Biden-Harris Exchange Makes Busing a Surprise Focus of 2020 Campaign. How Will It Affect the Debate Over Integration?

So are the Democrats going to bus kids across town to integrate schools, or what?

That’s the question that has captivated the political media the past two weeks. While the Trump administration has careened from one news cycle to the next, absorbing damaging headlines on everything from its treatment of detained migrants to the president’s feud with the U.S. women’s soccer team, the Democratic side hasn’t budged from a sticky dispute over racial justice and public schools.

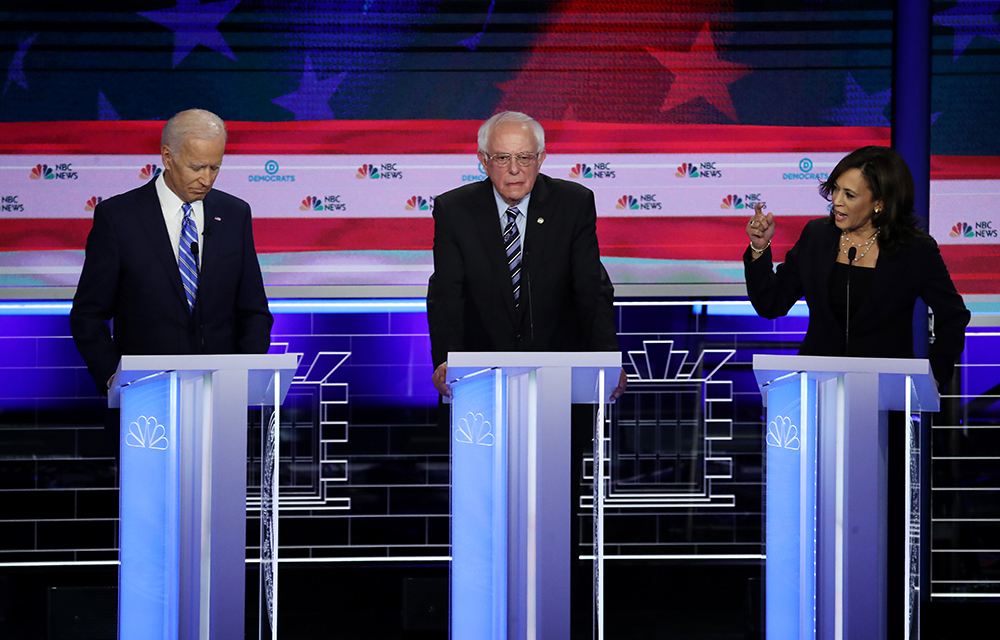

The fight was first triggered by former vice president Joe Biden’s remarks on segregationist politicians James Eastland and Herman Talmadge, which some construed as a misguided apologia for the Senate’s racist past. But it was kicked up a notch during the second debate of the Democratic presidential primary, when Biden was challenged by California Sen. Kamala Harris about his record on school busing in the 1970s. Biden’s response — that he had supported voluntary desegregation efforts by states and cities but not those mandated by the federal government — didn’t clarify whether he would act on racially segregated schools as president.

The exchange was by far the most memorable of the two-night debate, with pundits agreeing that Harris had scored a hit that could damage Biden’s standing with black voters. Polls have confirmed that Biden’s commanding lead in the primary has dropped several points in the period since, while Harris has enjoyed a meaningful surge in support.

But while the debate has lingered, it’s unclear whether the boundaries around the divisive issue of busing have truly been redrawn. Biden has offered an apology for his statements on Eastland and Talmadge, but Harris’s stated position on mandatory integration has softened in recent days, at times seeming to mirror Biden’s own. At the same time, several other Democratic candidates have offered their own plans to make American schools more diverse.

The somewhat halting intraparty conversation has commenced amid renewed interest in the idea of school integration, with journalists and academics drawing attention to the still-significant racial barriers surrounding many school districts. But even as Harris and Biden tangled on the controversy, they did so without taking it in new directions, instead manning battlements left over from political wars fought a half-century ago. And while Harris — herself bused to an integrated school as a child — succeeded in seizing the initiative, she appears unwilling to fully support a return to the days of compulsory busing.

Kfir Mordechay, a professor of education at Pepperdine University and a researcher at UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, said he welcomed the revival of busing as a live political priority after decades of neglect, but he wondered whether America’s political dialogue is equipped to accommodate such a charged topic in 2019.

“How do you judge someone and their opinions about an issue 40 years ago, and how do you have conversations about something that is a little bit more nuanced?” he asked. “It’s just really difficult to have that conversation, especially in the debate format we have right now.”

Busing remains unpopular

The re-emergence of school integration on a Democratic primary stage could be seen as surprising in some ways and utterly predictable in others.

In one sense, Biden’s front-runner status made it inevitable that he would eventually be attacked for his lengthy and convoluted history on the issue, whose salience has grown over the past few years. Education experts and activists have warned of a creeping “resegregation” of American classrooms triggered by the decline of court orders forcing school districts to bring together students of different ethnic backgrounds. By some measures, black and white students encounter one another less in school now than they did 40 years ago.

But a full reappraisal of busing would also be shocking purely on political grounds. Overwhelming political resistance to the practice — chiefly among white parents, but also coming from many minority homes — led to the outbreak of violence in putatively liberal cities like Boston, where terrified black children had to be protected from mobs as they made their way to school. Republicans Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were both able to mobilize the controversy on their way to landslide national victories.

In response, policymakers have spent decades devising ingenious systems to achieve more diverse schools with some measure of family consent, including the introduction of magnet schools and ranked-choice systems of school assignment that offer students a variety of options besides their neighborhood school. Many of the loudest voices in favor of integration, including the leaders of the left-leaning Century Foundation, cheer the emphasis of choice rather than top-down mandates. In several large cities, socioeconomic status is used as a proxy for race to gain even greater distance from the raw politics of the 1970s.

Halley Potter, a Century Foundation fellow who has written several reports on the success of latter-day integration efforts, argues forcefully that multiple methods exist to address the problem of segregated schools. She said the viral debate moment was “frustrating” because the controversy around busing has historically birthed arguments “specifically designed to undermine integration.” By focusing on the long commute times endured by students being transported to far-flung schools, she said, critics of the policy elided the social and economic conditions that made busing necessary in the first place: residential patterns that were meticulously segregated through years of discriminatory lending and zoning.

“It assumes that school integration means that students need to travel long distances,” she said. “That’s certainly not always the case, and there are many examples where schools become more integrated without increasing travel times for students much at all … If you’re talking about busing, that tends to assume that our school zones, to begin with, made some kind of sense that wasn’t racialized. And the truth is that in many cases, that wasn’t true.”

Another reason to skirt the issue of mandatory busing? It’s still not very popular. According to a 2017 poll from the education organization PDK, a sizable majority of parents value the principle of diversity in public schools. But both white and non-white parents said they’d prefer that their child attend a less diverse school that was closer to their home — by a 61-32 margin among whites, and a 52-40 margin among non-whites.

Pepperdine’s Mordechay said that the distinction between ’70s-style busing and integration plans of a more recent vintage “is hard to get across in these debates,” since so many parents see education as a zero-sum proposition: One child’s newfound opportunity could come at their own children’s expense. Still, underlining the agency of families is the method least likely to incur backlash, he said.

“You can have this system of controlled choice where, ideally, parents get to choose where they send their kids to school and get their top choice,” he said. “Of course, where you’re talking about neighborhoods that are segregated, that doesn’t always happen; but incorporating this choice element is a framework that is much more likely to be exported and accepted.”

‘Rarely a winning issue’

It’s not obvious where candidates like Biden and Warren will land on the dispute. After basking for several days in the success of her debate moment, Harris has proven somewhat evasive in characterizing her own stance on integration.

After stating that she forthrightly approved of school busing as a means of desegregating schools in 2019, she backtracked over the July 4 holiday, clarifying that the practice is merely “a tool in the toolbox” that districts could consider if they wished to achieve integration.

The apparent retreat caught the attention of both reporters and politicos, who openly wondered how that position differed from the one that Biden was criticized for offering during the debate. A Biden staffer later tweeted that Harris was “tying herself in knots trying not to answer” the question that she had posed to the vice president only days before.

It sounds here like @KamalaHarris is now taking something more like the @JoeBiden position on school busing. So what was that whole thing at the debate all about?https://t.co/bRDGzp7nvy

— David Axelrod (@davidaxelrod) July 4, 2019

Whatever the outcome of the dustup, integration advocates are generally pleased at the renewed relevance of integration in schools. Jason Sokol, a historian at the University of New Hampshire, said that he was encouraged by the debate and that while he didn’t think it necessary to “focus that much on the specifics of court-ordered busing,” Democrats should make the cause of disadvantaged children their own.

“It’s actually really significant for some leaders to be taking a stance on school integration,” he said. “I understand that it’s not all that politically wise to say that they want to bring back mandatory court-ordered busing. But if they want to think more creatively about ways to integrate our schools, then more power to them, and it’s really important for the leaders to be doing something like that. Because it’s rarely a winning issue politically to talk about ways that white parents in the public school system might send their kids to school with racial minorities.”

Sokol has written a lengthy account of then-Sen. Biden’s turn away from busing in the mid-1970s and how the anger of white parents helped stall further victories for the civil rights movement. When Biden took sides against federal efforts to achieve school integration through busing, calling it an “asinine” policy that deepened racial divisions, he opened the door for other liberal Democrats to retreat as well, Sokol found.

That could be seen as a significant loss, given the research and personal narratives pointing to the victories earned through a generation of intensive integration. One study of schools desegregated in Louisiana during the 1960s found that increased resources and more exposure to racially mixed classrooms led to a significant increase in the graduation rate for black students; additional research has suggested that the benefits of integration carried on well into adulthood.

“Everywhere that busing was tried, it had mixed results, but in some places, it really broke the back of the Jim Crow education system,” Sokol said. “But the media focused on places like Boston, which erupted in violence. And also, anti-busing leaders like Biden, who were playing to their angry white constituents, were successful in drawing this distinction between integration and busing, which was a false distinction.”

The Century Foundation’s Potter agrees that the past is a fair guide to future integration efforts, even while positing that “busing” is a limited — and limiting — lens through which to perceive the issue.

“It’s consistent to do both: I think we need to look back at the history, rethink why busing is always framed as a negative thing, and look at some of the real progress and the lives that were changed through those programs,” she said. “But if it’s possible, we should do that in a way that the conversation about school integration doesn’t stop there. That would be my way of having my cake and eating it too.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)