74 Interview: Veteran Researcher Anthony Bryk on Chicago Schools’ ‘Radical’ New Direction

The author of a new chronicle of the Windy City’s reform era reflects on the challenges ahead for the nation’s fourth-largest school district

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

May 15 will mark the beginning of a new day for schools in Chicago.

That’s the day Brandon Johnson, a former organizer for the Chicago Teachers Union, will lay down the mantle of progressive insurgent and take the oath of office as mayor. Last month, in the city’s closest mayoral race in 40 years, Johnson prevailed by just 26,000 votes over former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas, a technocrat who ran on a record of support for education reform.

The win represented a generational breakthrough for Johnson and his union, which has waged a decade-long struggle against a regime of school choice and accountability that stretches back to Vallas’s tenure. That ambitious complex of policy and regulation was carefully installed over decades, including a lengthy interval during which Chicago saw some of the fastest academic growth of any major school district in the United States — but also a steadily building resistance from educators and community members over controversial policies like school closures.

The lessons of the long reform era are detailed in a new book, How a City Learned to Improve Its Schools, released in April by Harvard Education Press. In five chapters, the text chronicles the genesis of Chicago Public Schools’ transformation — beginning with a 1988 state law initiating an unprecedented decentralization of autonomy from the district office to local school communities — and the adoption of stringent accountability measures that in some ways anticipated the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

The book’s lead author, Anthony Bryk, offers a rare perspective on the city. A veteran researcher and former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bryk previously served as a professor of urban education at the University of Chicago. In 1990, he helped found the UChicago Consortium on School Research, a data hub that has generated a host of influential studies on America’s fourth-largest district.

Bryk believes the evolution of CPS under leaders like future U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan and long-serving Mayor Richard M. Daley helped spur a leap forward in student performance by engaging CPS families, improving the selection and development of teachers, and allowing administrators more latitude in running their schools. The results were revealed in a 2017 analysis by Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon, which found that Chicago elementary and middle schoolers gained six years of academic benefits from just five years in school.

But he has reservations about the future of the city’s schools, and particularly the gradual establishment of an elected board that will oversee them. In an interview with The 74’s Kevin Mahnken, Bryk offered his views on what worked during Chicago’s turnaround; the warning signs ahead, including dramatically falling enrollment numbers and mounting debt; and the union’s overnight move from one of the district’s biggest critics to perhaps its most important actor.

“This might be as radical a reform in governance as one could envision,” Bryk said.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Your book depicts a long journey toward school improvement in Chicago during the 1990s and 2000s. But the years since have been marked by a great deal of tumult, obviously including the pandemic. How far has the district come, and where is it headed?

Anthony Bryk: I think about Chicago Public Schools within the broader context of major American school systems at the moment. We are clearly in an unprecedented time with respect to post-pandemic trauma and learning loss, which have been especially pervasive for those students who are most dependent on strong civic institutions. Of course, we’re also living through a period of racial reckoning as we come to better understand the vestiges of systemic racism that operate in big urban school districts.

Then you bring in the Chicago-specific context of a new mayor and, perhaps even more important, the shift to a 21-person elected school board over the coming years. Most people don’t realize that Chicago has never had an elected board, and a 21-person board is just a huge change. Over the last number of years, there’s also been renewed conflict between labor and management in schools, and — like a number of other places, but maybe more so in Chicago — the district is experiencing a new round of budget shortfalls.

Together, these factors pose extraordinary challenges. Although the array is quite different, it appears to me in some ways like what Chicago felt like in the 1980s, at the beginning of the work to turn around local schools. [Then-Education Secretary] Bill Bennett visited Chicago and called it the worst public school system in America. I doubt if it was the absolute worst, but it was clearly one of the most troubled public school systems in the country. And while the specific challenges that had to be confronted were different at that time, their scope certainly strikes me as comparable to what the city is facing now.

“I would expect the teachers’ union to organize and have a significant voice within that new board. If you get this kind of progressive alignment — the union and the mayor and school board and the governor in Springfield — I’m curious to see whether these people can actually solve these challenges. It’s one thing to go around criticizing what others do, but they’ll now be in a position to do something.”

The big difference, as we write about in the book, is that there is now a civic architecture that grew up over the past several decades. It’s an interesting kind of architecture in that the politics of urban districts typically tend to focus on shaping what happens at the system’s center; but a lot of the energy in Chicago’s reform push was focused on making ideas work out in schools and finding new ways of developing teachers and school-based leadership. A lot of social learning emerged around the work of school improvement, and there was space for new ideas. The district, over the period of [Arne] Duncan, was open to partnerships with the business community, foundations and lots of new organizations. It generally kept things stabilized even through the period of 2010–2017, when we saw a lot of financial issues and churn in system leadership.

That’s what leads me to think that Chicago is still positioned well to take on these new problems. The improvement work in Chicago — keeping kids on-track through high school and onto college, developing a framework of essential supports and regularly reporting evidence — has created coherence among an incredibly diverse array of actors, and those will be resources in the years ahead. Having said all that, it’s really hard for me to discern how this shift to an elected board will unfold. In my mind, that’s the real wild card.

Can you be more specific about the steps that led to academic improvement over the last few decades?

We describe decentralization as the DNA of reform. Over the decades, there’s been a lot of attention paid to governance as a key lever for reform. What’s important to take from the Chicago story is what governance change did and the mechanisms it opened up. One of the things it did was to recognize schools as the principal unit for change: How do we get schools to get better at their core work?

The 1988 law [the Chicago School Reform Act, which formed local school committees that gained authority over hiring and budgetary practices in individual campuses] made that critical. It helped reform the relationships between and within schools and local communities, and it brought a horizontal dimension to relationships where, traditionally, educators looked vertically up to bureaucratic actors to tell them what to do. And by virtue of the fact that there were real resources made available to schools, there were opportunities for innovation to occur; a lot of them were wasted, but some very positive things emerged and eventually spread across the system.

One of the key initiatives was all the attention to how principals were selected, supported and evaluated. Again, when you see schools as the prime mover for change, you focus carefully on the quality of leadership at school sites. Chicago is a huge district, but there are only about 600 people who do this work, and maybe 100 get replaced each year. That makes the task of identifying and developing school leaders a manageable one, and it did become a priority in CPS.

There were efforts to create more aligned instructional systems: curricular materials, professional development, assessment data to judge the progress of students and feedback systems to support teachers in their own improvement. In the past, it had been the task of central administrations to make all these pieces run and work together because it’s so hard to put them together in individual schools. Not impossible, but hard.

That’s where some tension plays out. It’ll play out, for instance, around the new Skyline curriculum that CPS has heavily invested in. From what I know of the design principles behind Skyline [an online compendium of learning resources that the district spent $135 million to develop], it’s an attempt to create a coordination environment across various systems and generate good, formative information to support improvement. But that’s a huge undertaking, and it runs the risk of the central office defining what’s to be taught, how it’s to be taught and what evidence should be used.

The tension lies in the fact that you need lots of capacity to build an integrated instructional system that has the promise of actually delivering more ambitious academic outcomes, both reliably and at scale. But then you confront this political issue that democratic localism was intended to solve, i.e., “We want to push these problems into local school communities to decide what they think is best for their own children.” So to some extent, we’re shifting back now to more centralized control.

You’re describing these organizational dynamics and players in a very different way than I’m used to hearing about them, which is always through the prism of reformers vs. unions. Do you think that debates over K–12 politics are cast too simplistically, both by the press and the combatants themselves?

I do. When the second major reform act passed in 1995, it turned over control of the system to the mayor of Chicago, who appointed the board and the CEO. Since the mayor at that time [Richard M. Daley] also basically controlled the City Council, 49-1, you essentially had unitary politics in Chicago for a 15-year span. You just don’t see that in big, urban districts. And there was mostly peace between labor and management from 1995 to around 2011.

There were a few things that established that peace. One was that Illinois had swung Republican in 1994. We had a Republican governor and a Republican legislature, which had been very rare, and downstate Illinois was intent on taking a sledgehammer to the Chicago Teachers Union by stripping out a lot of provisions around collective bargaining. But when the mayor took over, his office chose not to use a lot of the power it had been given. They didn’t bludgeon the union; Paul Vallas actually figured out how to negotiate a multi-year contract with decent wages for CTU members. In the early 2000s, there was an element within the union that emphasized professionalizing teaching, and the system sent some resources in that direction as well.

At that time, there wasn’t a traditional labor-management conflict. In some regards, it looked more like a European system, where they’ve got more of a cooperative relationship than you tend to see in American cities. But it broke down after 2010, largely because enrollments were declining, and we had financial issues affecting both the city and the state. Those are what led to the closure of all those schools. The conflict is quite active again in Chicago, but there was a period of time when these forces were working together in a more productive fashion.

Those long-term declines in enrollment, combined with big deficits of academic and social-emotional skills following the pandemic, seem to pose the biggest problems to Chicago schools right now.

The situation is extraordinarily challenging. In big districts like Chicago, where revenues are predicated on a per-pupil basis, it’s all fine as long as the student margins are growing. But when you start subtracting, which is what the city has been doing for years, the fixed costs don’t go down with every person who walks out of the building. They closed a lot of schools, but they’ve still got a lot of schools that are already under-utilized and will probably become more so. The way we financially support school systems doesn’t really take that into account.

It’s going to be interesting to see a mayor coming out of the teachers’ union. With the move to an elected board, I would expect the teachers’ union to organize and have a significant voice within that new board. If you get this kind of progressive alignment — the union and the mayor and school board and the governor in Springfield — I’m curious to see whether these people can actually solve these challenges. It’s one thing to go around criticizing what others do, but they’ll now be in a position to do something. What would better look like, and how would they get to it?

Would you agree that, whatever the political configuration moving forward, the urgent question is whether the district can shrink its footprint to match the roughly 100,000 fewer students it now educates compared with 20 years ago?

From a purely financial point of view, CPS has got more buildings operating than it surely needs. But one of the results of that is that the typical school, particularly at the high school level, has gotten smaller. Of course, the smaller size allows more personalized relationships to form between faculty and students and parents. Going back to the ’90s, we did see that smaller schools were more likely to engage in reform in productive ways. You tended to see stronger reports about relational trust in that students felt that adults knew and cared about them more. No one intended this, but in shrinking the size and population of schools, they actually created resources for improvement by making them less bureaucratic places.

That certainly contributed to improved high school graduation outcomes: Reduced size has enabled more intimate relationships to form between adults and students which have, in turn, allowed more students to graduate. At the same time, you do have this financial squeeze that will almost certainly force the district to close more buildings.

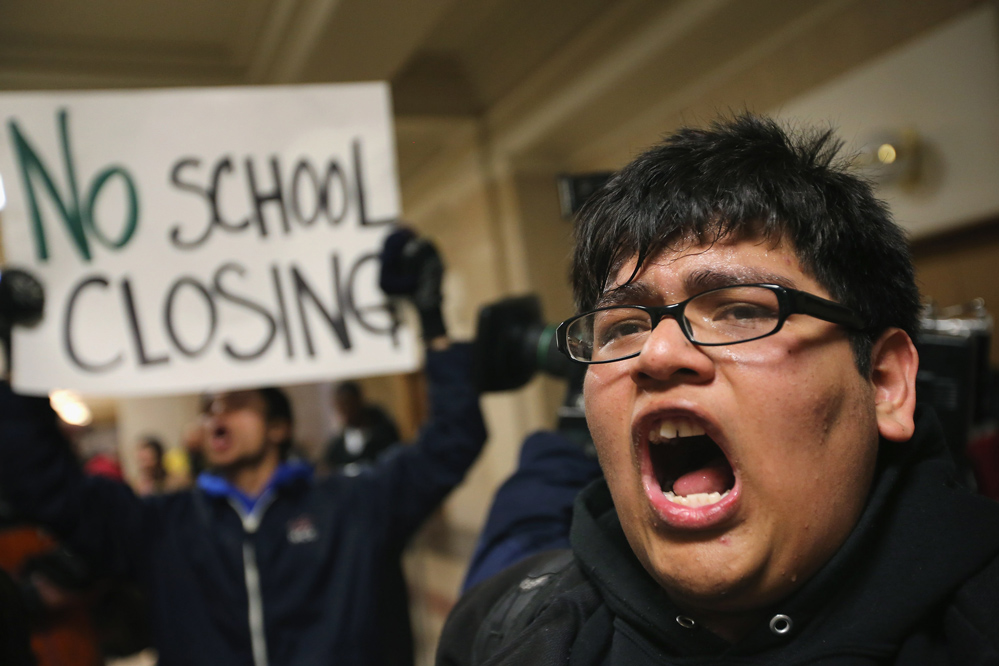

Do you think that’s feasible, given the backlash that school closures spawned during Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration? The shrinkage that you’re describing as almost inevitable is also a politically explosive scenario.

Without question, one of the most contentious issues in Chicago politics is that of closing schools. Emanuel closed 50 of them all at once, and there had been an initial threat of something like 130 candidates for closure. It fractured political alliances, and it was a key component of the revival of the Chicago Teachers Union as a political force.

If you go back to 1987, the union was broadly vilified across Chicago by parents and community leaders. In the opening pages of our book, we reproduce a very critical Chicago Tribune cartoon of the CPS from that era. If you fast forward to 2015 and the aftermath of the school closings, it was the union that organized parents and community members against the system. It was a fundamental realignment — but having said that, there was another shift of some dimension during the pandemic. The union was largely responsible for keeping Chicago schools closed for a very long time, which didn’t necessarily work to the benefit of all parents and children.

Another equally important factor is this period of racial reckoning. Race has always been a big issue in Chicago, but it’s gotten really heightened attention over these last four or five years. That has made it much more challenging to form the community relationships that supported improvement for several decades.

Is the CTU now the most important single actor in Chicago Public Schools?

In all likelihood, yes.

This is brand-new territory. Teachers’ unions have organized in other cities to get members elected to boards of education, but when a teachers’ union is recognized as being responsible for how a system operates, that’s really new. The elected board is structured to phase in over the next four years, such that half the seats are appointed — but they’re appointed by the mayor. In that sense, this is positioned to be as novel a governance reform as we saw in 1987, which was the most radical decentralization of public education that had ever been tried in the United States. Chicago is positioned to have a public school system run by its teachers’ union.

“This is positioned to be as novel a governance reform as we saw in 1987, which was the most radical decentralization of public education that had ever been tried in the United States. Chicago is positioned to have a public school system run by its teachers’ union.”

As an aside, something on the horizon that hasn’t gotten a lot of attention is the new authority for school principals to collectively bargain. Whether that actually comes into play is an open question, but if principals organize, it’s not clear to me that their union will be on the same side as the CTU on all issues.

At the same time, is it fair to say that some of the measurements of school performance in the district — including school ratings, which have relied to one degree or another on student test scores — are due to be refocused on different metrics?

I totally agree that these things are all being challenged. But they’re essentially written into regulations, and some of them are federally mandated by things like Title I and the Every Student Succeeds Act. While the existing assessments and their use will be challenged, they’re going to have to be replaced by something; I can’t imagine us going to nothing, no measures of achievement and school quality.

The question is, what are they going to replace it with? Over the last couple of decades, there’s been so much focus on being evidence-based in how researchers and policymakers do our work; but of course, that is predicated on evidence. So if you don’t like the evidence we’ve been using, what’s going to take its place? It might be hard to arrive at suitable replacements, especially in a heavily choice-based district like Chicago. In a choice district, parents have to have evidence to make their choices about where to send their kids to school — what are they going to use?

Again, that’s the difference between being in a critic’s role, where you challenge the status quo, and being in the governance role, where you say, “Here’s what we’re going to do instead.” Right now, it’s not clear that there is an “instead.”

If you were designing a district from scratch, would you create a school board of 21 elected members?

No, I’d have to say I would not.

Chicago Public Schools is something like a $9 billion operation. It’s a huge enterprise that has to be managed. A 21-member elected board managing a $9 billion enterprise — like I said earlier, this might be as radical a reform in governance as one could envision. There’s just no way to predict how it plays out.

“Would you want to be a superintendent accountable to a 21-member board? It just opens up challenges for which we have no precedent to suggest that it will work well.”

Could I imagine a scenario where this really works well? Yeah. I could imagine one where labor and management begin to come together because labor really has a stake in the success of the system. In the old days, they might have said, “Well, that’s management’s responsibility, not ours.” Now it’s all “ours.” So yes, this could evolve in a productive fashion. But would you want to be a superintendent accountable to a 21-member board? It just opens up challenges for which we have no precedent to suggest that it will work well.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)