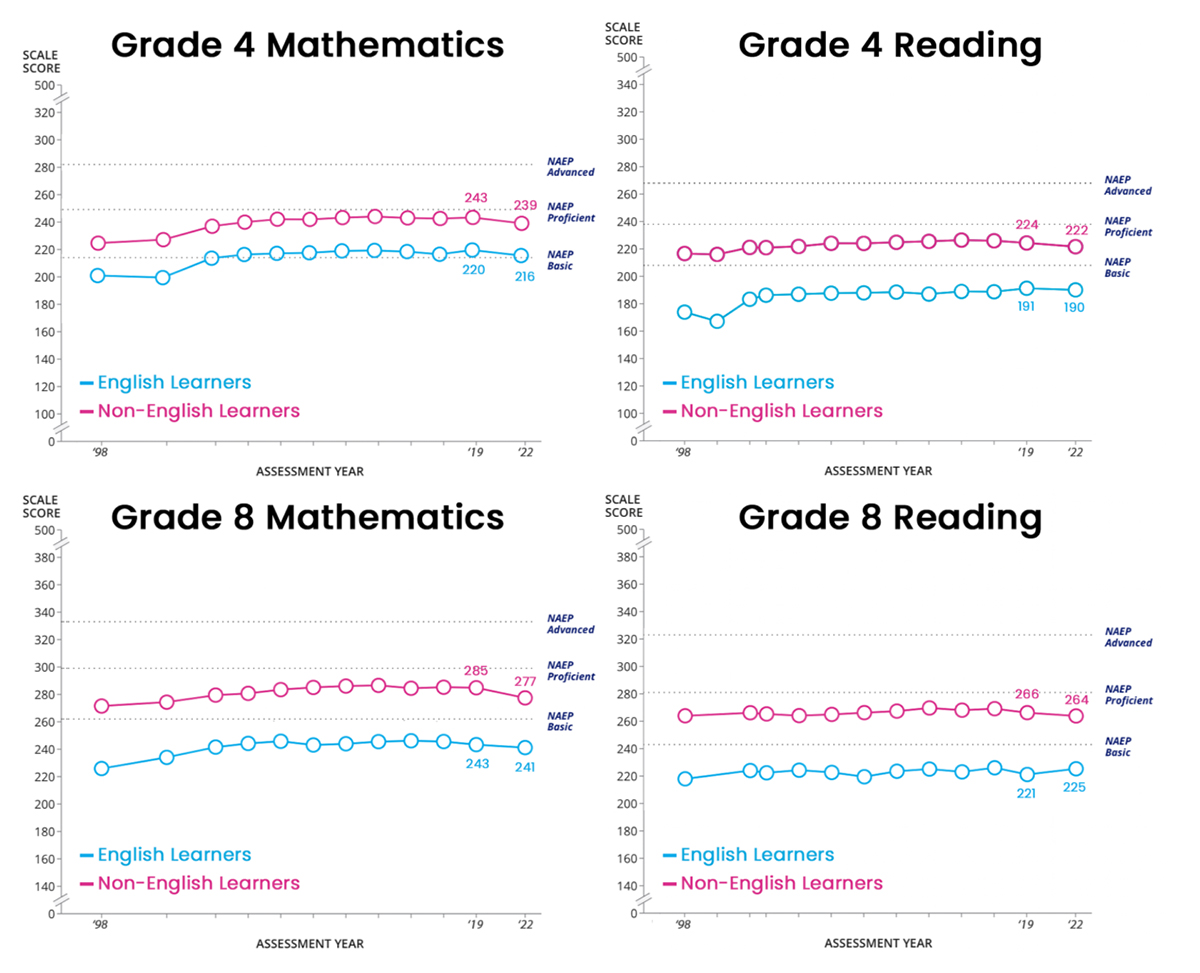

While abysmal math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress exams have parents and educators worried about students’ futures, English learners made a surprising gain, scoring four points higher in 8th-grade reading while student results overall dropped.

The upward trend was even more pronounced in several major cities whose NAEP results are tracked separately. In Chicago, now home to the country’s fourth-largest district, the score for English learners on the eighth-grade reading test shot up a jaw-dropping 17 points to 234, the highest level since reading data was first reported on this group in 2002 and 10 points more than the next-highest score of 224 in 2017.

The same held true in Los Angeles, the district with the most English language learners in the country, where their eighth-grade reading scores leapt from 202 to 210. That eight-point gain essentially mirrors a much-discussed nine-point gain all L.A. 8th graders made in reading on the 2022 exam.

The 8th-grade reading scores for English learners in Albuquerque climbed from 211 to 223. Fort Worth, Texas also showed remarkable gains, with scores jumping from 219 to 231. Nationally, English learners’ scores on the eighth-grade reading test went from 221 to 225.

The scores for English learners are still far below NAEP’s grade-level proficiency for math and reading and sizably lower than the scores for students overall, but remain noteworthy in a closely watched test where changes of even a few points are considered significant. They also are emerging after a pandemic that harmed all student learning, but was seen as particularly detrimental to English language learners.

While some educators, including Los Angeles Unified schools chief Alberto Carvalho, point to concentrated remediation — the superintendent cited tutoring and summer programs targeting these children — others are less sure why these gains were made.

“I don’t know that I have a good explanation for why that would be,” said Tim Boals, founder and director of WIDA, an organization that provides resources to those who teach multilingual learners. “I’d like to think that maybe we’ve been doing a better job of supporting ELs over the last few years, but I don’t have evidence to support that conclusion. It also flies in the face of the COVID panic about our kids losing even more ground.”

Grady Wilburn, a statistician and research scientist for the National Center for Education Statistics which administers NAEP, also could not explain these students’ success, especially considering the obstacles they faced throughout the pandemic.

Multilingual learners were, in some cases, more transient because of their parents’ job loss and unstable housing, and, as a result, often more difficult to find. They were also less likely to have reliable internet access and devices through which to learn remotely.

“Anything we saw that showed improvement we saw as a surprise,” Wilburn said. “We don’t have a good explanation as to why.”

Carol Salva, a Houston-based educational consultant who has worked with multilingual learners for 15 years and is recognized as a leader in the field, is unsure what to make of the results. While she hopes they reflect a substantive improvement — she observed that multilingual learners benefited from having additional time to complete assignments and were more likely to talk during online lessons when they could type rather than speak their comments — she’s concerned about their meaning.

“While I’m grateful for any positive news when it comes to our multilingual students, this data gives me pause and I feel that it needs to be studied further,” she said.

Chicago focuses on its English learners

Jorge Macias, chief of language and cultural education at Chicago Public Schools, said the improvement among English learners in his district was no shock: CPS, which currently serves 73,000 such children, has been focusing on this group for years, increasing the number of bilingual and English-as-a-second-language teachers from under 5,000 in 2014 to well more than 6,000 now.

The 325,000-student district also has invested in rigorous training for staff who then share their knowledge with teachers at hundreds of schools. Their tactics are constantly evaluated for their effectiveness and measured against student achievement, Macias said.

The University of Chicago, in a study published in 2019, found that CPS students who started out as English learners and who demonstrated English proficiency by eighth grade had higher attendance, math test scores, and core course grades than their peers. So, even a force as strong as the pandemic couldn’t derail them, Macias said.

“We had a four- or five-year runway of getting all of these structures in place to achieve that outcome,” he said.

Los Angeles in the NAEP spotlight

Carvalho, the longtime Miami-Dade superintendent who took over in L.A. March 1, also cited an easier transition to online learning than some other major cities, although there have been multiple reports of L.A. Unified students struggling with remote instruction. And while Los Angeles was among the last in the country to return to in-person schooling, the district saw improvements for all of its students in 4th-grade reading and in both 8th-grade reading and math.

Carvalho has been on the receiving end of both praise and skepticism since the NAEP scores were released last week, especially because his students lost ground in both math and reading on the 2021-22 California state tests. The veteran superintendent noted that NAEP advises school leaders “to be careful about drawing conclusions based on NAEP data.”

Longtime education researcher Tom Loveless put an even finer point on it, telling The 74, “tests are fluky, and they go up and down. L.A. may give up all those points in the next administration of the test. A lot of people who cheer the NAEP one year are downtrodden the next.”

English learners narrow the gap

Jennifer Lumb, who teaches multilingual learners at Oakbrook middle and elementary schools in Ladson, South Carolina, said her students’ attendance was solid throughout the pandemic for classes involving English language instruction.

“The majority of my students missed the in-person peer/teacher interactions, so they looked forward to that connection with our daily virtual (English language) instruction,” she said.

But they didn’t always log-on for their core subject matter courses, she said.

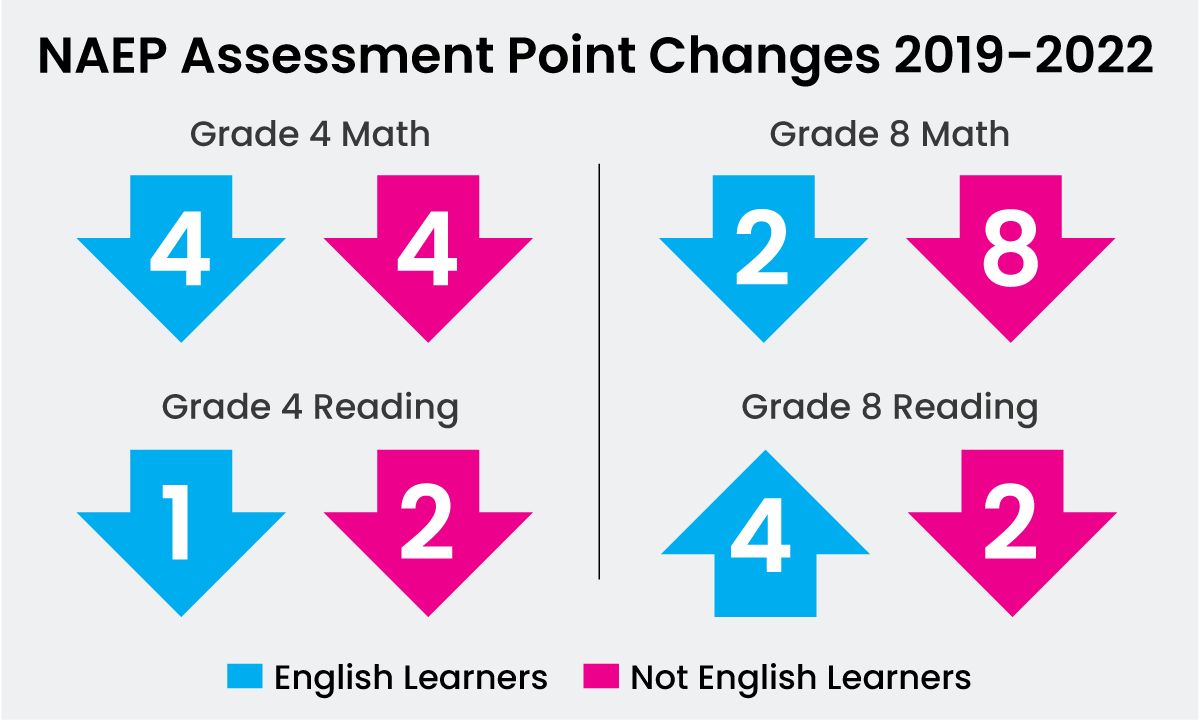

Nationally, scores dropped in eighth-grade math across the board, but less so for English learners. They slipped just two points — from 243 in 2019 to 241 in 2022 — while they nosedived from 285 to 277 for all non-English learners in that grade and subject.

Fourth-grade reading scores also decreased, but the shift was closer between the two groups and not as stark. They went from 224 in 2019 to 222 in 2022 for those students who were not identified as English learners — and from 191 to 190 for those who were.

In fourth-grade math, both groups saw their scores sink by four points — from 220 in 2019 to 2016 in 2022 for English language learners and from 243 to 239 for those students who were not.

But the gap between English learners and all other students — long thought to have widened during the pandemic — didn’t grow: It stayed the same for fourth-grade math, decreased a point for fourth-grade reading and decreased by six points each for eighth-grade math and reading.

And not all cities reported gains: Eighth-grade English learners’ reading scores held steady in Washington, D.C., at 224, and fell by a point in New York City to 208. Miami also suffered a loss, with scores dipping from 225 to 222. Boston dropped four points to 2016.

More than 115,000 students took the eighth-grade reading test in 2022, down from roughly 146,000 in 2019, Wilburn said. The percentage of English learners who took the NAEP tests remained almost unchanged between 2019 and 2022. In 2019, 13% of all students who took the 4th-grade math test were identified as English learners, in 2022, 14% were. In 4th-grade reading, 13% of all students who took the 2019 test were English learners as were 15% of students who took the 2022 test.

No matter the scores, Boals said, educators must advance these children.

“At the end of the day, the issue is supporting the kid who’s in front of you and moving him/her forward,” he said. “That, for me, is always the main thing.”

The 74’s senior writer Kevin Mahnken contributed to this report.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)