Analysis: How 100 Large Urban Districts Are Wrapping Family & Community Input into Plans for Spending Federal Emergency School Relief Funds

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As school districts prepare for the 2021-22 school year, federal dollars from the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER) present the potential for helping students and communities recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, and for making major, lasting improvements.

Districts have wide latitude in how they will use the funds, with one clear mandate: that they engage in “meaningful consultation” with their communities and factor this input into spending choices.

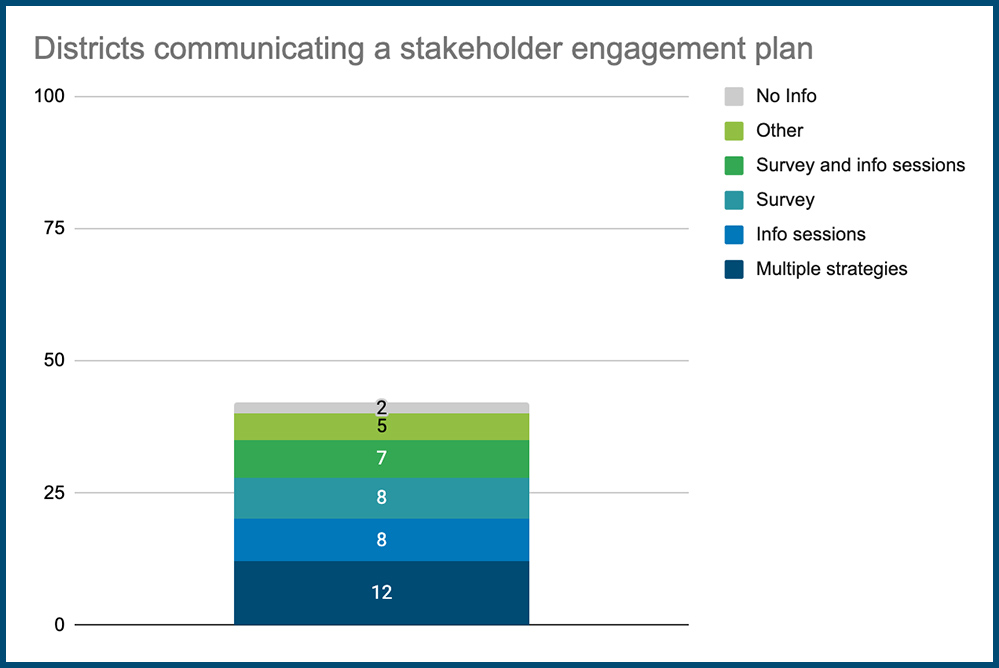

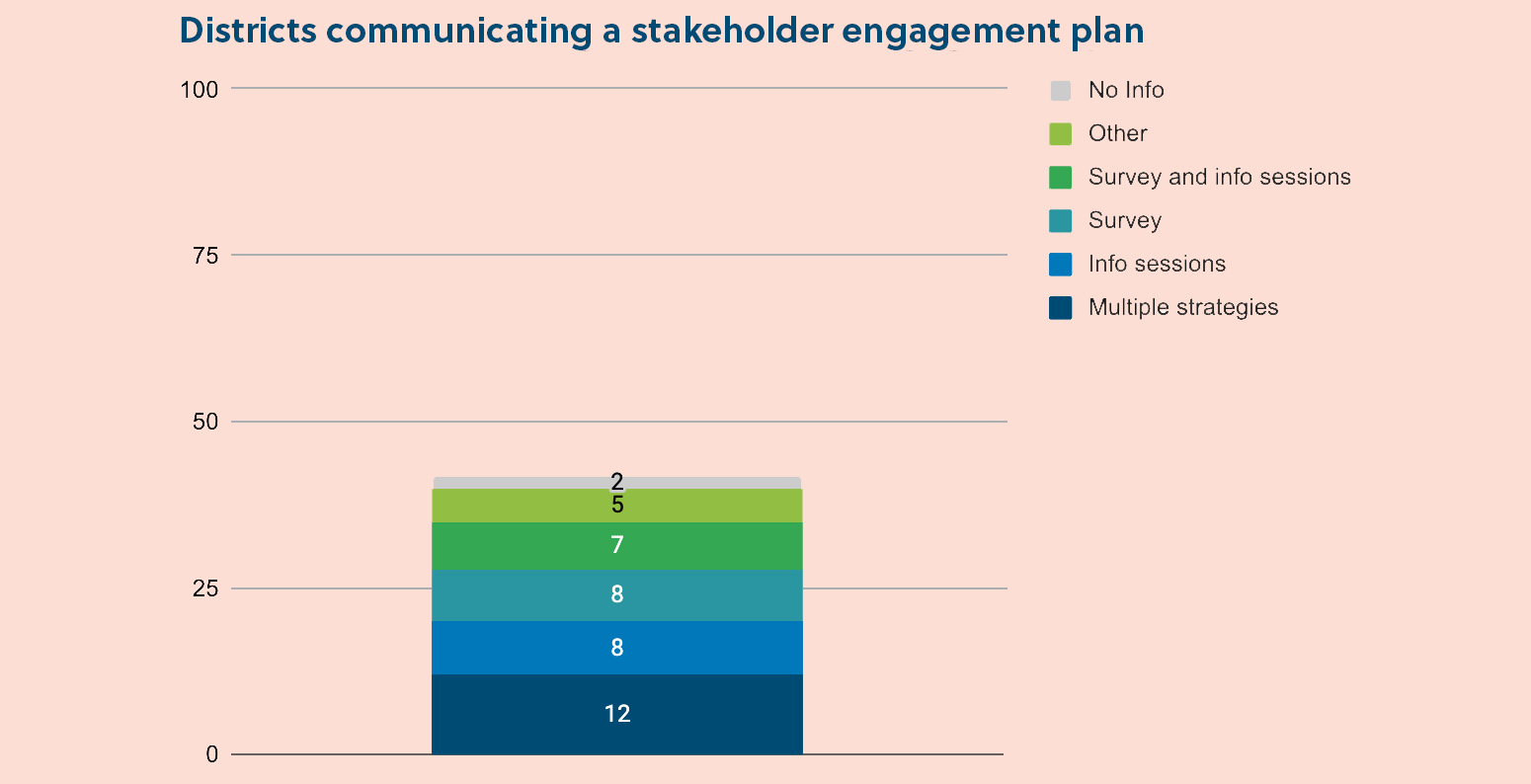

Our first look at ESSER priorities indicated many districts may be struggling to reconcile public input with their own strategic priorities, and that less than half of the 100 large, urban districts in our database have posted plans for collecting community input.

We took a deeper look at what large, urban districts are doing to engage communities, what input they’re receiving and how it appears to be shaping their decisions. While about half the districts in our review have not publicly detailed their process for gathering public input, even fewer have been transparent about how they are responding to feedback. Just 13 are sharing the feedback they’re receiving.

In the few districts that do share comments or survey results, we see some common trends. Parents and district staff say they prioritize support for vulnerable students, investments in teacher capacity and flexible virtual school options. These have not been priorities in many districts.

We also found a few that adjusted plans in response to public feedback and a handful that are committing a portion of ESSER funds to strengthening community engagement for the long term.

Ultimately, districts have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to adopt responsive plans that reflect community needs, promote student achievement and build lasting trust in their decisionmaking. Truly transparent community engagement around how they spend money remains a work in progress — both for the immediate task of allocating federal pandemic relief funding and into the future.

Public engagement strategies vary widely, but many districts aren’t clear about plans

The American Rescue Plan Act gives districts three months to gather input, almost entirely over the summer, when children are out of class and families may not be paying close attention to communication from their schools. Given this context, one would expect to see more public outreach to ensure families are aware of opportunities to weigh in. While we found some exemplary efforts to engage communities, it remains unclear how most districts plan to meet the requirement for meaningful consultation.

The law allows districts to decide how to conduct outreach and what to do with the input they receive. Of the 100 in our database, 47 have a public plan in place for consulting their communities on how they plan to spend ESSER funds — a surprise, given the statutory requirement. Of these 47 districts, 22 are providing at least two methods of community engagement, including surveys and information sessions.

Districts are using diverse outreach strategies. In Boston Public Schools, engagement began with roundtable discussions and continued with review-and-comment periods. In Boulder Valley, Colorado, online forums allow parents to post suggestions that other community members can support with a heart-shaped icon.

In Atlanta Public Schools, parent feedback has already shaped plans for the fall. After families pushed back on a proposed half-hour earlier start time for elementary schools, the district chose to add 15 minutes to either end of the school day.

Districts working to reconcile competing priorities may find that leaders of individual schools can better accommodate family and student needs. Chicago Public Schools, for example, is providing $160 million in flexible funds to principals over the next two years, giving them discretion on budget priorities. The money will be distributed based on a new Unfinished Learning School Investment Index, which identifies schools that need the most financial support for their students. Decentralized funding strategies also offer opportunities for individual schools to develop systematic approaches for collecting community input.

Some districts plan to invest in long term engagement improvements

About a fifth of districts (21 percent) communicate their intent to invest ESSER dollars in amplifying family and community engagement long term. This includes Chicago Public Schools, which is providing 75 schools with multigenerational, culturally responsive programming for parents, grandparents and other caregivers to support literacy development, and Detroit Public Schools Community District, which is putting funds toward re-engagement strategies such as home visits and parent outreach coordinators.

Buffalo Public Schools in New York has identified six strategies to bolster family and community engagement, using data collected in previous parent involvement surveys. Working with stakeholders, the district will adopt a districtwide, research-based framework to strengthen “effective family and community engagement linked to improved student achievement and other outcomes.” It also plans to partner with community-based organizations to conduct ongoing, culturally relevant training and feedback sessions for school personnel, and to identify, train, develop and support grassroots teams of family and community members to help mentor and reach out to other families.

Buffalo’s plan explicitly states its intention of building mutual trust, promoting partnership with families and communities and understanding how they can help support education. Long-term district engagement efforts such as these are necessary to strengthen trust and relationships between districts and families, as school staff build a longer track record of listening and responding to stakeholders’ needs.

Early survey results show stakeholders prioritize support for vulnerable students, teacher capacity and more virtual learning options

Likely due to the vague nature of “meaningful consultation,” district reports on survey data remain sparse.The 13 districts that report this information release it in diverse formats, such as a comprehensive report in Baltimore City Schools, stakeholder-specific reports in Houston Independent School District and racially disaggregated survey results in Austin Independent School District.

Early survey reports show parents and other stakeholders prioritize supporting vulnerable and historically marginalized student populations. Des Moines Public Schools attaches time-sensitive goals to priorities of early literacy and algebra proficiency, with an emphasis on closing racial gaps. Goals include increasing the reading proficiency of third-grade Black males from 35 to 72 percent by June 2023, and doubling the percentage of Black male students earning a ‘B’ average or better by the end of ninth grade over the next two years.

In San Francisco Unified School District, a report from family advisory groups expressed concern over insufficient supports for students with disabilities and those identified as English learners. One parent stated that their child did not have the chance to practice speaking English for an entire year during the pandemic.

Published comments and surveys in several districts advocate investments in teachers. It’s worth noting that results in some districts combine input from parents, community members and school system employees, and don’t break out results for these groups, as Baltimore City has done.

In Boulder Valley School District, the seven most popular comments on its online forum ask for reducing class sizes, maintaining substitute teacher pay and hiring additional full-time personnel. Survey respondents in Austin indicated they want ESSER funds to compensate teachers for extra work associated with increased staff expectations for morning planning and afterschool enrichment.

Families are telling districts they prefer flexibility in school options. Nearly 1 in 4 Austin respondents said they may opt in to a virtual model — results that align with similar surveys conducted by other districts. Some Baltimore City families expressed interest in virtual learning options. San Francisco’s Joint Advisories Report demands reliable access to technology and internet for all students.

Districts must explain how stakeholder preference drives investment strategies

While this early sampling of public input in a small number of districts may not be representative, the preferences surfacing do not all align with the stated ESSER priorities of districts in our review. Districts are emphasizing spending to address student learning loss and support students’ social and emotional well-being, and at least 41 have committed to continuing a virtual learning option next school year. However, just 14 percent of districts in our review have communicated a commitment to strengthening support for English learners, 23 percent to better serving students with special needs and 37 percent to investing in teacher capacity.

Districts have broad license to determine what “meaningful” consultation entails, but the ultimate test will be how well their spending decisions align with the stated preferences of the communities they serve. Achieving this alignment will be no simple feat. Districts have to build plans on a short timeline this summer, while balancing potentially conflicting input from different stakeholders, focusing on their students’ immediate needs and avoiding unsustainable funding commitments.

This moment demands that districts not make financial decisions in a vacuum. Those that treat the meaningful engagement mandate as a mere compliance exercise run the risk of spending money in ways that do not address student, family and staff needs.

It’s not too late for districts to embrace these principles as they finalize their stimulus plans, build their fall budgets and adjust decisions in the years and months to come:

1. Offer a wide range of public input options. Districts must go beyond just one mechanism or strategy. An online survey could be paired with in-person town halls. Input meetings should be held not just in a centralized forum at the district office, but also at local schools.

2. Use a clear, inclusive data collection strategy. Data is only as powerful as it can be seen and processed. Districts that expect to hear from diverse stakeholders through a variety of channels, like community forums and online surveys, must have a strategy to review and process this data in a way that faithfully reflects both the broad themes and the potential tensions in that input. Districts should also consider employing community members to review and interpret these results alongside district staff.

3. Explore participatory budgeting processes. In meeting the spirit of the requirement for “meaningful consultation” with community members, districts should explore permanently giving families more input into the annual budgeting process, and not just on ESSER spending. Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab provides a simple survey template that districts can use to gather community input to inform decisionmaking.

4. Publish public input results. Members of the community should be able to see how their input shapes district decisions. Transparently sharing survey results and comments, as the 13 districts in our review that published feedback have done, demonstrates a desire to hold districts accountable to the community for their actions.

5. Invest in ongoing engagement. Districts will be investing their federal funds for the next three years, and this summer’s should be the first of many public input cycles. Districts should invest some of these dollars in ongoing data collection, review and reporting to continue to keep the public engaged in their decisionmaking processes.

If members of the public can see that their input can have an impact, they may be more likely to trust their local school systems. A modest investment in that trust could go a long way toward rebuilding school systems that are responsive to the needs of families and communities.

Alvin Makori is a junior research assistant at the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

Bree Dusseault is practitioner-in-residence at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, supporting its analysis of district and charter responses to COVID-19. She previously served as executive director of Green Dot Public Schools Washington, executive director of pK-12 schools for Seattle Public Schools, a researcher at CRPE, and as a principal and teacher.

Travis Pillow is a senior fellow at the Center on Reinventing Public Education and former editor of redefinED, a website chronicling the new definition of public education in Florida and elsewhere.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)