74 Interview: Shep Melnick on Brown at 70 and Integration’s Failure in the North

Undefined goals and lack of guidance from Washington stalled the movement’s progress, the political scientist writes in his latest book.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For 70 years, the U.S. government has worked to desegregate K–12 education, with Congress, federal courts, and cabinet agencies prodding state and local authorities to assemble more racially diverse schools. That national mission, begun in 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education, encompasses decades of litigation and untold changes to the structure of schools and districts, all in the name of more equal access to educational opportunity.

Whether the endeavor has been successful is a debatable proposition, and one that never strays far from the headlines. After years of using affirmative action to accept more African American and Hispanic applicants, elite universities like Harvard were prohibited by the Supreme Court last year from adopting racial preferences in admissions. And diversity programs at the K–12 level have come under greater scrutiny as well, with plaintiffs around the country weighing lawsuits against equity-minded admissions policies at selective high schools.

In his latest book, political scientist R. Shep Melnick investigates the course that desegregation followed over three generations — and where it fell short.

The Crucible of Desegregation, published by the University of Chicago Press, follows the legal maneuverings and unintended political consequences of one of America’s foremost social justice movements. Situating its subject within the larger struggle to extend democratic citizenship to women, minorities, immigrants, and people with disabilities, the book mainly focuses on the era between the exuberant 1960s and the anxious 2000s, when the victories of the Brown coalition seemed to be fading.

In his work as a professor and researcher at Boston College, as well as the co-chair of the Harvard Program on Constitutional Government, Melnick has studied the development of what he calls the “civil rights state” as it developed over the 20th century: a colossal edifice of statute, caselaw, and regulatory language that America has built to shape its maturation into a more perfect union. His prior writings on the ever-evolving nature of Title IX have identified the junctures when judges and agency staffers, operating between the lines of federal laws, gradually pushed educational institutions in radically new directions.

Melnick’s treatise on desegregation adopts a similar posture toward federal courts and the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (the precursor to the Department of Education). He argues that unelected civil servants, operating with insufficient guidance from the Supreme Court or Congress, embraced a spate of injunctions and racial balance plans — some still in effect more than a half-century later — that helped shatter the archaic social order of Jim Crow. But when the sweep of legal action turned northward, he argues, the political wars around busing in urban school systems halted much of the progress that racial justice advocates hoped to achieve.

In a wide-ranging discussion with The 74’s Kevin Mahnken, Melnick spoke about the never-ending demographic shifts in American schools, the birth of education reform as a successor to the desegregation movement, and what he deems the poor-quality social science that influenced the courts of Earl Warren and Warren Burger.

“If we could have schools with a good mixture of kids from all racial backgrounds, that would be terrific,” Melnick said. “But what’s the cost? How many hours on the bus? How much isolation of parents from schools? Are the backgrounds of the poor and affluent kids so divergent that they develop stereotypes or animosity?”

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Do you see desegregation as a failure?

No. I’d say that desegregation in the South was a tremendous success, and we have long-term evidence of that. It broke down the racial caste system, it was essential, and we should give a lot of credit to the courts and Congress for passing the Civil Rights Act.

In the North, it was a failure. The situation was different, and the school districts were different. We took the model that applied to breaking down a racial caste system and put it in effect where it did not apply. The long-term consequences there would seem to be null.

As a federal priority, desegregation also had ripple effects on school finance and other disadvantaged groups — such as English learners and students with disabilities — that were often quite good. But race is always the hardest nut to crack.

Can you take me through the earliest stages of desegregation, after the Brown decision in 1954? The historical consensus is that, largely due to resistance from local officials in the South and elsewhere, not a lot of actual integration took place through that initial period.

That’s generally true, but with one important caveat. In the border states, and in some states in the North where segregation was not strongly entrenched, there was very rapid desegregation. I’m talking about places like Kansas, where the Brown case came from, Kentucky, and Tennessee. An interesting one is Delaware, where there had been significant segregation, but they were able to quickly desegregate.

So there was significant change in those border states, in part because school segregation was not part of a broader system of racial segregation to the extent that it was in the Deep South. There also weren’t so many African American students, so the change didn’t seem so great. This shouldn’t be overlooked.

One of the key ideas you explain is the distinction between “colorblind” integration — the early idea that courts could simply strike down segregation laws and let schools do the rest — and the more assertive mandates that followed, which required authorities to actually achieve a specific balance of racial representation in classrooms. When the first, more incremental approach gave way to the second, was it essentially out of frustration that more hadn’t been accomplished by the mid-1960s?

Yes. The use of numerical standards for racial balance grew out of frustration with Southern school officials, who, often aided by judges on Southern district courts, used every trick in the book to avoid desegregating. The claim was, “We’re not using racial classifications, it just turned out that nothing changed!”

It led to a sense among the courts, as well as the Office of Civil Rights — in what was then the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare — that we needed some standard to determine whether states were making good-faith efforts. That was the beginning of using statistics of racial balance to get some action, and while it was greatly overdone later on, my view is that it was entirely reasonable and necessary at that stage.

They were simply saying, “You’ve got to show that you have at least 20 percent of African American students going to school with white students.” We needed some standard, and that was the turning point.

Was the critical threshold the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act? That law included Title VI, which allows the government to cut off federal funding to any institution that discriminates on the basis of race or sex. My sense is that power wasn’t frequently used, but it was at least a credible threat against districts that didn’t move toward more racial proportionality.

The threshold was a combination of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965. [ESEA] provided the carrot, in the form of more federal funds. Prior to that, there really wasn’t much to cut off.

We think of Title VI and the threat of federal funds being withheld as the chief enforcement mechanism, but I don’t think that was actually true. The chief enforcement mechanism turned out to be the use of the judicial injunction — desegregation orders. What Title VI and ESEA did was create a civil rights office, which eventually became OCR, that had regulation writing authority. It was those rules they promulgated that were then endorsed by courts, and the courts used their own enforcement powers to follow through.

There were essentially two choices: Comply now, desegregate, and get federal money; or stall, don’t get the money, and be subject to a judicial order later on.

You’ve written about the interplay between federal agencies and the courts, and how they can create a kind of ad hoc civil rights regime between their rulings and regulations. Did this dynamic play out with respect to desegregation?

That’s right. I’ve called it “leap-frogging” in the context of Title IX, and the same thing happened in the early days of desegregation.

The big difference between those two situations was that in the 1970s, both the Nixon administration and Congress told the Office of Civil Rights to stay out of busing. After that, their role became much less significant, and the courts were mostly on their own. But that relationship between the courts and agencies was crucial in the prior years.

Would it even have been possible to crack the resistance of Southern schools without resorting to desegregation orders and enforced racial balancing?

I don’t think so. While I have some sympathy for the colorblind argument in general, if we’d never gone to some kind of numerical standards, nothing would have ultimately changed. It was absolutely essential.

In hindsight, would it have been possible to undertake desegregation differently in various settings — for instance, through racial balancing in the South, but with a more limited intervention in the North, where school assignment patterns were more the result of de facto neighborhood segregation? Of course, there were recalcitrant segregationists in the North — the Boston School Committee of the 1960s comes to mind — but busing also met with so much animosity there.

There were opportunities for a different approach. The courts could have said, “If we find some evidence of discriminatory activity in the North, it doesn’t mean the whole panoply of federal interventions will apply.” Instead, they quietly eroded the distinction between de facto and de jure segregation, though they weren’t willing to say outright that they were abandoning it.

There was also a lost opportunity in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Fifth Circuit was debating about the extent to which you had to eliminate all predominantly Black schools. One of the judges, Griffin Bell — who later became attorney general under President Carter — basically said, “We should do what we can to increase the number of Black students who go to school with white kids. But when you have severe racial segregation in housing, we’re not required to eliminate all predominantly Black schools. For practicality’s sake, we need to have limits.”

He lost that argument, and it was the beginning of widespread busing. But I think it could have very easily gone the other way.

What about the legal rationale behind racial balance mandates, which has been criticized as condescending? Near the end of the book, you find statements from both Clarence Thomas and the critical theorist Derrick Bell — ideological opposites, or close to it — harshly critiquing the idea that African American students need to attend school with whites in order to learn.

If we could have schools with a good mixture of kids from all racial backgrounds, that would be terrific. My granddaughter goes to school in Berkley, California, and they seem to have accomplished that. I think it’s great, but what’s the cost? How many hours on the bus? How much isolation of parents from schools? Are the backgrounds of the poor and affluent kids so divergent that they develop stereotypes or animosity? All kinds of factors come into play.

One of the things that really bothered me while researching this project was the misuse of social science. There was this grand claim repeated over and over again in district courts, that if we had a 70-30 ratio of white and Black students, it would improve everyone’s education. That was based on incredibly poor research. The courts were sold a bill of goods — the argument that, if we had whites and Blacks together, racial harmony would prevail. We know that wasn’t the case in some circumstances.

The problem was that we started by using racial balance to overcome years of de jure segregation and massive resistance, but then we claimed that it was an educational benefit on the basis of shoddy evidence. Going back to the Brown case, it surprised me to learn how much even the NAACP legal team thought it was shoddy and that they shouldn’t cite it.

One of the themes the book keeps returning to is the difficulty of pursuing desegregation in a country where both legal and educational authorities are so decentralized. Can you break that down for me?

The way in which kids are assigned to schools, where schools are located, all of that stuff is done at the local level. Even states have basically no control over it, so all the key decisions were local decisions. In the middle of the 20th century, even funding was mostly local because it was based so much on property taxes.

This was one of the main political reasons for integrating: If kids of different races are kept apart, the white kids can be favored for funding, but if they’re together, you’ll get fairer funding. Fortunately, funding has become much more equitable over time. As a matter of fact, the Urban Institute came out with a study showing that predominantly black schools actually receive a little more funding per-capita than predominantly white schools.

With respect to courts, I’m hoping the book makes it clear that it’s a misunderstanding to think that the Supreme Court controls the federal court system. They don’t. They decide so few cases that district courts have huge power, especially over the nature of these structural injunctions that last decades. The Supreme Court basically said, “We don’t know what’s going there, and we’re not going to try to control it.” One of the things I discovered while working on this book was that decentralization is especially important in the enforcement of process.

The Supreme Court, under Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren Burger, obviously decided major desegregation cases through the 1970s. But as you say, they mostly seem to have left the lower courts to appoint special masters and issue desegregation orders — some of which remain in effect more than 50 years later — without a lot of guidance from Washington. And it’s not as though Congress filled the gap either.

Congress didn’t give any guidance because it was so badly divided on this issue. Various presidents didn’t want to give any guidance because they realized that, whatever they did, they’d get criticized for it.

The Supreme Court should have done more, but I think you’re right that Warren didn’t want to take ownership of this. After I finished the book, I found a quotation from former Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson. After the Brown case in 1954, he said, “I predict a generation of litigation if we send this ruling back with no standards, and each case has to come here to determine it standard-by-standard.” So some of the justices foresaw what was going to happen.

I think Warren’s hope was to write an opinion in Brown that would unite people, and I don’t blame him too much for that. What I do blame the Court for is not being more clear in the 15 years after that case, and then for meandering all over the place in the ten years after that.

The generational bookend to Brown is probably the Milliken v. Bradley ruling in 1974. The Court rules that segregation across city lines is permissible in the absence of discriminatory intent, and that largely white suburbs couldn’t be compelled to participate in Detroit’s busing initiative. My sense was that Milliken was responsible for dramatically limiting the scope of desegregation efforts, but the book seems to argue that the politics of busing was becoming untenable either way.

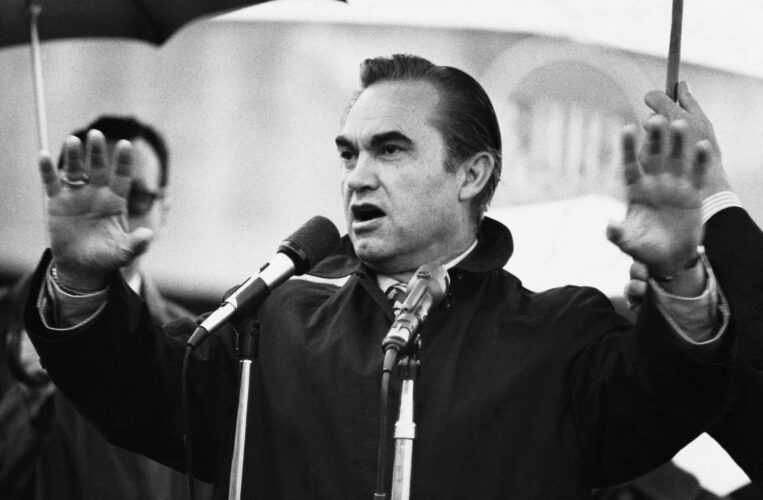

The reaction against what was going on in Detroit was so severe that George Wallace won the Michigan presidential primary in 1972. That says a lot — Michigan was the home of the United Auto Workers. Even its Republicans were liberal Republicans. At the same time, efforts to pass state constitutional amendments banning busing were gaining steam, and I believe they would have eventually passed if not for the Court’s ruling in Milliken.

In other words, busing was so politically toxic that I think it would not have survived. That would have been a good time for the Court to reevaluate the standards of constitutionality for desegregation programs, but they didn’t. To some extent, they seemed to pull back a bit, but then expand more after that. It really shows what happens when you have close, shifting majorities on the Supreme Court.

Can you describe the afterlife of that generation of jurisprudence on desegregation between the 1950s and the 1970s? You write a lot about the hundreds of desegregation orders in place around the U.S., some of which really evolved over the decades.

It really took the beginning of the 21st century for most of those injunctions to get unwound. We’re down quite a bit over the last 20 years or so, though some of them still exist. One of the things I discovered while researching the book, much to my surprise, was that no one had a very good idea how many there were because it was so decentralized. Schools often didn’t know whether they were under a court order or not, and the courts sometimes didn’t know whether that order was still in effect. Here’s a great example of the extent of the decentralization: ProPublica did a study of the remaining injunctions, as did the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and Brown University, and they all came out with different numbers!

Part of the reason for the uncertain state we’re in now is the 2007 Parents Involved case, in which the Court really clamped down on the use of racial assignments in K–12 schools. But Justice Anthony Kennedy was the deciding vote, and he wrote his typically amorphous, “on the one hand, on the other hand” stuff, so there seemed to still be room for some racial assignment in public schooling.One of the consequences of the recent Harvard case [ending racial preferences in college admissions] is that that’s no longer true, and racial assignments are going to be disallowed no matter what form they take.

That means that it’s just going to take more creativity for school districts to do what they want to do, which is achieve better racial balance. It will affect efforts to have more racial variety in exam schools, for instance. When you’re trying to reduce the number of Asian students at exam schools like Thomas Jefferson High School in Virginia, is that an example of racial discrimination? Those are the next big issues.

Would it be accurate to say that the education reform era was itself an heir to a desegregation movement that eventually had to transform? After the political and legal snares of the ’70s, you start to see more focus from both courts and legislatures on things like equalizing funding between schools, lifting state learning standards, implementing standardized testing, and so on.

You’re exactly right. Education reform grew out of frustration with the failure of previous efforts to provide better education to minority students, English learners and students with disabilities. We’d made progress with some of those, but it seemed to stall, and as the Nation at Risk report pointed out, even average students were starting to fall behind by international standards.

In all the reforms from the presidency of George H.W. Bush through George W. Bush and

No Child Left Behind, the plight of minority students was clearly central. And one of the most beneficial things that came from that period was testing, which allowed us to see how various schools were doing. I often tell my students that when the Every Student Succeeds Act was being negotiated in 2015, civil rights organizations insisted that there be very careful testing — and reporting of testing results — for minority students, because that’s the only way to tell which schools are doing well.

We’ve gotten much better at making school finance equitable. We’ve experimented with things like smaller classes and school choice, some of which seem to work and some of which don’t. But behind all of it is the idea that we have to improve opportunities for minority kids.

Here’s something you wrote near the end of the book: “It is understandable that half a century ago, federal judges and administrators believed they could use federal mandates to remake public education. With the benefit of decades of hindsight, we are no longer justified in taking such a leap of faith.”

Do you think the long story of federal involvement in K–12 education, typified first by Brown and more recently by NCLB, is coming to a close? Could it?

I think there are two possibilities.

One is that we will move back across the board. If Republicans win the presidency and both houses of Congress, I’m sure that’s going to happen. The other possibility, and what I’m hoping will be the case, is for there to be more experimental initiatives and more encouragement of states and localities to try new things. We should have more federal and state-level support for pre-K, which strikes me as extremely important. Kids enter the first grade with such divergent backgrounds that the most obvious place to begin is to make sure they don’t enter school way behind.

That’s a clear opportunity, and it’s pretty popular. Whether government will go in that direction or stick its head in the sand remains to be seen.

How do you think the desegregation period is remembered in our politics? The debate moment in 2019, in which Kamala Harris confronted Joe Biden about his opposition to busing in the 1970s, was so remarkable in that it felt like the party was totally revising its views of both the substance and the electoral risk of those policies.

Many of the talks I give on this subject are held in Boston, and what many people remember about busing is that it was a disaster in that city. But there are a lot of other school systems, especially in the Northeast and Midwest, where there is still a very bitter aftertaste from that experience.

At the same time, there’s clearly a sense among some people in journalism and the NAACP that desegregation was all working well until Milliken, when it was halted. Nikole Hannah-Jones has said something to the effect of, “It was working until racism stopped it.” That belief is relatively powerful on the Left because once you see everything in terms of racial identity, and once you see white supremacy as dominant, it’s a very easy story to tell.

We’re seeing what happens when these superficial understandings of oppressor vs. oppressed play out in politics, and it can be a very useful storyline.

Are schools re-segregating now? I’m aware that K–12 demographics have become much more diverse in recent decades, and it’s actually hard to answer that question.

The answer is that it depends on what you mean by “segregation,” since we’ve never really defined it. If you measure segregation as how many white students are in classrooms with Black students, that number of white students has gone down. So if that’s your sole measure of re-segregation, you can make that case, but it’s a very poor measure.

There are other measures: To what extent are Black students in classrooms with classmates of other races and ethnicities? That has been going up because there are more Hispanic and Asian students. To what extent have white students been going to school with non-white students? That’s been going up. If, by “segregation,” you mean white students isolated in all-white classes, that’s been going down.

The big factor here is that we have decreasing numbers of white students, who are no longer a majority, as well as increasing numbers of Hispanic and Asian students. This is particularly true in large cities. So almost all of this is demographics, and very little of it is policy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)