Districts Seek ‘Meaningful’ Engagement on Spending $122 Billion in K-12 Relief Funds, But Some Parents Say They’re Taking Shortcuts

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

With three children in Arizona’s Mesa Public Schools, Krista Puruhito has a vested interest in how the district plans to spend its $160 million in federal relief funds. When the district held a series of community budget meetings in May, she was among the more than 300 participants who voiced requests ranging from water bottle filling stations to more teaching assistants in the classroom.

Puruhito also wants to see expanded arts integration and afterschool enrichment programs — especially in communities where families can’t afford such extras.

“They shouldn’t be directing this to all the high-income schools that already have $100,000 in their PTOs,” she said.

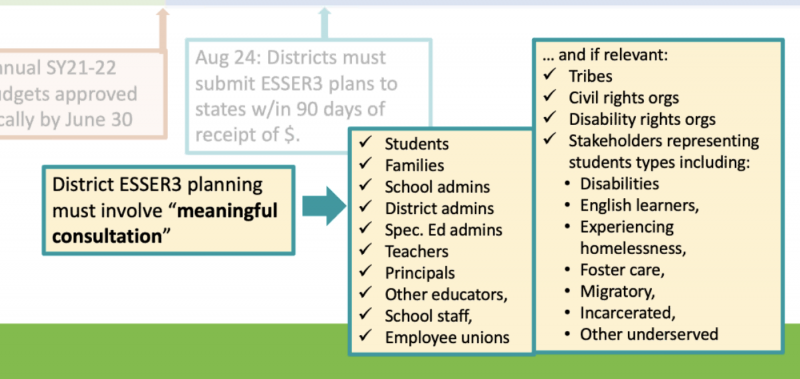

Mesa, like every other district across the country, is required to undertake what the American Rescue Plan calls “meaningful consultation” with community members over how to spend $122 billion for K-12 before October 2024. Some districts are taking extensive steps to reach out to their communities, providing translation during virtual meetings and posting updates on how the money will be used. But leaders say it’s challenging to balance competing interests and some parents feel districts have taken shortcuts.

A 100-district analysis from the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington, to be released Wednesday, shows that just over a third of districts have posted details about how they’re involving the public in designing their plans.

“This is surprising given this is a mandated expectation for receiving funds,” said Bree Dusseault, a practitioner-in-residence at the center.

With remote learning giving parents a stronger role in their children’s education over the past year, advocacy groups across the country have pressed for broad participation from diverse groups of parents, and for multiple opportunities to inform decisions about how the money is spent.

“We have been really pushing back against the idea that surveys are enough to check the box. It’s just not enough,” said Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union. “Where we have parent power on the ground, our expectation is that we have a seat at the table.”

But will they be OK with the limits on that power? “A lot of people can’t tell the difference between engagement and decision making,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “Listening to you and doing what you want are two very different things.”

The law initially gave districts three months to collect input and submit plans to their states, but AASA and the 19-member Large Countywide and Suburban District Consortium asked the U.S. Department of Education for more flexibility. The department agreed that districts could take longer to submit their plans as long as they were completed within a reasonable amount of time.

Owning ‘the final product’

The Center’s review highlights a few examples of what researchers call more “robust” examples of community engagement. The Baltimore City Public Schools is posting the results of surveys and input sessions online, and the Boston Public Schools, which is making plans to spend $400 million in relief funds, created a separate commission to lead the process.

“When you have a lot of money, it’s often harder to spend,” Boston Superintendent Brenda Cassellius said in an interview, adding that she’s drawing on 10 years of experience as Minnesota’s education commissioner to give the public an opportunity to “own the final product.”

Over the course of six meetings — translated into at least eight languages — over 1,200 community members participated. The district released a draft of its plan last week and will continue to collect feedback.

“It’s forced us to think about what investments pay dividends over time,” said Chris Smith, executive director of Boston After School and Beyond and a member of the commission.

Some of the funding will be spent on facility improvements to “show to the city what’s been missing for so long and what needs to continue,” Cassellius said. “We have schools without cafeterias, science labs, libraries.”

But another priority was getting funds to local schools as quickly as possible. The commission agreed to allocate the money to schools based on how many low-income students, English learners and students with disabilities they serve.

In Virginia, meanwhile, a June public hearing held by Fairfax County Public Schools provided a glimpse into how challenging it might be for district leaders to balance requests from different parties. Kimberly Adams, president of the local teachers union, argued for raises and bonuses for those who taught in person last school year.

“We’ve continued to lose ground in recruitment and retention,” she said. The district canceled summer school for hundreds of students with disabilities because of a shortage of teachers and the district froze salaries in last year’s budget.

But Eileen Chollet, the parent of a student with special needs, said the district should be reimbursing families who spent money on therapists and private tutoring because their children missed out on services during remote learning.

“My daughter, like all the other children in this county, needs help now,” she said.

‘Time and input’

In Minnesota, parent advocate Khulia Pringle helped organize a virtual town hall for the Minneapolis Public Schools and wanted to do the same in neighboring St. Paul. Leaders were already in the midst of holding community forums, but added another with Pringle as a co-moderator.

“I let everyone know that this was rushed, and I didn’t like the process,” Pringle said.

Stacey Gray Akyea, the district’s director of research, evaluation and assessment, agreed the timeline for getting community input was short — from June 17-28. But she said there will be more opportunities for parents to provide feedback. While most TItle I schools are experienced at gathering parent input, Akyea said this level of engagement may be new for some districts.

“As a researcher, I feel strongly that we [shouldn’t] ask people to give their time and input without using it,” she said, adding that she told Pringle she would ensure parents would have additional opportunities to be heard. The district is now translating its report based on community input into four languages.

Typically, parents who are already plugged into district issues are more likely to be aware of opportunities to make recommendations on major initiatives.

“You work your way up the ladder,” said Puruhito, who took part in forums when the Mesa district was searching for a new superintendent. “If you participated in one, you get invited to more.”

But planning to spend what leaders have called a once-in-generation influx of federal dollars on K-12 schools is being held on a national scale and with specific expectations that districts will reach students, parents, unions, administrators, civil rights groups and others.

“Parents want school to look different and be more engaging,” Holly Williams, Mesa’s associate superintendent, said of the district’s meetings with parents. Surprisingly, she said she didn’t hear a lot of concerns about learning loss. “They weren’t worried that their kids didn’t know algebra. They were worried their kids didn’t have connections.”

Academic recovery is one of the ways districts are required to spend a large chunk — 20 percent — of their funds. Summer school, extending the school day and one-on-one tutoring are among the approaches districts are using. But community feedback in Atlanta shows that even a pandemic is not enough of a reason to mess with school start times.

The Atlanta Public Schools proposed extending elementary students’ day by 30 minutes this fall to address learning loss. But to make bus routes work, they would have needed to set an earlier start time for high school students.

That’s when the district ran into stiff opposition from parents and students. The district later backed off and added 15 minutes at both ends of the elementary schedule.

It’s challenging to find a balance between additional learning time and “just burning out kids,” said Lisa Bracken, chief financial officer for the district. “You can only bring them out so many extra days and add so many minutes to the day before you hit a tipping point.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)