A Glimmer of Hope in Pandemic for Nation’s Ailing Catholic Schools, But Long-Term Worries Persist

Updated, Dec. 18

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

Last spring, after her 6-year-old son’s New York City charter school shuttered its doors in response to the pandemic, Sashaly Gomez would sit with her kindergartener, Landon, through each school day to keep him on task.

“He just gets distracted with the Zoom,” said Gomez. “He’s in his house so he wants to get up, he wants to get a snack, to get a toy. He wants to show his classmates a toy.”

Gomez is an operations manager at Flight Club, a well-known New York City sneaker outlet which closed temporarily in the spring due to the coronavirus. That’s what allowed her to be with Landon during the school day.

“I was one of the lucky ones who got to work from home,” she explained.

But the arrangement was temporary for Gomez, who said she was already disenchanted by her son’s charter school for its lack of communication around Landon’s academic struggles, including the possibility that he could get held back a year. By the fall, Flight Club had reopened, meaning that Gomez would need to go into work. No one would be there to help her son with his Zoom classes.

“It was basically like I was in school with him, so I just knew going forward, either I would have to cut back from work or we would have to find a different alternative,” said Gomez. “We couldn’t do remote.”

Exploring other options, Gomez and her husband found Mt. Carmel-Holy Rosary School in upper Manhattan, where the school administration told them that, if at all possible given community contagion levels, in-person learning would be available in the fall. After securing a scholarship that helped with the $5,200-per-year tuition, the Gomez family enrolled their son.

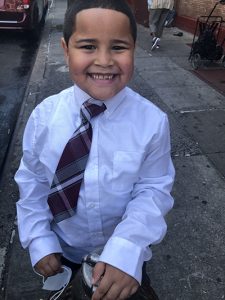

It’s been a great fit for Landon, reports Gomez. The in-person cohort in his first grade class is small, and he has made close friendships. After facing difficulties in his former school, Landon made secondary honor roll this fall at Mt. Carmel.

“He’s thriving,” said Gomez proudly, whose faith in her son’s new school remains strong even though it, too, had to pause in-person learning this week because of the coronavirus. The school had gone 14 consecutive weeks with its doors and classrooms open. Principal Molly Smith said that Mt. Carmel plans to resume in-person learning in mid-January after a two-week stretch of remote instruction to allow students and teachers to quarantine after any holiday travel.

As the worsening COVID-19 pandemic keeps many school districts closed across the country this fall and winter, the Gomez family’s story has replicated itself in other households — breathing hope into a Catholic school sector that for decades has been bleeding students.

Though Catholic schools for centuries have played an outsized role in educating women and immigrants in this country, propelling many marginalized students and families to the middle class, their numbers have been on a steady decline for years. Since 2010, Catholic elementary school enrollment has dropped 24 percent in urban dioceses, and 19 percent in the rest of the U.S., according to national data.

This past September, however, multiple archdiocese reported surges of new students. In Boston, Catholic schools saw a nearly 15 percent bump in enrollment after the Boston teachers union called for a remote start to the school year.

“When it hit the evening news, our phone(s) started ringing off the hook all across all of our 100 schools,” Thomas Carroll, the superintendent of schools for the Boston Archdiocese, told WBUR in September. “I joke that we should send a thank you note to the school districts, because of their tone deafness, in terms of what the parents were looking for.”

The Archdiocese of New York, which takes in three New York City boroughs and seven counties north of the city, also saw a surge in student interest, receiving 1,800 applications this fall from students previously enrolled in public schools, T.J. McCormack, director of communications for New York Catholic schools, told The 74.

“Our web traffic went through the roof,” he said, with some schools’ websites going from almost no daily traffic to over 40,000 unique hits.

But while such examples indicate that there have been pockets of a post-pandemic enrollment boom for Catholic schools, the national picture does not look as hopeful, according to Dale McDonald, director of public policy at the National Catholic Educational Association. Even as some locales pick up new students, overall this school year there has already been a 6 percent enrollment drop for Catholic schools nationally, she said. Before it was clear that many of their public school neighbors would not reopen to in-person learning — or would do so sporadically — the financial impact of the coronavirus forced the Archdiocese of New York to close 20 of its schools this summer, a combination of weak fall registration and less parish support.

Catholic schools are typically the least expensive private school option available to parents, thanks to those parish subsidies. This year, however, few churches are holding in-person Masses, McDonald explained, which means no basket being passed to collect Sunday contributions and less revenues taken in by the church. Some Catholic schools have had to cut back on scholarships.

“There’s less tuition assistance available,” said McDonald. “For many families who were counting on a couple of thousand dollars (in) aid, only getting maybe a thousand makes it impossible for them to continue.”

For months, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos fought to reroute up to a billion dollars in funding from the CARES Act, passed in March, to K-12 private schools, including religious schools. In September, however, DeVos backed down after three federal judges ruled that she lacked the authority to divert resources intended for low-income students in public schools. Lacking significant federal aid, many parochial schools are now facing an existential crisis.

Adding to their financial woes, social distancing guidelines have forced some schools to limit their class sizes — regardless of surges in student interest.

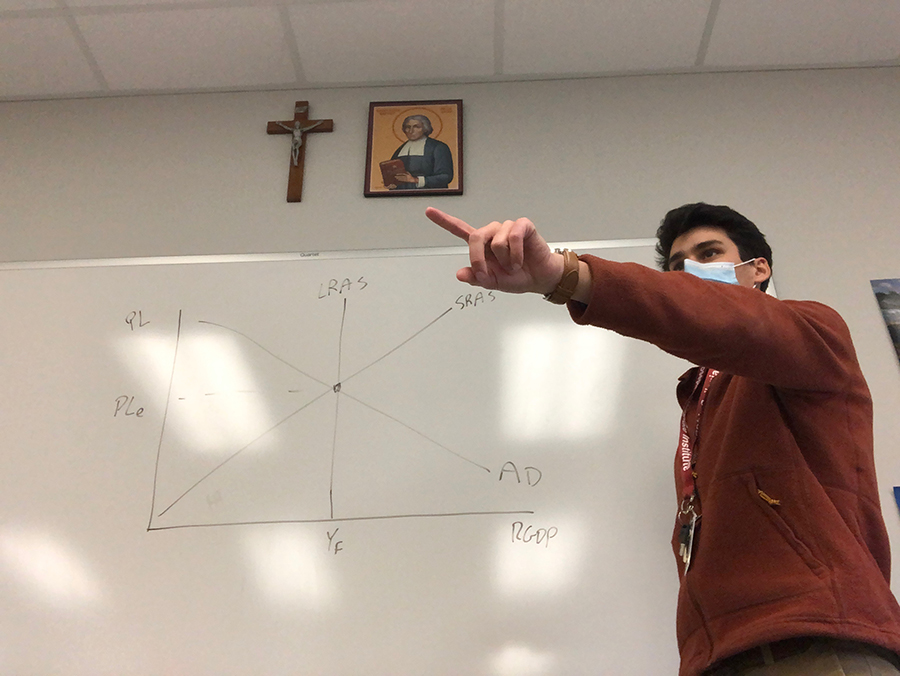

St. Joseph’s Collegiate Institute, an all-boys Catholic high school in Buffalo, New York, had to cap their freshman class this fall at 160 students, similar to their numbers in years past, despite many families still seeking spots, said first-year St. Joseph’s teacher Will LaCroix.

“There’s literally not enough room in the school to have more kids,” said LaCroix, who worked with a team of fellow teachers over the summer to map out safe desk spacing in classrooms and demarcate social distancing protocols with tape on the floor.

St. Joseph’s has a shadowing program for incoming 8th-graders considering the school, and already, tours are booked through May. At a recent open house for prospective families, parents’ number one concern was that the school was committed to safe in-person learning, said LaCroix.

“The biggest thing that I was hearing from parents was the fact that we were open. And a lot of these parents were really upset that their kids’ public schools were not open.”

The Buffalo Catholic school did have to go remote for two brief stints, once due to spread of the virus, and once because of changing state regulations, which mandated virtual learning due to COVID-19 levels in the surrounding community.

Thanks to distancing protocols and mask-wearing rules, LaCroix feels safe at St. Joseph’s, but he also knows that maintaining in-person learning is a major part of his school’s appeal at the current moment.

“It’s such pressure to stay open because it’s like why would you pay to online learn when you could do that at public school?” said LaCroix.

Michael Hartney, assistant professor of political science at Boston College, co-authored a paper analyzing the effects of public school exit to Catholic schools since the pandemic. He found evidence that public schools were sensitive to that threat and that “districts located in counties with a larger number of Catholic schools were less likely to shut down and more likely to return in-person learning.”

On the other side of that equation, Catholic schools are aware of where their competitive edge lies and how essential in-person learning is to their survival.

“In contrast to the public schools, they need the revenue. They have to have the revenue or they’re gonna close,” Hartney said. “Fewer parents are going to be willing to pay… to have sporadic Zoom teaching.”

When public school districts do eventually reopen, it will mean Catholic schools that have been able to maintain in-person learning will lose their advantage, Hartney predicts. Even for schools that have seen pandemic-induced enrollment boosts, that doesn’t bode well for retention of families in the long run.

“Ultimately, an economist would say, at the end of the day, a year from now, two years from now, costs are costs,” said Hartney. “People will look at their budgets and say ‘Do we really need to be spending an extra $9,000 or $10,000?’”

Indeed, Kathleen Porter-Magee, superintendent of Partnership Schools, the network of urban Catholic schools to which Mt. Carmel belongs, sees the direct impact that finances can have on enrollment. In New York, enrollment at Partnership Schools has stayed almost steady this school year, with a modest 4 percent overall drop. In Cleveland, however, the other city where the network operates and where state and citywide voucher programs allow many disadvantaged families to attend their schools free of charge, enrollment has surged 39 percent at Partnership Schools since the pandemic, said Porter-Magee.

“It’s a tale of two cities,” the network superintendent said.

Voucher programs like Cleveland’s are rare, however, and McDonald, of the National Catholic Educational Association, shares Hartney’s fear that the pandemic may ultimately hurt parochial schools. Even while citing national drops in Catholic school enrollment since the pandemic, McDonald worries that as the economic fallout of the coronavirus continues for many families, the worst is still to come.

“The kids that we took in because the public schools were closed, what impact will the reopening of public schools have on that?” she wonders.

However, for the Gomez family, the decision doesn’t come down to finances. Landon’s father, who had been the family’s primary breadwinner lost his job as a restaurant manager in June due to the pandemic. But despite money being tight, the Gomezes say there’s no price tag they could put on seeing their son learn and grow.

“If a charter school was free, and me paying for a Catholic school, for me, it’s worth it,” Sashaly Gomez said.

While the fate of Catholic schools remains subject to the ongoing impacts of the coronavirus, Landon is staying put — and his younger brother, 3-year-old Nolan, may even be joining him.

“He’ll continue at Mt. Carmel,” Sashaly Gomez said. “Post-pandemic I would love to add my other son to the school because it’s easier to have two kids at the same school than putting them in separate schools.”

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

Correction: Enrollment at Catholic Partnership Schools in Cleveland has grown 39 percent since the pandemic. An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the percentage based on information provided by the Partnership.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)