Analysis: Most Students in Urban Districts Will Have Summer Learning Options, But Schools’ Plans May Miss the Mark

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

In April, when the Centers on Reinventing Public Education conducted an initial review of large urban districts’ summer plans, slightly more than half had not shared any information at all, and of those that had, nearly two-thirds were missing critical components like tutoring, assessment and communication plans. The situation has changed dramatically in the last two months; our latest review found that 97 of 100 reviewed districts have now announced some form of summer school programming.

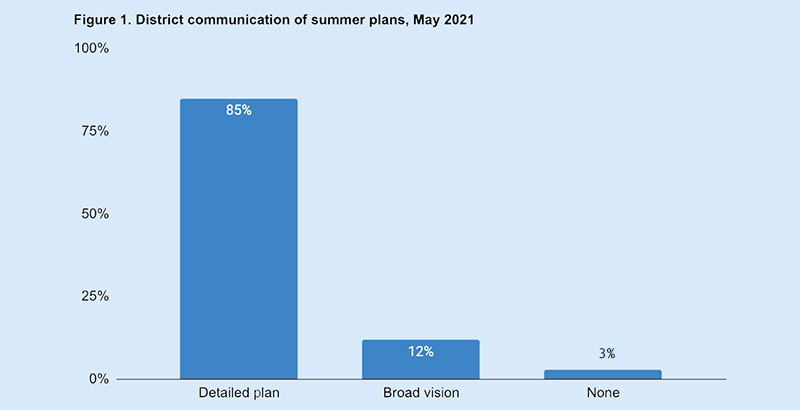

As of May, the majority of the districts — 85 percent — shared detailed plans on their summer learning programs, up from 35 percent in April and 32 percent at this point last year. In addition, 12 districts articulated a broad vision. Only three of the 100 districts have yet to share a vision or plan.

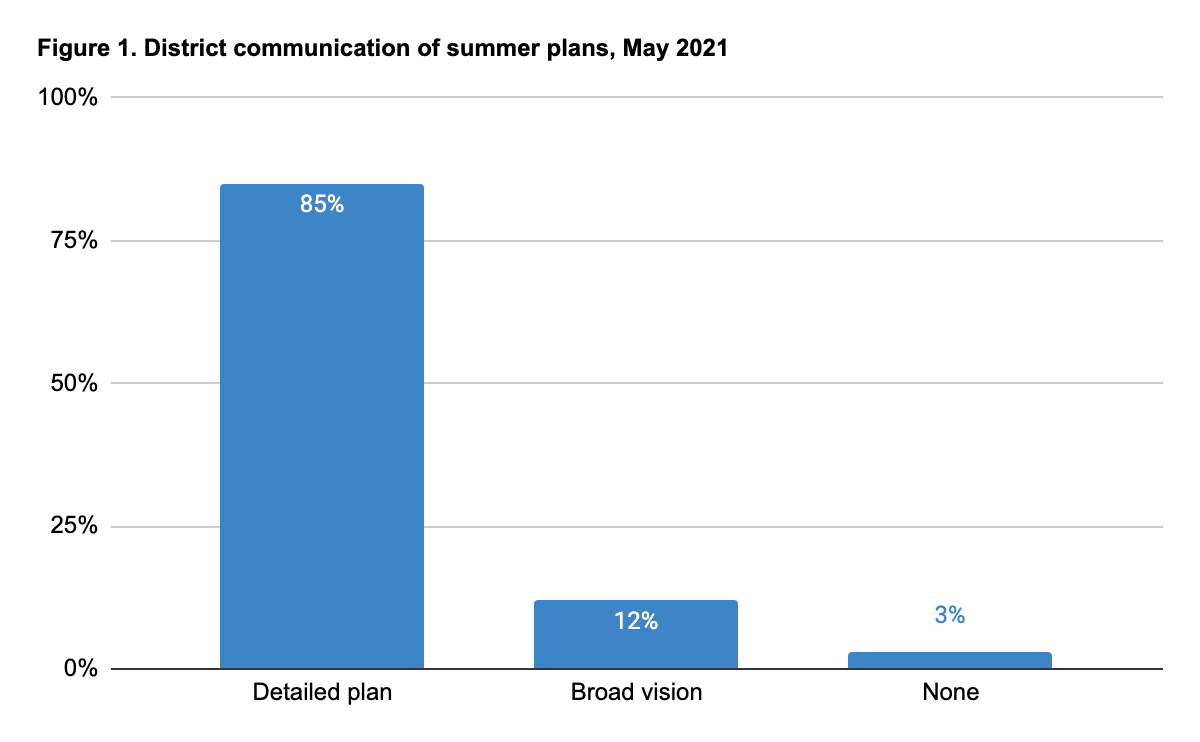

The number of districts detailing both in-person and remote learning options has increased from 13 percent to 46 percent since our April survey; in-person-only options have increased from 8 percent to 29 percent. A handful of districts (5 percent) are offering remote-only instruction this summer.

Of the 81 districts that included duration in their released plans, their programs will provide on average approximately five weeks (25 days) of summer learning and enrichment. This is on par with the pre-pandemic recommended five-week minimum of programming to maximize effectiveness. While this is promising, we question whether five weeks will be enough, given the tumult and disruption of the last year and a half for many students.

Forty-four of the 100 districts will offer less than 25 days of summer learning. This, layered with the typical challenges of enrolling students and maintaining high attendance, may mean that program duration is not sufficient to truly accelerate learning for fall 2021.

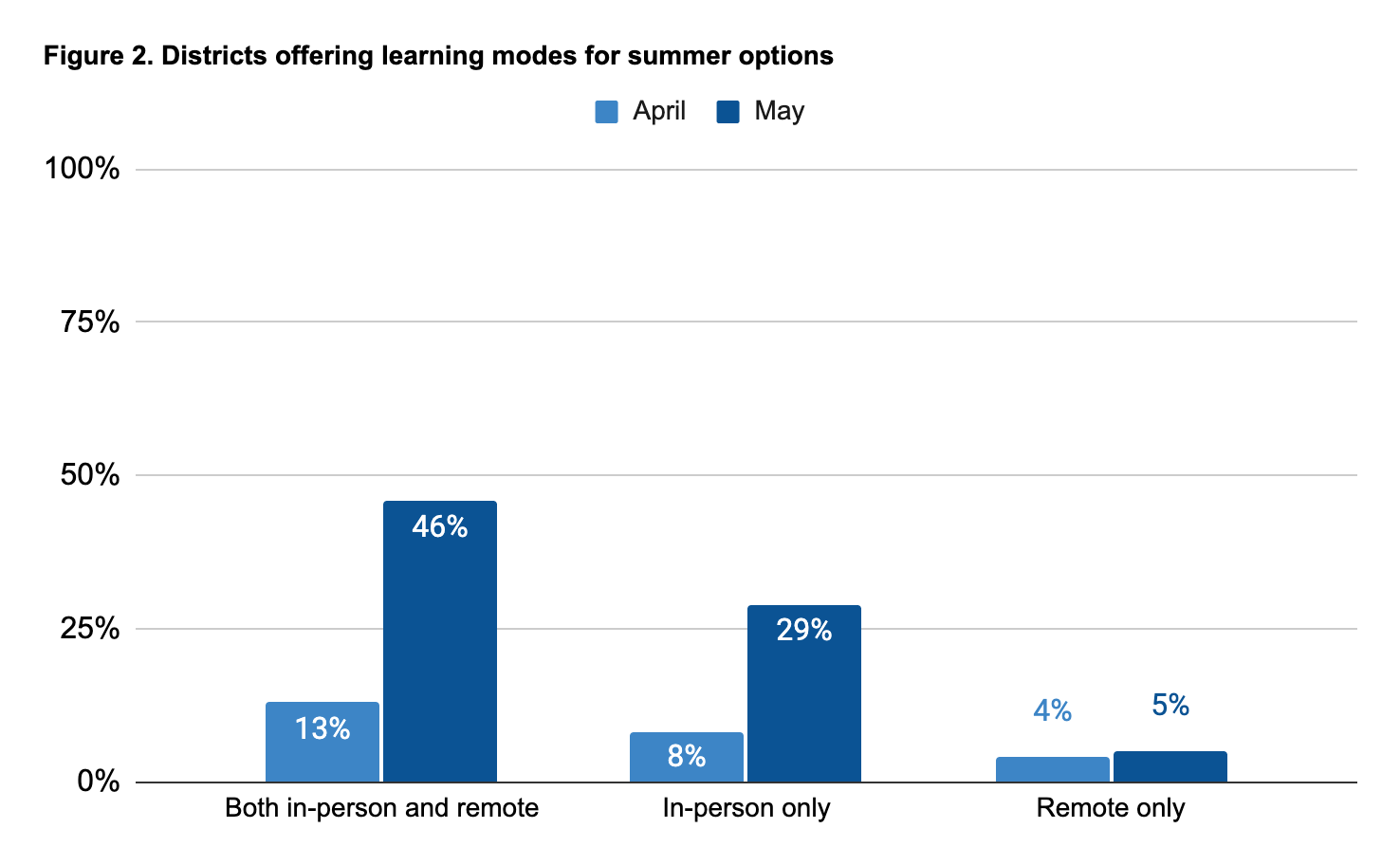

Most districts we surveyed are focused on reengagement through enrichment but lack personalized programming for vulnerable learners. Of the 100 districts, 78 percent have been explicit about offering summer enrichment opportunities, 73 percent about credit recovery and 71 percent about support in math and English language arts.

While there’s a strong emphasis on general learning and enrichment plans for K-12 students, relatively few districts outlined how they will triage to meet the needs of particularly vulnerable student groups. For example, less than half (45 percent) of the districts are offering summer bridge programs for those critical early and middle transition years from preschool to kindergarten, elementary to middle school and middle to high school.

It’s good to see districts taking a balanced approach to blending enrichment and academics. After a very difficult year, students need social activities and fun in tandem with academic support. Recent guidance notes that, when structured appropriately to protect academic learning time, enrichment activities can reduce opportunity gaps and increase attendance rates, and many of the districts are collaborating with community organizations to expand enrichment activities:

- Miami-Dade County Public Schools is partnering with multiple organizations to offer programming at 179 of 350 schools, helping to reach its goal of serving 65,000 students. The district’s strategy is to combine county-based academic support through summer programs typically funded by a local nonprofit partner, The Children’s Trust.

- San Francisco Unified School District is building a coalition of community organizations, nonprofits and business leaders to expand existing programs to new sites, offer remote-learning credit recovery options and provide opportunities to take career and technical courses with a paid internship.

- Oakland REACH City-Wide Virtual Hub connects families with the day-to-day education of their children by empowering parents as advocates and influencers in virtual education in the summer and fall. It works to connect families with educational services through liaisons and multilingual services.

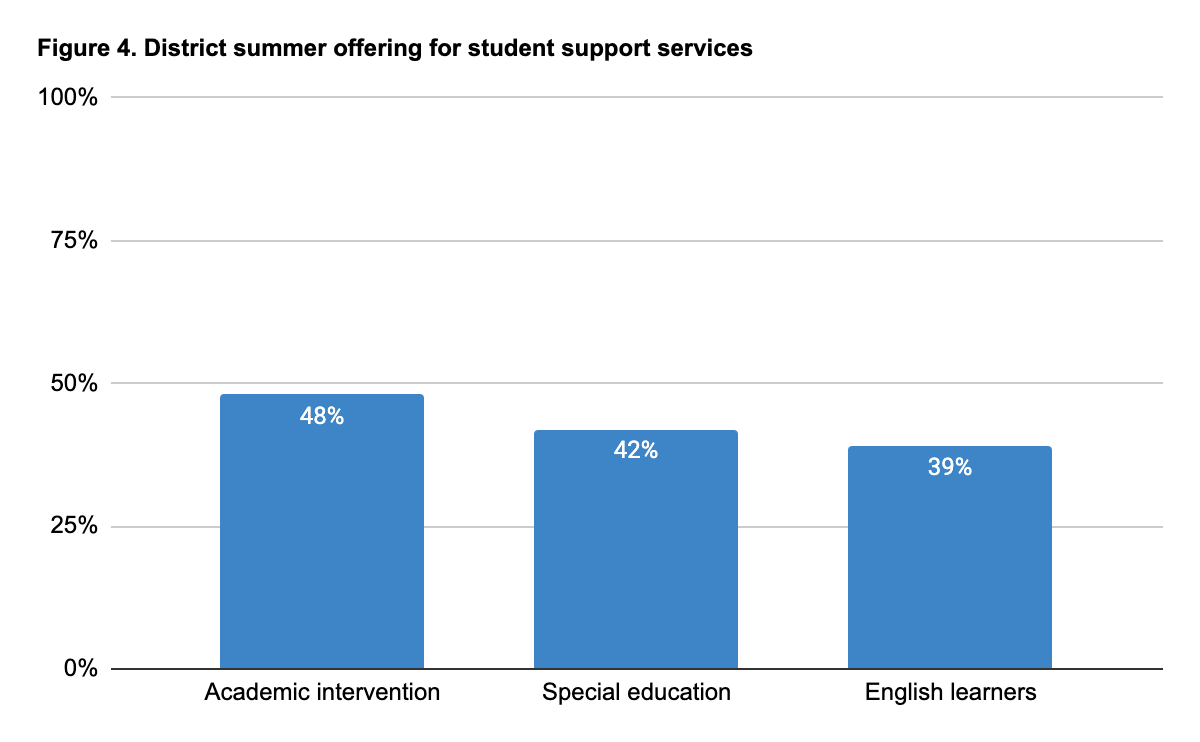

However, the number of districts offering specialized services for multilingual and special education students is relatively low. Just 39 percent will have programs for English learners, 42 percent for students receiving special ed services. A recent NWEA study found summer learning losses were much greater for students who received special education interventions at any point during school than those who never have; districts should increase and improve summer programs for students with disabilities and other children who face similar vulnerabilities in accessing grade-level content in the fall. Without accounting for the personal needs of those students over the summer, many of the most vulnerable children will be starting fall 2021 less prepared than their peers.

Of the 100 districts reviewed, only 48 percent said they were offering summer learning programming specifically for students in need of academic intervention. That low number is concerning, as is the fact that many districts do not seem prepared to assess students’ levels and needs as they enter summer programs. Only one-third are providing specific information about how they are identifying students as being “in need of academic intervention” this summer. Six are relying solely on standardized assessment data, 11 are using a mixture of assessment data, grades and attendance, and 14 will take prior grades into account, while others will use measures such as whether students failed courses or met promotion standards. The majority — 69 districts — did not specify anything about how they plan to assess the need for academic intervention this summer.

This reveals that districts may be relying on traditional remediation, based on subjective views of student achievement, rather than acceleration strategies based on diagnostic or interim assessment data and the standards necessary for accessing grade-level content for next year. Another possibility is that districts are using summer programming more for social and emotional learning and enrichment, with a view toward returning to academics in the fall.

Compared with this time last summer, when only a quarter of large and urban districts reviewed by CRPE were offering summer learning and enrichment plans, it is notable that 97 percent of districts reviewed now offer summer options. These expanded plans are a step in the right direction for reengaging students and working toward learning recovery. Last year, CRPE noted that summer programs would ideally be aligned with long-term learning recovery plans. This is a reasonable approach to summer planning, but we didn’t quite see that type of strategic thinking during the 2020-21 school year. While summer programs are ready to roll for this year, there are a few ways that districts can consider reengaging students more consistently and building cohesion between summer and fall learning:

- Ensure consistent attendance and engagement. Attendance and engagement in summer programming is a common challenge. There are opportunities for districts to use Academic Recovery Plan stimulus funds to expand the number of summer learning seats so more students can attend. This seems especially important given recent data suggesting underreported absenteeism rates this year. For example, Guilford County Schools, in Greensboro, North Carolina, has increased enrollment for its summer programs from 1,200 students in 2019 to 8,000 this year by using a blend of assessment data and teacher and parent recommendations to establish a list of invitees to multiple sessions. That said, there is no certainty that students will show up. Some researchers suggest that sharing explicit expectations about student attendance before registration improves the likelihood that students who sign up will come; however, it is important to balance such practices with incentives and efforts to remove barriers (for example, paying students who may be missing out on summer job earnings). Overall, attendance will improve when educators prioritize meaningful relationships and communication plans for students and families.

It is also critical that summer programs be made easier to attend. For example, parents may rely on programs that align with their work schedules (e.g., full-day versus half-day). Uniquely, the Arlington Independent School District, outside Dallas, is offering three sessions to let students choose “their summer learning experience.” This type of expanded offering may improve enrollment and attendance, leading to better reengagement for fall. But when students do make it in the door, it is also important that programming, especially academic interventions, is aligned to their needs and interests. A study of Project READS suggests that sending home books matched to reading level and interest, coupled with high-quality instruction and incentives, results in improvements in reading performance.

- Recruit high-quality, motivated teachers. It is no secret that this year heaped layer upon layer of challenges on classroom teachers. Some have predicted that teachers may be too tired to sign on to summer teaching positions, so districts are using new methods to fill the gaps, like partnering with community organizations, hiring retired teachers or increasing pay. Fort Worth Independent School District is providing literacy training to community partners teaching reading; Miami Dade is paying teachers $1,000 bonuses on top of their base compensation; and the Indianapolis Teaching Fellows programming will supplement staffing in that district’s schools.

- Combine summer programs with long-term learning recovery plans. Summer is short, and many families, teachers and principals are exhausted. For this reason, districts must combine summer plans and long-term educational strategies in one coherent vision for learning recovery. Initial academic gains level out for students who are moderately engaged during summer learning — but when students regularly attend (20 or more days each summer) for two years, they outperform their peers on math and reading assessments.

To ensure programs are available, districts can leverage federal COVID relief dollars to expand capacity and consistency among programs. Maine’s Portland Public Schools outlined how it is using Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds to add seats and diversify offerings from school, district and partner summer programs. The North Carolina legislature is supporting district plans by providing tutoring scholarships through the $170 million Summer Success Program. Parents in that state can apply for scholarships ranging from $1,000 to $3,000 to access tutoring, camps or mental health services.

Expanded summer learning and enrichment plans are necessary to reengage students for fall and to begin to address unfinished learning and social, emotional and mental well-being. Districts can strengthen their summer plans by reinforcing attendance and engagement strategies, offering non-traditional recruitment and pay for high-quality, motivated teachers and integrating summer programs into learning recovery and acceleration plans.

Christine Pitts is an educator and researcher working with teachers, families and policymakers across the U.S. You can find her on Twitter @cmtpitts.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)