COVID Poses an ‘Existential Threat’ to Many Private Schools, but Congress Might Block DeVos’s Push for Relief

With the pandemic still raging and the economy in shambles, public schools are closing the academic year in financial freefall. Now a conflict between states and the federal government will determine just how much of their budgets they must share with private schools.

In a pointed letter last month to the Council of Chief State School Officers, a national organization for state superintendents, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced that she would compel public school districts to hand over a percentage of the emergency relief aid granted through the $2 trillion CARES Act. The proposed rule, which many believe is a distortion of the Act’s intent, would imbue with the force of law a recommendation that DeVos first issued in late April.

The idea itself was bold, the language DeVos chose almost provocative. Arguing that private schools were “overwhelmed” by the fiscal impact of long-term closures, the secretary accused local and state authorities of wanting to “share as little as possible with students and teachers outside of their control.” A draft of the rule would be ready for public comment shortly, she added, with a final version in effect by the beginning of the 2020-21 academic year.

Until then, DeVos’s policy is merely guidance, which states may or may not adhere to. In fact, administrators in Maine, Indiana and Mississippi have already said they will ignore it. Congress, which has waged brutal fights against the department before, could also nix the proposal. Even before DeVos sent her letter to the state chiefs, retiring Sen. Lamar Alexander, perhaps the GOP’s most authoritative voice on education concerns, said that he disagreed with her interpretation.

Whether or not she prevails, there is no doubt of one thing: A huge number of private schools are, as DeVos claims, overwhelmed by the challenge of adapting to the post-COVID world. The private sector is, if anything, more variegated than the public system, with cash-strapped religious schools co-existing alongside elite academies with billion-dollar endowments. Already, several dozen private schools educating more than 6,000 children have permanently closed, according to a tally kept by the libertarian Cato Institute; in the absence of more federal assistance, their defenders warn, the deluge will continue.

DeVos’s critics say that the department’s posture on emergency relief is just another facet of her campaign to privatize education. With her support, the Trump White House has backed legislation to subsidize private school tuition in the U.S. tax code, even as its proposed 2021 budget proposal included major cuts to federal programs benefiting public schools. The administration is also backing a lawsuit that could undo state-level bans on public funding for religious education. A ruling on that case, heard by the Supreme Court in January, is expected sometime this month.

“Without a doubt, she’s clear that she favors private schools over public schools,” said Jack Jennings, an education policy veteran who served as a Democratic congressional aide for three decades and founded the Washington-based Center on Education Policy. “There’s no limit to her criticism of public schools, and there’s no limit to her praise of private schools. She clearly wants to shift the platform to private schools.”

For Kathleen Porter-Magee, it’s less a question of motivation than one of survival. As superintendent of the Partnership Schools, a network of Catholic schools in New York City, she’s deeply worried about the future of the sector, which has historically served many poor families with few other options. Now, she said, private institutions that can’t count on some form of public assistance — either in the form of vouchers or tax credits, which are provided in some states — are venturing into dangerous waters.

“Private schools in non-choice states are not guaranteed revenue at all,” she said. “If families can’t pay tuition, and they don’t have public funding in the form of tax credits or vouchers, and they don’t get any CARES support, we’re dooming them and leaving the kids adrift.”

Equitable services

The coronavirus outbreak and resultant school closures are enormously destabilizing events on their own, but they are also occurring at a time when the private education sector is undergoing a significant and painful transition.

A team of researchers, including Stanford professor Sean Reardon and Harvard University economist Richard Murnane, released findings in 2018 showing that the portion of American students attending private schools was segregating by income. Even as the wealthy continued to enroll their children at the highest rates, their middle-class counterparts were swiftly pulling away from the sector, led by millions of families abandoning Catholic education.

That hollowing-out leaves the once-coveted academies, and particularly urban Catholic schools, in a precarious position when the economy goes cold, Murnane observed.

“It’s tied up with how this COVID crisis is going to affect jobs,” he said. “One of the things we saw with the Great Recession was that, even for relatively affluent families, the percentage who sent their kids to private school declined for two or three years. If you think you’ve got a tight budget, that’s a discretionary expenditure.”

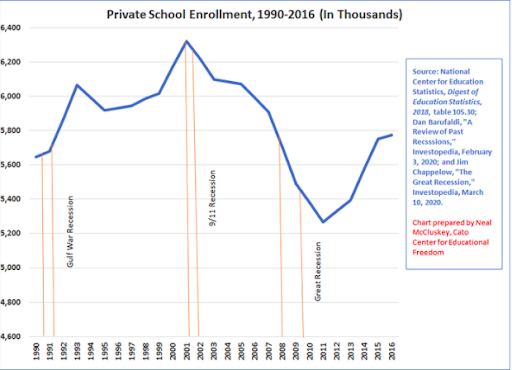

That claim was echoed by Neal McCluskey, head of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom. In a blog post from April, McCluskey argued that thousands of private schools were facing an “existential threat” from the economic downturn. In the decade between 2001 and 2011, private school enrollment shrank by more than 1 million students and roughly 5,000 schools closed.

McCluskey said that many private schools wouldn’t be able to survive an environment in which the federal government props up public districts but doesn’t offer them any help. A skeptic of state intervention, he said there were persuasive arguments against further rounds of COVID recovery funding. But assuming that some aid to schools is eventually passed, it “shouldn’t discriminate for or against any particular subset of students.”

“It’s supposed to be relief for the entire country, since the entire country is impacted by COVID-19,” McCluskey said. “The private schools, which have always had to compete against something free, are all drowning, but the only ones getting life preservers are public schools. So you’re essentially killing the private schools.”

Some well-funded private schools have received criticism for accessing funds directed to small businesses through the government’s Payroll Protection Program. Thousands of religious institutions have done the same, allowing them to continue paying employees even as they postpone church services and collect fewer contributions from congregants. That initial wave of support crested weeks ago, and as Congress debates next steps, dozens of schools around the country have shuttered forever.

The dilemma galvanized Secretary DeVos to issue her original guidance on sharing COVID relief. But almost immediately, state officials asked her to reconsider the move. In a letter from May 5, the CCSSO claimed that DeVos had misinterpreted the language of the CARES Act, which stipulates that its emergency education fund should be disbursed in the same way as funding from Title I, the U.S. government’s provision benefiting low-income students.

Historically, some Title I dollars are allocated to provide “equitable services” to eligible students in private schools. But DeVos’s guidance encouraged states to share with private schools regardless of how many poor families they serve. Such a regulation “could significantly harm the vulnerable students who were intended to benefit the most from the critical federal COVID-19 education relief funds,” the group wrote.

A few weeks later, Sen. Alexander made news by essentially agreeing with the state chiefs, saying that when Congress passed the CARES Act, most of its members assumed its education funds “would be distributed in the same way that Title I is distributed.” DeVos’s tart response to the CCSSO followed the next day.

Jennings said that DeVos’s proposed rule, which would force states to follow the department’s guidance, faces long odds of ever being adopted. With multiple superintendents — including some from deep-red states — chafing at the idea of handing over precious funds to schools that may serve only wealthy students, Congress could easily use its spending powers to kill the idea.

“That’s been the history of these things when you have somebody like Alexander opposing it,” he said. “He’s a strong voice when it comes to appropriations for education, and he’ll just go to the Appropriations Committee and say that the secretary can’t use any of these funds for a rule such as she’s proposing. And she’ll be hamstrung, won’t be able to go ahead.”

Even while advocating that more resources be extended to private schools, and conceding that DeVos’s interpretation of the law was “not crazy,” McCluskey agreed that it was a stretch.

“In terms of what the CARES Act itself says, I think she’s probably misinterpreting the law. I think the CARES Act says that the money is supposed to be allocated based on low-income kids and those who may qualify for typical federal aid programs.”

An Education Department spokeswoman did not respond to a request for comment on when a draft of the rule could be expected or what might be included in it.

A slow decline

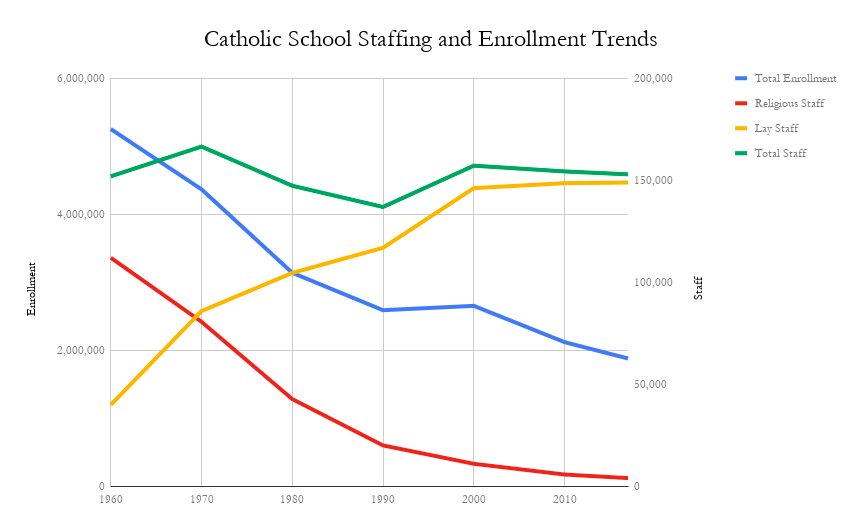

The nationwide decline in Catholic school enrollment has been underway for over half a century, according to the National Catholic Education Association. Decreasing from a peak of 5.2 million American students in the 1960s, the Catholic sector now encompasses just 1.7 million today. Just over the past decade, nearly 1,200 schools closed or consolidated, while only 244 were opened.

The downward trend is attributable to a few factors, including the shrinking supply of priests and nuns to serve in academic roles, the aftermath of the clergy abuse scandal and the broader secularization of life. But one of the central challenges facing Catholic education is a demographic and geographic shift in American schooling: Middle- and working-class families once lived in major urban centers and flocked to diocesan schools, which they perceived as superior to those operated by overtaxed districts. But over several decades, those families decamped to the suburbs, where they have grown satisfied with local public schools.

Those still seeking a Catholic alternative are more likely to embrace the Church’s specific values and pedagogy. But even while Catholic schools remain cheap compared with Phillips Academy or the Groton School, few parents can afford to pay tuition to a school their children aren’t able to step inside. Nicole Stelle Garnett, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, said that she had already heard from Catholic school parents who were considering a permanent switch to homeschooling.

“A lot of people with really modest incomes are able to scrape together tuition to send their kids to Catholic schools, because they’re relatively low-tuition schools,” she said. “And those parents are losing jobs. So if parents can’t afford tuition, and the school doesn’t open in the fall, it really starts to seem like the value proposition doesn’t make any sense.”

Garnett’s 2014 book, Lost Classroom, Lost Community, examined the impact of widespread Catholic school closures in Philadelphia and Chicago, finding that serious dysfunction followed in their wake. The schools, she wrote, provided more than academic services; they were “anchoring institutions” that brought communities together.

“These are stabilizing community institutions at a time when our communities desperately need stabilizing institutions,” she said. “We’re at a very challenging economic time, social time, and we need institutions that provide social capital, however they generate it. It’s a very sobering thought because the ones that are most likely to close quickly are probably in the neighborhoods that need them most.”

Porter-Magee also referred to the extra-scholastic support that Catholic schools provide for their surrounding communities. As an example, she pointed to one of her network’s teachers, who started an oral ESL course for Spanish-speaking parents after discovering that many were illiterate in their native language.

Without more help from the federal government, schools like those in the Partnership — which operate in low-income neighborhoods in Harlem and the Bronx — would face the prospect of extinction, she said.

“The American system of Catholic schools is the only private system that serves poor students and poor communities at scale, and the potential that this will almost wipe out that sector is real,” she said. “We can’t just look to the government to save us, no question, but … we need a lifeboat of support just like everybody else does.”

Jennings, who attended Catholic schools in Chicago and once considered a career in the priesthood, noted that Church leaders like New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan had spent years lobbying for public support but hadn’t succeeded in persuading politicians. That doesn’t bode well for their future, he concluded.

“The Catholic bishops did a wonderful thing that wasn’t in their interest — they sustained these schools for as long as they felt they could. But it seems as if those days are coming to an end.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)