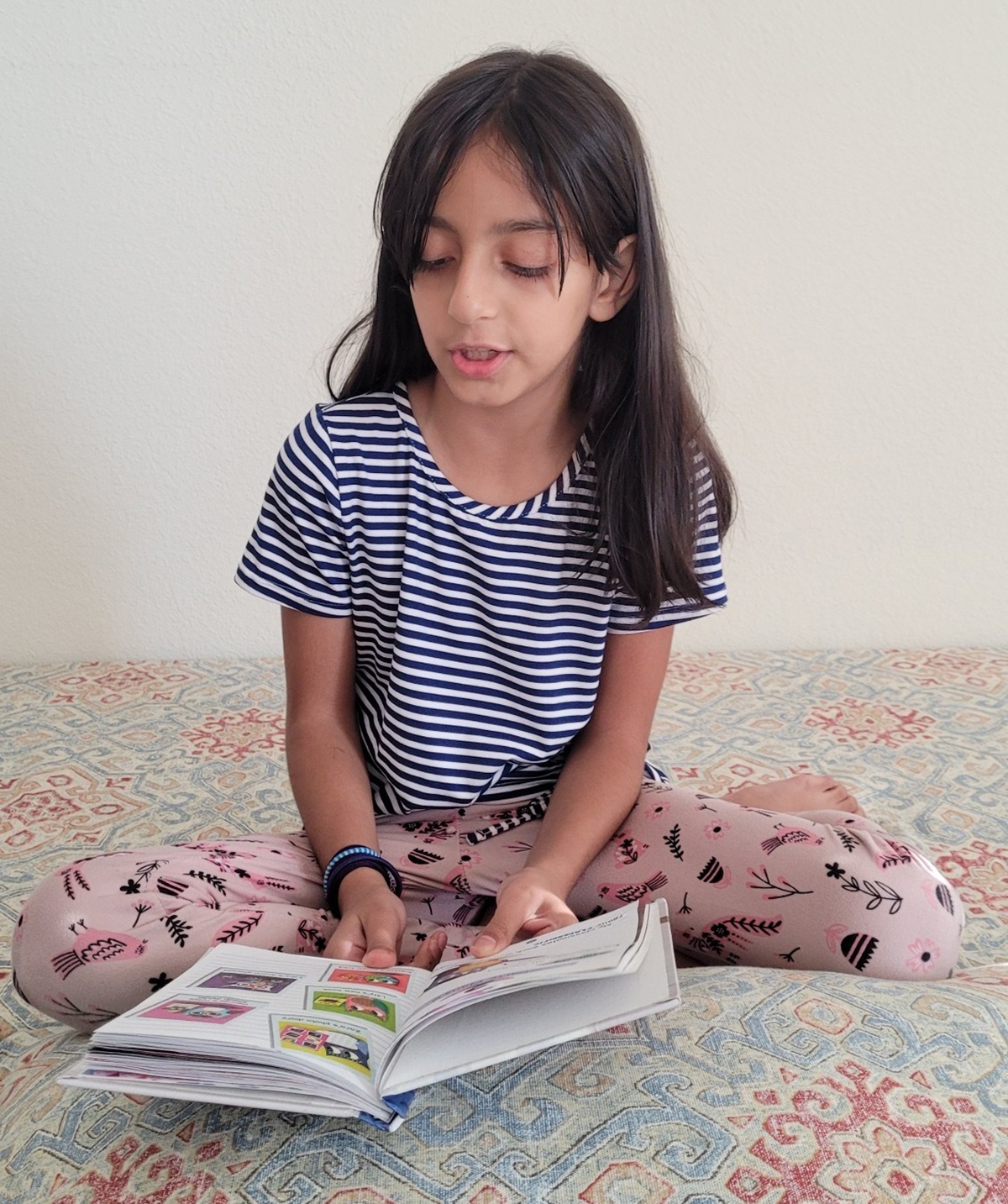

Young Afghan Refugees in America Adjust to New Norms — Especially for Girls

A year after the Taliban seized power, Afghan students who fled to the U.S., some with limited education, soak up culture, language and opportunity

By Jo Napolitano | September 11, 2022More than a year after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, plunging the nation into a humanitarian crisis in which girls have been forced from school and women from the workforce, thousands of young refugees who’ve fled the beleaguered nation are thriving inside American classrooms.

Roughly 85,000 Afghan nationals have arrived in the United States as part of Operation Allies Welcome, President Joe Biden’s August 2021 initiative to aid those who worked alongside American military personnel and who were forced to escape after the U.S.’s chaotic pullout.

It’s unclear how many of these refugees are school-aged but 44% of those held at U.S. military bases upon arrival last year were children — and more are en route, according to the Department of Homeland Security. They’ve landed everywhere from Fremont, California, to Northern Virginia where Afghan expats can be found in numbers.

Refugee resettlement workers and teachers alike say these students’ needs are unique: Some hail from highly educated families while others never before had the opportunity to attend school.

Many Afghan girls lag behind the boys — even their own siblings — and most, no matter their gender, trail their U.S. peers.

Despite this, their transformation has been remarkable, said Kathleen Renfroe, school liaison for the Fredericksburg Migration and Refugee Service office for Catholic Charities.

Renfroe enrolled between 120 and 140 Afghan children this past year alone. She said one student, a 14-year-old girl, was discouraged from attending school in Afghanistan — and in Virginia: The child was instead expected to marry and start a family, Renfroe said.

But school officials alerted her parents to compulsory education laws — and to their daughter’s potential.

“Cultural pressures can be difficult,” Renfroe said. “We helped them understand that here in this country, we encourage education and that it’s not a barrier to later becoming a wife and mother.”

In the end, not only was the teen excited about the possibility of furthering her education and prospering in a career of her choosing, but her mother was, too: She knew her daughter could achieve more here than she could at home, where girls are now being kept from school beyond their elementary years.

In another case, a child with spina bifida, who would likely receive no education in her home country because of her disability, has flourished in America: She recently completed a month-long STEM program that had all students learning about aerodynamics, computers and virtual simulations.

She was so thrilled to participate that she skipped breakfast every morning because she worried it would make her late to class, Renfroe learned through her mother.

“She had never seen her daughter so excited,” Renfroe said. “Her mom was really grateful. It was the first time she felt like a 12-year-old child.”

Texas

Nazia Sadat, a mother of three who lives with her family 30 minutes outside Houston, understands the joy that comes after a difficult transition.

Sadat does not speak English and neither did her children upon arrival in August 2021, making the last school year particularly difficult.

“All of them were very sad at the beginning to go to school,” Sadat said through a translator. “They couldn’t understand anything, but the teachers really helped them. They used Google Translate to understand what they said. They were loving, caring and helped them every day. In this one year, my children became very happy. They changed a lot from the beginning.”

A relative of hers, Kaynat Sadat, who lives nearby with her husband and three children, said her 7-year-old daughter Esra struggled with the loss of friends and family back home. All three kids clung to their mother and cried on and off throughout the day last summer.

School softened their loss, said Kaynat, who is fluent in five languages, including English. But even with her advanced education — she earned a law degree in Afghanistan in 2015 — Humble Independent School District’s policies were new to her and difficult to navigate.

“When we came, we didn’t know how the system worked,” she said. “But everyone was so helpful. In this one year, they never let us alone. The school asked about everything, gave every information — and we attended every program they had. I appreciate all they did for us. I feel I have a family here.”

Nazia Sadat’s children, who attend Fort Bend Independent School District, remember the difficulty of those early days in America, how they were unable to communicate with their classmates.

“When I first got here, I couldn’t talk to them,” said 11-year-old Mudasir, who also speaks Pashtu and Dari. “By wintertime, I was able. The kids are pretty friendly. If you say, ‘Can you play with me’, they will play with you.”

Asia, his 8-year-old sister, recalls being unable to answer what now seems like the simplest question.

“My friend asked me, ‘What is your name?’” she said. “I didn’t know what she meant.”

Now, the little girl has an American best friend.

“When we go to recess, we always play together and talk,” she said. “We sit on the swings and go play on the monkey bars.”

Nazia Sadat is hopeful her children will go on to college, that her son will make good on his pledge to become an engineer and that her daughter will pursue medicine.

“The main reason why I came here and am happy here is that I want my children to be educated,” Sadat said. “Especially my daughter.”

South Carolina

While she’s embraced American values, other families are reluctant to adapt to such a stark change.

Claudia Newbern, assistant principal at the Charleston County Newcomer Center in South Carolina, doesn’t want to lose Afghan students — particularly, girls — to the shock of the American school system.

Their interaction with men and boys back home is largely forbidden, so walking into a massive building filled with both goes against everything they’d been taught.

Newbern, careful not to rattle them so much that the students drop out, tries to familiarize them and their parents with their new surroundings: Some adjust easily while others struggle for months.

Three teenage sisters who arrived in the district in February were particularly distressed by the American system. They hail from a conservative family whose values clashed with their school’s.

“They were petrified,” Newbern said. “It was all very shocking for them.”

The district itself is enormous: It serves 49,000 students in 88 schools and specialized programs. Some 6,000 students are multilingual learners.

Recognizing their difficulty in navigating such a large school environment, the sisters were led around by a chaperone for much of their first two weeks on campus. And when they grew anxious around a male art teacher — he was friendly and accommodating but nevertheless such proximity made them uneasy — Newbern moved the trio to a class led by a woman.

It wasn’t the only unusual adjustment. The girls’ teachers had already asked male students to keep their distance during their first months of school, a request the boys were glad to honor: Newcomers themselves, they know how difficult it is to absorb foreign customs.

“We didn’t want them so overwhelmed that they didn’t go to school,” Newbern said.

The early accommodations paid off: The girls are thriving. While they are still struggling to learn English — they had only limited schooling at a young age — they are happy inside classrooms led by male teachers and interact with ease around all students, Newbern said, including the boys they once avoided.

All three want to attend college with two deciding on career fields. One plans to be a nurse and another a teacher.

And they make frequent use of a prayer room designed for those students who must pray during school hours.

The sisters are surrounded by their peers for much of the day but spend lunchtime in the library where they can sit on the floor, much as they would at home. Newbern was honored, recently, when the girls asked her to join them. It was an informative interaction: That’s how the administrator learned one of them, age 17, is married and that her husband remains back home.

“I asked, ‘Do you miss Afghanistan,’” she said. “They said, ‘A little. Here better.’”

The Taliban has kept most girls out of school beyond the sixth grade. Some secondary schools have recently and unofficially opened to them in the eastern part of the country, but their future remains uncertain.

College-age women also are under threat. Those who chose to continue with their studies must be segregated from their male peers. Protests have erupted over the restrictions but large-scale disruptions are too dangerous for participants.

Scholars at Risk, which promotes academic freedom around the world, has found that women have not been allowed on campus for wearing colorful hijabs, that scientific conferences and other programs are enforcing gender segregation and that some students have been attacked for not attending prayers.

The organization, launched at the University of Chicago in 1999, has relocated thousands of scholars to safer parts of the world through the years: It received more than 1,500 applications from Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover — including 20% from women. In a typical year, SAR receives 500-700 applications worldwide.

“To have restrictions around their ability to teach and/or research is an incredible loss — not only to women in Afghanistan, who have hard-won their academic accomplishments despite myriad pressures, but also to the academic community inside the country which will now be stifled and missing these vital voices,” said Rose Anderson, director for Protection Services at SAR.

Virginia

Tim Brannon, principal of the International Academy at Alexandria City Public Schools, said the number of Afghan students in his program has risen dramatically in the past five years: They accounted for roughly 25% of the population in 2017-18, but nearly half now, on par with Spanish-speaking students. The district currently serves 752 Afghans total — including 510 recent arrivals.

Brannon said the students, having seen the district honor its Latino population with cultural celebrations, asked that they have an opportunity to explain the Islamic holidays of Eid and Ramadan to their peers. During an April assembly, the students gave a brief presentation on Ramadan and did some traditional dances and, roughly a month later, shared a second presentation, teaching their classmates about the end of Ramadan and the celebration of Eid.

Brannon said the only discernible difference between Afghan students and their classmates is that the Afghan kids approach school officials as a group.

“When one kid has an issue, they come to the office as six,” he said. “They want to show up for their friends.”

The Afghan students’ presence, he added, has only made the school community richer.

“We have people from everywhere with all sorts of different backgrounds and experiences and they all bring something positive to this school,” he said. “It’s a chance for us to learn from — and about — somebody from a different culture and that adds to our knowledge of the world and our place in it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter