A Wealthy Enclave Seeks Split from Atlanta, and Parents Take Sides Over their Schools’ Future

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated February 14

Georgia lawmakers have halted, at least for now, the Buckhead neighborhood’s effort to secede from the rest of Atlanta. On Friday, House Speaker David Ralston joined other Republicans in opposing legislation that would have allowed residents in the affluent community to vote on cityhood this fall.

Caren Solomon Bharwani has lived her entire life in Buckhead, an exclusive Atlanta enclave known for stately homes set back from dogwood-lined streets and upscale shopping on Peachtree Road.

Her kids have enjoyed Atlanta’s school offerings, including the popular International Baccalaureate program, and she’s formed tight bonds with educators providing services to her two children with disabilities.

That could be upended, however, if a vocal segment of Buckhead’s mostly white and wealthy population achieves its goal to secede from the city. Georgia law doesn’t allow the neighborhood to form its own school district. Secession, therefore, would leave 5,500 students and 800 employees in the neighborhood’s eight schools in limbo; unless legislation passes to keep them in the Atlanta Public Schools, they’d be subsumed by the surrounding Fulton County school system.

Bharwani said she “desperately” fears losing the support her children receive if the neighborhood secedes.

Proponents of a Buckhead breakaway — including many with school-age children — complain of rising crime, neglected potholes and an encroaching homeless population. But opponents view the effort as racially motivated and legally shaky. Buckhead, which is 86 percent white, generates an estimated $230 to $300 million in property taxes that is used to fund education. As with similar secession efforts across the country, the proposal has the potential to siphon off revenue from the region’s more affluent families, leaving residents in Atlanta’s majority Black district with fewer resources.

“Residential secession movements, typically driven by wealthier white communities, are almost always bad for education,” said Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a left-leaning think tank. If Buckhead is allowed to secede, “concentrations of poverty will increase in Atlanta, making students left behind worse off. The tax base necessary to support Atlanta public schools will suffer.”

The move comes as the district continues to grapple with persistent inequities. A 2019 report from the Latino Association for Parents of Public Schools estimated it would take more than a century for Black students to catch up with their white peers in reading and math.

The issue has divided neighbors and policymakers, and presented newly elected Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens with one of the first major challenges of his tenure. It is already one of the most contentious issues before state lawmakers this year. At least two secession bills await action, and more could be introduced before the session ends.

‘Right to vote’

Bill White, a former Democrat-turned-Trump-fundraiser who chairs the Buckhead City Committee, insists he’s not trying to weaken the Atlanta district’s tax base.

He promises that final legislation will specify that students can remain in their schools and the Atlanta district will hold on to its share of the property tax revenue Buckhead generates. He advises Atlanta’s district leaders — who oppose secession — to stick to their mission.

“Instead of attempting to interfere with Buckhead’s 70,000 citizens’ absolute right to vote on its own destiny, we hope [Atlanta Public Schools] will focus all its attention, resources and capabilities on the singular and much more important goal of providing higher quality education for our beloved children,” he said in a statement.

But many are skeptical of White’s promises to ensure stability for neighborhood students.

Mikayla Arciaga, a former Atlanta Public Schools teacher who lives in Buckhead and ran unsuccessfully for the school board last year, accused proponents of “baffling overconfidence.”

“It might be sorted out,” she said, “but we’re talking about our kids, who have already experienced two years of education disruption.”

White and other proponents argue that becoming a city would allow them to take public safety and other services into their own hands. Once a rural getaway for Atlanta’s old-money families, Buckhead was annexed into Atlanta in 1952. But Buckhead, like the city as a whole, has faced a recent crime wave that has put residents on edge.

Police data released last summer showed rates of robberies, aggravated assaults and car thefts were higher in Buckhead than citywide. But Atlanta’s mayor recently announced plans to open a new neighborhood police precinct and in January, a new police captain for the area said the community was starting to see a decline in violent crime.

Some parents support secession despite the uncertainty over Buckhead’s schools. Meredith Bateman, who has two children at Atlanta Classical Academy, a charter school, is among them.

A Buckhead resident since 2002, Bateman said she no longer feels safe in her community and is careful about where she stops to get gas. In 2020, a man pointed a gun at her husband and daughter during a moment of road rage on a residential street. She doesn’t allow her daughter, now 15, to go to Lenox Square — the area’s high-end shopping mall — by herself.

“That’s not normal. She should be getting some independence,” Bateman said. “Gone are the days of saying, ‘I’ll drop you at the mall, and I’ll pick you up later.’”

‘Two years of education disruption’

Opponents of secession say there are too many unanswered questions. Among them: What will happen to the district’s buildings and employees if the students become part of the Fulton schools. Atlanta school board member Michelle Olympiadis said it’s possible Fulton would buy out or lease the buildings. Employees would be displaced and have to reapply for positions.

“What teachers are going to want to stay through that turmoil?” Arciaga asked.

But she agrees city services could improve. Some parks, she said, haven’t been maintained in years, leaving residents to pick up trash and remove broken tree limbs.

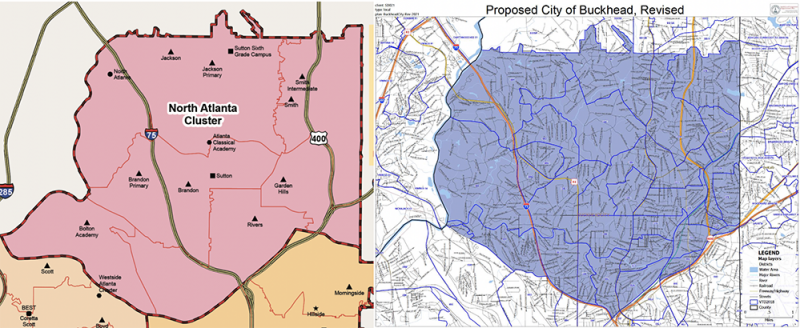

Another complication is that the proposed city limits drawn up by the Buckhead City Committee don’t match current school attendance zones: Left out are the more diverse neighborhoods on the edges.

“Magically, the areas they’ve not included tend to be the higher minority areas,” said Keisha Burgess Prentiss, who has a fifth grader at Bolton Academy and a younger child entering pre-K this fall.

She moved to the area specifically to enroll her children in the district’s International Baccalaureate and dual language Spanish immersion programs. But the elementary school her older daughter attends is outside the proposed boundaries, while the middle and high school lie within. If Buckhead becomes a city and the schools join the Fulton district, her children would no longer be eligible to attend.

Leila Laniado, a proponent of secession, is confident her daughter will be able to remain in the Atlanta district. As a Hispanic woman, she rejects the notion that residents want to keep out minorities.

“Every time people bring race into the discussion, it’s done purposely to divide,” she said.

Fulton officials, meanwhile, have mostly stayed quiet as their legal team weighs potential scenarios. One possibility is that the two districts reach an agreement in which students living in Buckhead remain in the Atlanta district, said spokesman Brian Noyes.

But he added that officials have avoided the debate and don’t want to “spend a lot of energy around what-ifs.”

Not the first attempt

For now, supporters and opponents are fixing their attention on the state legislature. Four Republican lawmakers from outside Buckhead introduced bills in support of secession, but that doesn’t mean state GOP leaders are unified on the issue. Former U.S. Sen. David Perdue, who is challenging Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp in the May primary, is in favor of a referendum on cityhood, while Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan is opposed. House Speaker David Ralston hasn’t taken a stand.

In a move some predicted would kill the effort, Duncan assigned one of the bills related to secession to an all-Democratic committee. There hasn’t been any action on the issue since mid-January, but those on either side expect they won’t know the outcome until the session ends March 31.

Duncan argues that rising crime is not unique to Buckhead and stems from racial unrest and the pandemic. Secession, he says, won’t solve the problem and would leave Atlanta with fewer financial resources to prevent crime.

“Criminals will still find their way to Buckhead despite the change in mailing address,” he wrote in an op-ed.

There have been past secession movements in Buckhead, but they didn’t reach the legislature. A 2008 newsletter arguing in favor of a breakaway lamented that the community’s taxpayers were “simply tired of having our votes and money taken for granted by the City of Atlanta.”

Olympiadis, the Atlanta school board member, thinks the current effort has more momentum. If cityhood proponents are successful, she fears, other wealthy parts of the city, such as Midtown, will follow suit.

If the issue gets through the legislature and wins at the polls, Bharwani, an organizer of opposition group Neighbors for United Atlanta, expects the matter to wind up in court, with families hanging in the balance until it’s settled. The cityhood committee can “write in their bill that [Atlanta Public Schools] has to continue educating the kids,” she said, “but there’s no provision in Georgia law that allows for any of this to happen.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)