As Schools Brace for More English Learners, How Well Are They Being Served Now

Teacher staffing levels for English learners swing widely across the country and shortages abound, but appropriate class size can hinge on many things

Many schools across the country have seen their English learner population swell in recent years as immigration restrictions have eased and war, poverty and political instability continue to drive families from their homes.

Some campuses could see those numbers rise further still: In May, a COVID-era policy known as Title 42, which kept millions of people from seeking asylum in the United States, is set to expire — a development that comes amid a crippling teacher shortage in parts of the nation.

Newcomers’ impact on social services, including schools, has long been a talking point for conservative politicians. It’s also been posited as a fiscal crisis by New York City’s Democratic mayor, Eric Adams, who began busing new arrivals to Canada upon their request: His administration cited their rising numbers as a key factor in this month’s across-the-board budget cuts, including to the nation’s largest school district.

The White House has taken note of the educational imperative. President Joe Biden, in his March 9 budget address, proposed devoting $1.2 billion in fiscal year 2024 to help these students gain English proficiency — a $305 million increase over the current amount. He’s also pushing for an additional $90 million to build multilingual teacher pipelines through Grow-Your-Own initiatives and $10 million for post-secondary fellowships to further bolster the educator pool.

But it’s unclear if this new round of funding will meet the needs of one of the fastest-growing student groups in the country. English learners made up 10.4% of total U.S. enrollment in 2019, according to the most recent available federal data, up from 8% in 2000.

To gauge how these students are being served, The 74 reached out to 13 school districts across the country representing hundreds of thousands of English learners requesting information about their numbers and their teachers’.

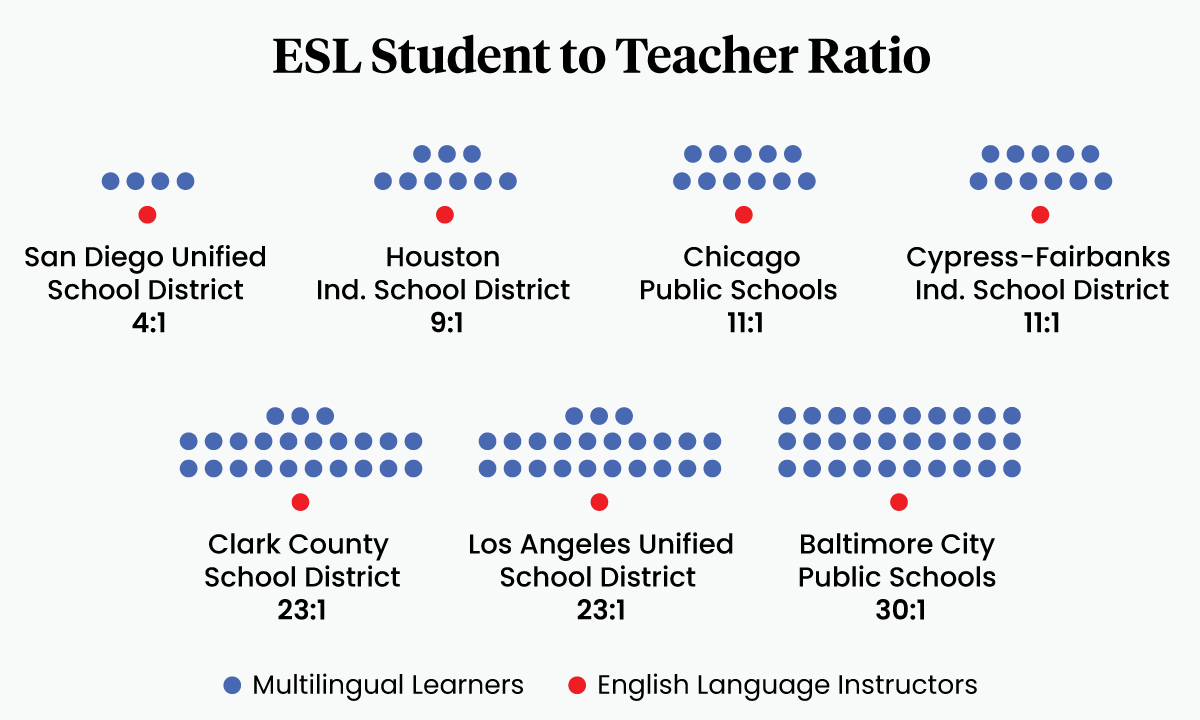

ESL Student to Teacher Ratio

Responses received over the past several months show dramatic differences in student-teacher ratios ranging from roughly 4:1 in San Diego, 9:1 in the Houston Independent School District and 11:1 in both Chicago and Cypress Fairbanks, which also serves Houston. It’s approximately 23:1 in Los Angeles and Las Vegas’s Clark County schools, and 30:1 in Baltimore City, though school officials there say it’s usually closer to 40:1.

“Most teachers are begging for there to be a cap on classes, but there usually isn’t,” said Pamela Broussard, a long-time educator who serves new arrivals just outside Houston. The magic number for her, she said, is 15, but the U.S. Department of Education does not regulate this figure, a spokesman said: It’s a state and local issue.

A manageable class size, experts and educators say, depends on students’ age, English proficiency, level of trauma and the instructional model used to help them, among other factors, including the teacher’s own training.

In the classroom

When queried about their experiences by The 74 on a Facebook group for English language instructors, dozens of educators replied, describing a vast array of conditions in the classroom.

Those with caseloads hovering around 20 or 30 generally found their workload manageable while those responsible for 75 or more multilingual learners found it untenable.

Some say they have supportive administrators, make great use of related technology, employ top-notch curriculum and work alongside highly trained peers in a single building — with the help of paraprofessionals.

Others say they are the only such teacher in their district, work across several campuses and struggle with scheduling, plus administrative duties and paperwork. Among the most exasperated are those who have little assistance and serve students of varying age, need and ability.

“No limit for me,” wrote one Oklahoma teacher. “I’m personally responsible for around 80 and do paperwork and supervise over an additional 30 to 40.”

Jody Nolf, a literacy engagement specialist based in Palm Beach County, Florida, said the appropriate class size depends on whether, for example, students missed years of schooling or were unable to read in their home language — all of which can slow their progress.

“Some teachers do well with 20 to 25,” said Nolf, who works with East Coast school districts. Others, she said, barely manage 10 to 15 when students’ needs are great.

“Few of us, however, teach in ideal circumstances,” she said.

If the primary purpose of English language instruction is for children to make gains in reading, writing, speaking and listening, Houston’s Broussard said, students need time to tackle all four tasks.

“Smaller class sizes give children time to talk,” said the teacher, whose charges, many of whom hail from Cuba and Venezuela, have lived in the United States for less than six months.

By the numbers

New York City Public Schools reported roughly 150,000 multilingual learners among some 919,000 students in the 2021-22 school year. The figure excludes charters — and the thousands of new arrivals who’ve enrolled in the past year.

Some 77,000 of these children were identified as newcomers, meaning they had three or fewer years of English language learner status. Roughly 9,500 of the city’s teachers had either a bilingual and/or English-as-a-Second-Language credential.

Teachers in bilingual education classes instruct students in two languages while ESL teachers focus on English — as do those labeled English to Speakers of Other Languages.

Georgia’s Cobb County serves more than 12,000 multilingual learners — more than 1,300 are newcomers — with 274 ESOL teachers. More than 1,800 other educators have some certification in this area, the district said, but it’s not clear how many teach English exclusively to these students.

Baltimore also serves a substantial number of newcomers, defined by that district as those who have been in U.S. schools for less than a year and are at the lowest English proficiency level. More than 1,500 of the district’s nearly 9,000 multilingual learners fit this category.

Brevard Public Schools in Florida has 723 such students out of 3,181 multilingual learners. It has 27 English to Speakers of Other Languages teachers to serve them. Seven positions remain vacant. The district also has 55 bilingual assistants — 16 spots remain open.

Students assigned to Clark County’s Global Community High School, designed to serve newcomers, enjoy a 10:1 student-teacher ratio: It has just 165 students and 16 teachers. Another 3,792 newcomers are elsewhere in the Las Vegas school district.

While many school systems across the country employ specially designated staff to help immigrant students build their initial inroads to learning, other districts, including Brevard, provide none. Houston ISD has 4,125 newcomer students and no specifically assigned staff to serve their unique needs.

Teacher training

As with class size, there’s little agreement regarding what constitutes teacher preparedness, a fact evidenced by vastly different state standards. Some educators who responded to The 74’s Facebook queries said they earned their credentials after passing a single test — many sought additional training afterward — while others had to complete numerous courses and spend many hours in the classroom working with multilingual learners.

No matter how they win the designation, said Diane Staehr Fenner, founder and president of SupportEd, which aims to provide educators with the skills and resources they need to serve these children, these instructors must understand how language works, use culturally relevant and responsive materials and have expertise in crafting and implementing effective lesson plans.

They must also collaborate effectively with other teachers, design appropriate classroom assessments and know how to interpret the scores their students earn on the state-wide English language proficiency exams that determine whether they are eligible for services.

Staehr Fenner credits the Teachers of English for Speakers of Other Languages International Association’s P-12 professional teaching standards for the criteria. She said these educators must also protect students’ legal rights; they should “really empower multilingual learners and all of the teachers who work with them.”

Schools are legally obligated to enroll all children who live within their district boundaries, regardless of immigration status, according to the 1982 Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe. Almost a decade earlier in 1974, the high court ruled in Lau v. Nichols that schools must provide appropriate services to students who do not yet speak English.

But multilingual learners face ongoing discrimination: Districts across the country have been sued for failing to admit and properly educate these children.

Boston Public Schools has been under court order since 1994 to direct a more equitable share of its federal funding toward this group, but last month a longtime legal monitor said Boston school leaders recently defied requests for the records documenting how it spent the money.

Learning a new language

The goal of providing appropriate services is to move newly arrived and non-English speaking students to the place where they are proficient and can learn in English without additional support.

Tim Boals, founder and director of WIDA at the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, said studies show it takes either four to seven or five to seven years for a child to exit ESL services. But there are variations: Some children graduate from such programs in three years, he said. For others, it takes longer.

“Being younger is assumed to be a big advantage, but that’s not always the case,” he said. “If kids don’t come with basic reading skills in their home language, that can slow things down. Arriving in high school can also be hard since kids have only four to five years typically to ‘catch up’ and accrue credits.”

Added time is unlikely in many classrooms as teacher shortages persist: While the English learner population is growing, staff are lagging.

Officials from Baltimore City Schools, who said they travel all over the country looking for staff and also recruit from overseas, hope to hire at least 25 more teachers in the coming months to serve this student group.

The need was so drastic last fall that administrators and other leadership staff went back into the classroom to teach, with some staying on for months.

“Every year has been hard trying to find teachers,” said Lara Ohanian, the district’s outgoing director of differentiated learning. “After the pandemic, with this national teacher shortage, we have seen even more challenges.”

Ohanian said the student teacher ratio varies throughout the year and is more typically 35 or 40:1.

It can be difficult for schools to plan or predict class size as many children arrive long after the academic year begins, said Ferlazzo, of Sacramento, a city that has become home to refugees from all over the world.

“Schools didn’t know a Russian invasion of Ukraine would cause an influx of refugees late in the school year,” he said. “Or know the Afghan government was going to collapse.”

Florida’s Duval County Public Schools has 9,597 multilingual learners and 2,747 teachers to support them: 329 held an English to Speakers of Other Languages K-12 certificate, which requires passing an ESOL K-12 Area test, and much of the remainder had an ESOL endorsement, which demands 300 hours of specialized courses.

The district had 3,199 newcomer students and 77 teachers to support them. The Los Angeles Unified School District, the nation’s second largest, has 6,786 in grades 9 through 12 alone — and 19 dedicated staffers at three high schools to help them.

The Paradise Valley School District, which serves students in the Phoenix area, has 2,024 multilingual learners this school year and 69 properly endorsed teachers who teach targeted English language development.

McAllen Independent School District, located on the Texas-Mexico border and long accustomed to serving newcomers, is home to 7,338 English learners and has more than 550 teachers to serve them.

A trio of reactions to new arrivals

The resources allotted to these students might depend on their reception by their school district: In some cases, Sacramento’s Ferlazzo said, immigrant students are considered an inconvenience.

“Their needs are not prioritized,” he said. “That might result in putting (English learners) into classes with English proficient students with no extra support at all.”

Ted Hamann, professor in the Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at the University of Nebraska Lincoln, has long studied children who were educated in both America and Mexico as their families traversed the border.

He said schools and communities faced with a significant uptick in new arrivals react in three ways: through a spirit of welcome, disquiet or xenophobia.

In the first instance, people regard the influx as a positive development, a reflection of their town’s attractiveness to newcomers. In the second case, locals note the change with curiosity or uncertainty, but general neutrality.

The last reaction is hostile, in which newcomers are cast as a threat or contaminant.

“What is striking,” Hamann said, “is that in most of the communities we work in, we see all three.”

On campus, it’s up to school leaders to determine which reaction is dominant, he said, adding our duty to educate multilingual learners in this country should hinge on a belief that all children deserve investment, no matter where they come from — or where they are headed.

“We owe in the present to these kids a future that may or may not be geographically local,” Hamann said. “What kind of world do we want to live in — where we have reciprocity to each other, or we don’t? Can we be generous to each other or is it this desperate struggle for survival?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)