Left Behind: Can East Baton Rouge Schools Survive the Breakaway of a Wealthy — Majority White — Community?

Corrections appended July 16

Located on Baton Rouge’s fast-growing south side, Long Farm Village is a mashup of Antebellum and subdivision. At the entrance to the development, a fountain dances. Just beyond, 18-foot columns frame wide porches. Garrets punctuate soaring roofs. The neighbors are much, much closer than on an actual plantation, but so is Starbucks. And the houses, with prices hovering between $500,000 and $700,000, come with amenities like jetted tubs and quartzite countertops.

Across the street sits Woodlawn High School, which bears the curious distinction of being one of only two high schools in East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools that has neither strict entrance requirements nor a failing grade on state report cards. Getting into the either of the city’s A-rated high schools, both magnets, takes a minimum of four consecutive terms of passing grades and mastery on state exams.

For the two-thirds of district students who lack that academic résumé — and who can’t vault other hurdles, such as hand-delivering paperwork during business hours, demonstrating early exposure to Montessori instruction or acing an interview — Woodlawn is the only option that’s not a D or F school.

Woodlawn’s middling C obscures a wide gap in academic outcomes among its 1,200 students, who are tracked into vastly different classrooms. Ten years ago, as the unincorporated area around the school was swelling with developments like Long Farm Village, district leaders positioned Woodlawn to compete with parochial schools, which in Baton Rouge draw one of the highest share of residents in the country.

The district opened several gifted and talented tracks, all with attractive curricular offerings and high entrance requirements. One of the programs boasts average class sizes of 10. Others require a writing sample or audition. The Great Scholars Program asks for an IQ test. Applicants living outside Woodlawn’s attendance zone must cite a “justifiable reason” for wanting to go — and supply their own transportation.

But the intentional schools-within-a-school strategy — which 8 percent of Woodlawn students have access to — wasn’t enough. Now, Long Farm Village and nearby neighborhoods are looking to secede from East Baton Rouge and form a new city, St. George, taking Woodlawn and four other schools — two rated B, one a C and one a D — with them. If the new municipality passes a vote in October, its residents will then petition the Louisiana Legislature to carve out a new school district. Woodlawn would be its crown jewel.

“Our vision,” the pro-breakaway website StGeorgeLouisiana.com explains, “is to be the state’s leading school system.”

Achievement gap, meet opportunity divide

With 86,000 residents, St. George would be the fifth-wealthiest city in the state — leaving behind a community where the median household income would be less than $37,000 — and the fourth secession from East Baton Rouge Parish Schools in the past 16 years.

Assuming a new school district has the same boundaries as the new city, it would take an estimated $85 million in state and local tax revenue and 12 percent of the current district’s student body. Estimates vary, but one civic group put the cost to the old district at $765 for every pupil left behind. The new city would be more than 70 percent white and less than 15 percent black.

Up to 6,000 children could be forced to change schools. What would happen to the approximately 446 Woodlawn students — likely the majority of the school’s 690 black students — who live outside the proposed new municipal boundaries remains unknown.

Indeed, St. George’s departure would compound the impact of decades of white flight that have left the district, the state’s second-largest, hypersegregated and almost entirely poor. Of the district’s 42,000 students, 90 percent are children of color and 84 percent live in poverty.

But even as white families have abandoned the district, white Republicans have retained control of the school board. One, 18-year veteran Jill Dyason, ran for and won re-election last fall despite having signed the petition to put the St. George secession on the ballot. Another was re-elected despite facing battery charges after being caught on video assaulting a teenager.

‘Your seat is not safe’

Against this backdrop, last fall saw the improbable election of two young black men to the school board. Both grew up in the struggling neighborhoods they now represent and attended the same impoverished but beloved middle school. Both earned law degrees from the same historically black university but chose to work in education.

Tramelle Howard is 29. Dadrius Lanus is 31. Neither has much use for what Howard describes as the city’s “wait your turn” culture, where running against an incumbent and without a nod from an older politician is a rarity. They campaigned wearing T-shirts that warned, “Your seat is not safe.”

Their election set off a shock wave. In the months since their January inauguration, community members have packed school board meetings, demanding change after decades of de facto, if not de jure, segregation and profound funding inequities. After a protracted power struggle, Howard was recently elected to replace Dyason as board vice president. This gives the new members a say in the agenda, something blacks on the board have historically been denied.

“Representation matters,” said Howard. “Just by being on the board, things look different. It’s not business as usual.”

The two join a relatively new board president, Michael Gaudet, who is a longtime board member of Teach for America South Louisiana and the founder of a successful charter school. Howard and Lanus’s arrival, he said, gives the board new potential.

The stakes are high. In coming months, the board will search for a new superintendent, a process that will shape how the district moves forward — with or without St. George. Just one-third of parish students currently have access to an A or a B school. A once-sleepy charter school sector has increased in size and quality, creating additional pressure for the 42 D and F schools that would remain in the East Baton Rouge district. And the district is still working to address an estimated $75 million to $100 million in damage from record floods that swamped buses, administrative facilities and 17 schools in 2016. Six of the schools required major renovation.

Whether or not the secession takes place — and it’s by no means a guarantee — the task is the same, said Gaudet. “I’m concentrating on what we have and building up the traditional schools,” he said. “I look at it as we are trying to make 25 years of change in five years. In a public system, that’s not the easiest thing to do.”

Because parents in the St. George area want the same thing as families in the neighborhoods where Howard and Lanus grew up, Gaudet said — access to a good school for their child — he believes the goal should be to bring the district’s overall level of quality up. “To a person, everyone is trying to do what they think is best,” he said. “The disagreement is on how to go about achieving that.”

Yolanda Braxton was one of several volunteer parents who interviewed school board candidates last summer as part of the endorsement process for the education advocacy group Stand for Children. She followed Lanus and Howard first on Instagram and then on Facebook, popping up at community events to see whether they were there — her personal litmus test.

Stand ultimately endorsed Howard and Lanus. Braxton admires both men. “I respect the boldness,” she said. “They’re asking questions no one will ask and no one will confront.”

Time, said Howard, has run out. “Schools in north Baton Rouge for 100 years have been getting less,” he said. “I firmly believe the St. George movement is rooted in racism. Look at the boundaries. You go down Florida Boulevard” — the east-west thoroughfare that bisects the city — “and it’s like the Mason-Dixon line. South of Florida, it’s white; north, it’s black.”

Backers of the secession effort did not respond to requests from The 74 for comment. Their campaign website provides an overview of the plan to follow the creation of a new city with a drive for a new school district.

A crumbling school and a galvanized community

Five miles north of Woodlawn sits Howard and Lanus’s alma mater, Istrouma, which offers both a middle school and a high school. The name means “red stick” in a local indigenous language, a reference to the red tree, or baton rouge, that French colonists used to mark the site of the city.

Opened in 1917, Istrouma has been buffeted by virtually every chapter of the district’s history. In 1963, it was the first parish high school to be integrated by court order. Current principal Reginald Douglas’s mother was one of 12 black girls chosen to attend the all-white school, which then had 1,700 students.

By the time the girls were escorted inside, the Justice Department had been in court, demanding that the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board comply with Brown v. Board of Education, for seven years. The case would last for another 40.

After the first 25 years of board resistance, the judge overseeing the case created his own integration plan and ordered the district to implement it. From 1981 to 1996, according to Tulane University’s Cowen Institute for Public Education Initiatives, students were reassigned and schools were closed — including temporary facilities set up for white students seeking to avoid “black” schools. White flight ensued, with 1 in 5 families enrolling their children in private schools — the fourth-highest rate in the nation.

In 1996, the school board pressed to end the most contentious part of the desegregation plan: busing. Instead, like many districts, East Baton Rouge proposed using magnet schools to attract students to integrated buildings. The court agreed but imposed conditions to try to ensure that the district would invest in neglected facilities and provide equitable access to schools.

Among other things, magnets could not duplicate programming. This was to avoid enabling wealthy families to segregate by setting up a second selective-admissions school with high-demand specialties — biomedical sciences, say, or engineering — and withdrawing to it.

In 2001, the judge who had overseen the case for 22 years quit in frustration, citing continued board resistance. Two years later, his successor closed the suit.

The end of the court order that by its very nature had kept the district intact cleared the way for two communities to split from East Baton Rouge. Baker, largely black, is now the second-lowest-performing school district in the state. Zachary, largely white, is now the highest-performing.

In 2007, the Central community broke away, taking a sizable portion of the remaining white students. In accordance with Milliken v. Bradley, a 1974 Supreme Court decision, the new cities had no ongoing obligation to help integrate the old school system.

And then, in 2013, an unincorporated southeast corner of the parish, St. George, began campaigning to leave but failed to garner the votes to put a required amendment to the state constitution on the ballot. Lawmakers said residents would have a better chance if they first incorporated as a municipality.

District breakaways are becoming increasingly common. Since 2000, at least 128 U.S. communities have sought to leave their school districts, according to the think tank EdBuild. Seventy-three attempts were successful and 17 are ongoing. The pace of proposed secessions has accelerated in the past two years.

Most infamously, after Memphis voters in 2010 elected to merge the impoverished central city district with its wealthier countywide counterpart, residents of six suburbs persuaded the Tennessee legislature to eliminate a ban on new districts — and then left to form their own.

At the start of all four Baton Rouge-area breakaway movements, backers complained that they lacked high-quality public school options, notwithstanding the resources the district was already pumping into magnet schools. In response, once freed from the integration decree’s equity provisions, the district sought to further bolster magnet schools in the most vocal communities.

Overall, 30 percent of district students in grades 3-8 passed state reading, math and social studies tests last year — but twice as many students in the 24 magnet schools passed than students in neighborhood schools. Reinforcing that divide, children who start in one of the selective magnet schools receive preference for magnet middle and high schools, leaving few seats for students who don’t start out in one of the advantaged programs.

As a result of this redirection of resources — and nearly 50 years of white flight — Istrouma became almost entirely black. Academic achievement plummeted and enrollment fell as poverty in the surrounding neighborhoods intensified. In 2012, the state took over Istrouma and subsequently closed it.

Alumni campaigned to have the school reopened, a process that galvanized the neighborhood.

“There were a lot of people in the community who wanted the school reopened who had no clout,” explained Douglas. “But a lot of alumni with clout took an interest.” Many older white Istrouma graduates joined the effort. In 2015, the state returned the school to the district, just in time for devastating flooding the following year.

Community uprising notwithstanding, it was clear from the start that Istrouma was not going to get the same kind of attention as schools in other, more affluent, neighborhoods. For example, as a failing traditional high school, Robert E. Lee, was being reborn as Lee Magnet High School on a brand-new $56 million campus next door to the proposed St. George district, Istrouma — which needed $10 million to $15 million in repairs alone — got $24 million in scaled-back renovations. Lee, now one of the district’s two A-rated high schools, moved into its new campus in 2016 with a cutting-edge biomedical program (a duplication of programming that would not be allowed under the desegregation order). Istrouma reopened in August 2017 as both a middle school and a career-focused magnet high school with a total of 500 students, less than a third its former size.

“I firmly believe the St. George movement is rooted in racism. Look at the boundaries.”

—Tramelle Howard

With only 11 percent of high school students and 26 percent of middle schoolers passing state tests, Istrouma earned a D on Louisiana’s most recent report card and carries an “urgent intervention needed” designation. Ninety-seven percent of students are black and 96 percent are impoverished.

On nearby streets, it looks as if the flood happened yesterday. Pavement is crumbled and lots are overgrown with weeds. Squat and narrow, many houses still bear the spray-painted Xs rescuers used to tag homes that had been searched for survivors. Few have been boarded up, much less rehabbed.

Braxton lived in one. A proud Istrouma graduate and the mother of two more, she also has a 16-year-old son with cerebral palsy who attends the school. She was home with the boy and a dead phone the day of the flood, despairing as she watched the water rise above his wheelchair. Two teenagers from next door came to the rescue just in time.

“I couldn’t carry him,” she said. “I couldn’t even walk through the water.”

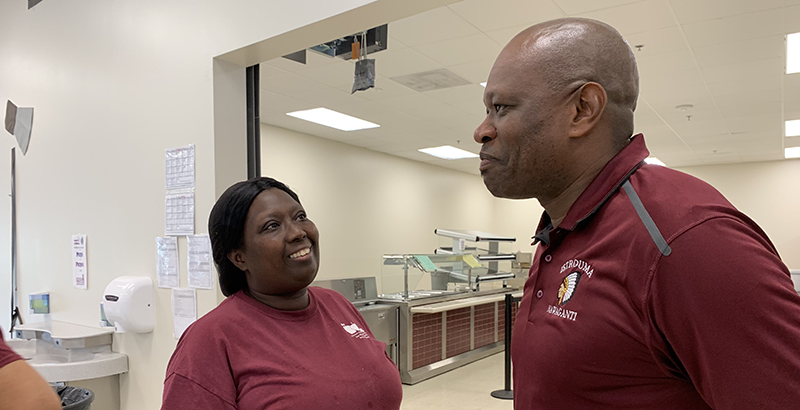

Since Istrouma reopened, she’s worked in the cafeteria, where, in addition to keeping order during lunch, she serves as an informal monitor of the school’s culture.

“I talk to every kid, every day,” she said. “The kids, they actually relate. If somebody wants to know something, they come to me, because I hear it all.”

She traces a notable increase in problem behavior in schools and violence on the streets to the summer of 2016, when weeks of community protests were followed by catastrophic flooding. On July 5, Alton Sterling was killed about a mile from Istrouma by two police officers. Two weeks later, three police officers were killed and three wounded in an ambush.

A few days after that, East Baton Rouge schools had just started a new year when a massive storm dumped three times as much rain on Louisiana as Hurricane Katrina. The district closed because of the weather Aug. 12 and didn’t reopen for 25 days.

Istrouma was spared because it sits on high ground, but other district schools were too damaged to reopen. Programs were consolidated in intact buildings, but with an estimated 4,000 teachers displaced — half of them employed in East Baton Rouge — district officials had to scramble to staff them. Adding to the disruption, buses were destroyed even as thousands of newly homeless students needed transportation from temporary shelters to school.

Board president Gaudet credits the current superintendent, Warren Drake, with helping the schools recover from the flood. But he cautioned that the rental housing on the city’s north side isn’t being restored, which has prevented students from returning to the neighborhoods surrounding some of the most challenged schools.

“Enrollment needs to shift more to the southern part of the parish, because that’s where housing will be developed,” he said. “We’re having to make $30 million in cuts this year. Maybe we just can’t run schools with 50 percent enrollment.”

A new board power play

After law school, Howard joined Teach for America, which placed him in a Baton Rouge school where he taught eighth-grade history. The first year went fine, but during the second, the other history teacher was fired, leaving Howard to serve 140 students. Compounding his struggles, as one of very few African-American teachers, he was called on to address a continual stream of behavior issues.

“I literally couldn’t physically return to the school after the first semester,” he recalled. “It was a good decision because it paved the way for the things I fight for now.”

Howard is now the impact manager at City Year Baton Rouge, a nonprofit that places AmeriCorps members in district schools to provide everything from attendance monitoring to academic tutoring.

Lanus is an education consultant and former dean of culture at Cristo Rey Baton Rouge Franciscan High School. He got a bachelor’s degree in education and taught his way through law school, then turned right back around after earning his Juris Doctor and started a master’s degree in educational leadership.

No sooner had the two been sworn in in January than it was discovered that board veteran Dyason had signed the petition to put the St. George breakaway on the ballot. Much of her school board district falls within the area that would become the new city.

Dyason defended her signature, saying she thought it was time to settle the secession debate. “I definitely don’t feel that it is a school board issue in any way,” she told the Advocate.

The revelation surfaced as Dyason was vying with Lanus to be elected board vice president. Officers typically have more influence on school board actions than their peers, but their influence on the East Baton Rouge Parish School Board has been outsize.

Historically, the president, vice president and superintendent determine the agenda, presenting the rest of the board with relevant documents at meetings. The result is that members are asked to vote on major issues they’ve not had time to fully consider.

It took 10 deadlocked votes, but in the end a compromise was brokered handing the vice presidency to Howard. Gaudet has vowed to share information with board members much earlier in the process, and Howard and Lanus said they plan to make sure it’s communicated to the newly energized residents who have packed recent board meetings.

“I’m concentrating on what we have and building up the traditional schools. I look at it as we are trying to make 25 years of change in five years. In a public system, that’s not the easiest thing to do.”

—Michael Gaudet

The St. George breakaway campaign, Lanus said, has galvanized many in the neighborhoods that will be left behind. “The community is very engaged now,” he said. “Every board meeting since we’ve been elected has had more than 100 community members present. That never happened before.” The goal now is to keep them focused as they discuss the district’s future.

The secession vote is set for Oct. 12, with only residents of the proposed breakaway area allowed to participate. The outcome is far from certain; Louisiana makes school district secessions harder than most states, and there is no shortage of opposition among the parish’s business and civic leaders.

Campaigns for and against the breakaway have marshaled differing analyses of its possible financial impact. At a minimum, St. George’s creation would mean a loss of 8 percent of the East Baton Rouge district’s budget — already running a $26 million deficit. Compounding the pain: Not only would the old district lose gleaming new facilities, it would still have to pay for things like teacher pensions and retiree health care in the new district.

The Baton Rouge Area Chamber, for one, has estimated that a breakaway would drain $53 million from Baton Rouge city’s coffers — yet leave the new city of St. George with a $9 million deficit. And even as supporters countered that St. George would start with a budget surplus of $10 million to $15 million, businesses and the owners of large properties within the proposed new city limits, including two hospitals and a mall, asked to be annexed into the city of Baton Rouge.

With Drake set to retire in June 2020, whatever the outcome of the October vote, the aftermath is likely to be his successor’s most urgent and controversial task. If St. George creates a school district, the East Baton Rouge board will need to redistrict, and the superintendent and remaining board members will have to decide how to move forward.

In addition to the financial losses, the smaller, poorer district would have to figure out how to pay for benefits for retired school system employees who worked in schools it no longer controls. Officials would also need to address the crumbling infrastructure left behind. And, Gaudet said, there are urgent issues of creating high standards for teachers and principals in neighborhood schools, as well as a system for monitoring progress in underperforming schools. Having weathered recent controversies, he believes, the once-complacent board may be emboldened to begin taking up these difficult matters.

Whether St. George withdraws or not, the question of inequities within the district will remain. A new superintendent will need to sell a plan for addressing the inequality to a board that historically has favored spending more on its elite schools than on its needy ones.

“I think our board has been very tone-deaf to that need,” said Howard. “They don’t like the fact that we are transparent and the community has rallied around us.”

Gaudet agreed that it’s a crucial juncture. The next superintendent must be able to communicate a vision to a populace that has just begun to engage. “This next superintendent selection is probably the biggest thing that will happen on the board in the next five years,” he said. “We definitely need this to be a visionary person.”

Rumors are already swirling in education circles about this or that out-of-town candidate supposedly visiting at the behest of different groups. The chamber has raised the possibility of studying communities such as Indianapolis and Camden, New Jersey, that have had some success raising achievement amid similar challenges.

Lanus, for one, has drawn up a wish list of traits he’d like to see in a new superintendent. Not surprisingly, he’s not interested in continuing the status quo.

“I’d love to see someone who is a nontraditional leader, who hasn’t been inside a system for several years,” he said. “I want somebody who understands what equity is and how to achieve it.”

The work, he reiterated, is the same whether St. George stays or goes. “The best thing we can do is make our schools good enough they don’t see the need for a separate school system.”

Correction: Stand for Children Louisiana endorsed both Tramelle Howard and Dadrius Lanus. Lanus is an education consultant and former dean of culture at Cristo Rey Baton Rouge Franciscan High School.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)