As Los Angeles Schools Combine Counselors for Foster, Homeless Students, Advocates Worry Services Will Suffer

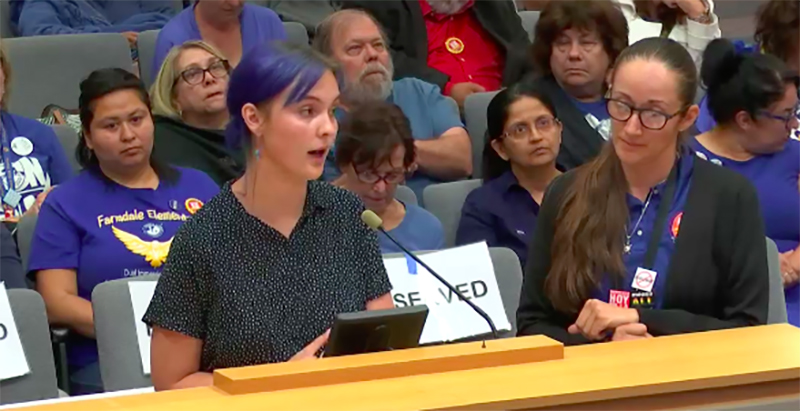

The Foster Youth Achievement Program has changed Skye Carbajal’s life. So the foster student left school early one day in late April to tell the L.A. Unified school board just that.

Standing at the podium during an April 23 meeting, Carbajal recounted her accomplishments since she’d joined the program two years ago: She’s attended a foster youth summit in Sacramento. Honed networking skills. Won a $20,000 scholarship for college.

“Without [my counselor], I would be without guidance,” Carbajal, who is heading into her senior year at San Pedro High School, told the board. “Without [my counselor], a year ago I would not have been able to talk to you today. I wouldn’t have the confidence to.”

Now, the five-year-old program, which focuses on foster youth school attendance, educational achievement and social-emotional well-being, is being restructured, despite vigorous opposition from foster youth advocates. The district is combining five specialized student programs together — including the Foster Youth Achievement Program and the Homeless Education Program — which officials say will streamline counseling services for L.A. Unified’s highest-need pupils by placing counselors at specific school sites, cutting down on travel time typically spent driving to schools across the district.

While district officials say intensive care for L.A. Unified’s nearly 8,700 foster youth is “not changing,” the program will no longer have its own designated counselors come August. It also remains unclear how many foster youth will stay with their previous counselor.

There are “no savings” from making these changes, district spokeswoman Barbara Jones wrote in an email on July 16. She confirmed that none of the 154 counselors across the five programs have been laid off.

The planned consolidation has sparked concerns among several advocacy groups, whose leaders have told school board members in at least three public meetings since April that the new model would bloat counselor caseloads, “dilute” services and upend current relationships between foster youth and their counselors. Such dilution was cited in a formal parent complaint filed July 11 that claims that L.A. Unified and its county overseers are not ensuring that more than $1 billion a year in targeted state funding is going to high-needs students — including foster youth.

Foster youth are considered one of the most vulnerable student populations. In California, they post some of the lowest academic scores, attendance and high school graduation rates of any student group attending public schools — though those numbers have been rising at L.A. Unified. Foster youth can face challenges such as emotional trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder, frequent school moves and an absence of healthy, trusting relationships.

“We’ve shared [with the district] … how impactful it has been to have this dedicated team to focus all of their expertise and all of their work for the success” of those students, Ruth Cusick, an education rights lawyer for Public Counsel, a pro bono law firm that’s advocating against the change, told LA School Report. “We’re very concerned about the level of support students who are foster youth will experience under the new model.”

Explaining the new model

The district is blending five separate programs — the Foster Youth Achievement Program, Homeless Education Program, Group Home Scholars Program, Juvenile Hall/Camp Returnee Program and Attendance Improvement Program — into a single “specialized” program, Pia Escudero, executive director of L.A. Unified’s Student Health and Human Services, told LA School Report.

That means counselors across those districtwide programs will now be pooled together and placed into local school networks, where they’ll serve the cumulative needs of foster youth, homeless students and students who have gone through the juvenile justice system.

There will be 150 masters-level counselors “out in the field” serving 29,056 students as of July 25, according to district counts. There are 8,668 students in the Foster Youth Achievement Program, 19,526 in the Homeless Education Program, 811 in the Group Home Scholars Program and 1,048 in the Juvenile Hall/Camp Returnee Program, which serves students who have been released from juvenile detention centers and are on probation.

(Some students are double counted in the data if they’re enrolled in more than one of the programs. The 29,056 students is the unduplicated count. The numbers “fluctuate and are based on the current enrollment,” Jones said.)

Last year, comparatively, the Foster Youth Achievement Program had about 80 counselors assigned to schools, according to the district. The Homeless Education Program, which Escudero said serves students in various housing scenarios who don’t all require intensive levels of care, had 19 counselors with no specific student caseloads in 2018-19.

A few goals of the restructuring, Escudero said, are to “reduce duplication of services” — which can happen when a student is enrolled in various programs that all have different counselors — and to “maximize the staff relationship with students in schools.”

Previously, counselors “spent a lot of time in their cars, finding parking, traveling from school to school,” Escudero said. “We’re going away from a model where a principal may have four or five counselors coming on campus to work with specific children, to really having this one person” attending to their needs. This streamlining, she added, will include placing one counselor with students from the same family.

These counselors will also track their assigned students’ attendance using a new data integration system. L.A. Unified continues to identify attendance as an area where improvement is critically needed. Chronic absenteeism rates have inched up in recent years, with 15.1 percent of district students missing 16 or more days of school in 2017-18. The district loses about $62 million in funding annually from chronic absenteeism, Jones said.

Although the programs are being combined, funding for each remains the same, Jones said. The Foster Youth Achievement Program is budgeted at about $15 million for the 2019-20 year.

Some staff, such as those working with “high-end homeless populations for emergency services,” will remain in their roles separately, Escudero said. There wasn’t a staff count available.

Advocates’ take: ‘A pretty untenable plan’

Advocates have sounded the alarm about the size of counselor caseloads under the new model.

As the Foster Youth Achievement Program merges into this larger program, the number of counselors serving foster youth at the school level is growing by 88 percent, from about 80 to 150 counselors. But the number of students being served is simultaneously swelling more than 230 percent, from nearly 8,700 foster youth to some 29,000 students across all of the programs.

The highest counselor caseload assigned as of July was 147 students, Escudero said. Estimates of the Foster Youth Achievement Program’s average caseload before the restructuring vary; advocates cited a roughly 70-student caseload in 2018-19, while a May report in The Chronicle of Social Change, citing L.A. Unified staff, put the number at 60 foster students per counselor at the high school level and 100 at the middle school level.

For advocates like Jessenia Reyes, the manager for educational equity at Advancement Project California, a central concern is a dilution of services for foster youth as counselors juggle more students and their individualized needs. “Whole child care does not happen when we reduce quality time” for students, she told the board at a June 11 meeting.

Public Counsel’s Cusick agrees. “We think it’s a pretty untenable plan to ask our counselors to serve all of these different [group] needs,” she told LA School Report.

When asked about advocates’ concerns with caseloads, Escudero said it’s more complex than an average ratio. Counselors’ caseloads will reflect the level of student need within a school network, she said; a larger caseload, for example, would include many non-foster students who don’t require extensive attention. While all foster youth will continue to receive the highest level of care available, there will be triage for the other student groups to identify the scope of their needs, she said.

Many district-identified homeless students “are doubled up with family members, some of them are living in garages and other types of housing” and don’t meet the federal definition of homeless, Escudero said. “Many of them do not need intensive services … [We’re focusing on]: Who is not coming to school? Who has had a report of not being on track to graduate?”

Still, many advocates are questioning why the district is fixing a system they don’t see as broken.

Foster youth attendance at L.A. Unified has been improving while the graduation rate is rising. Between the 2016-17 and 2017-18 school years alone, the percentage of foster students with 96 percent or better attendance rose from 49.3 percent to 55 percent. The graduation rate also rose, from 47.2 percent to 52.1 percent — the largest jump of any student subgroup that year.

Foster achievement reporting is now mandated under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015. L.A. Unified will also start producing reports that include the number of district students in foster care, how often they change schools and how they are doing academically, socially and emotionally after the 2019-20 year, thanks to a May resolution from board member Kelly Gonez.

Advocates have touted the role of “consistent” adult support in foster youth’s successes. Some pleaded at meetings this year to keep students with their current counselors.

“The value in this program has to do really with connections built between counselor and student and caregiver,” Traci Williams, a Foster Youth Achievement Program counselor, told the board in April. “And without us remaining in the structure that we are currently, that relationship will likely dissolve.” Williams declined to provide further comment to LA School Report with the realignment “already in progress.”

Carbajal, who is one of Williams’s students, also spoke to the importance of these connections. “I have built a relationship with her that has helped me through so many difficult times,” she said — dealing with social workers, going to court. “Foster youth like me and so many others deserve the consistency and support that the [Foster Youth Achievement Program] offers.”

Escudero said the district is in the process of doing assignments now, and “if there’s a specific counselor that has a relationship with a specific school for a long time, we’re trying to honor those assignments.” She added that there “absolutely” will be professional development for counselors. “My hope is once [counselors] get their assignment we can dig into … providing very thorough support to children,” she said.

In an email to LA School Report, board member Gonez said her team is monitoring the restructuring — and encouraging conversations between the district and the community.

“We can and should have collaborative conversations with community stakeholders about how to best ensure our programs are responsive to the needs of students and our schools,” she said. “My office has been working closely with our District staff, as well as partner organizations, to monitor the progress of those conversations.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)