New Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson Inherits America’s Worst Teacher Pension Mess

Aldeman: It's a big claim, but the Windy City's teacher retirement plan is arguably the worst in the country. Here are the numbers that back it up

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As the newly elected mayor of Chicago, Brandon Johnson just inherited what is arguably the worst teacher retirement plan in the country.

That’s a big claim, so let’s walk through some numbers.

First up is the cost side. Next year, Chicago will contribute more than $1 billion toward the city’s teacher pension plan. A large portion of that money will come from the state, and another $550 million will come from a dedicated property tax levy the state authorized in 2018.

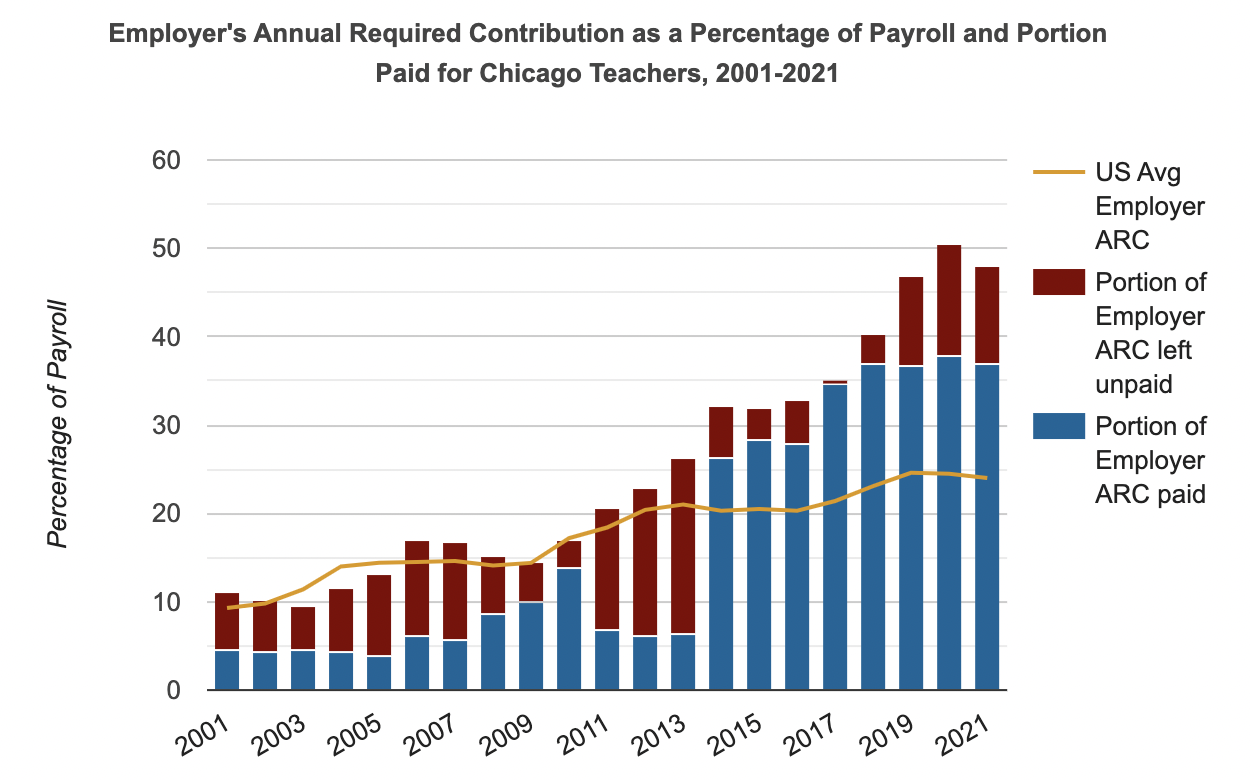

And yet, all this money is not enough. The chart below comes from the Public Plans Database from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. As the chart shows, Chicago’s pension contributions have risen substantially over time (the blue bars), but not once in the last 20 years has it contributed as much as what its actuaries recommended (the red bars). In 2021 alone, that gap amounted to about $350 million.

These gaps have added up over time. The result is that the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund is in worse financial health than it was a decade ago, despite the ramp-up in contributions and a very strong decade of investment returns.

A few statewide teacher pension plans — notably the rest of Illinois, Kentucky and Connecticut — are in similarly dire financial straits. But Chicago is different because it’s a city. It’s dependent on city taxpayers to fill any budget gaps.

There are a few other cities that, like Chicago, offer their own teacher pension plans rather than participating in a statewide system. New York City, Kansas City and St. Louis are notable examples, with challenges similar to Chicago’s. What brings Chicago to the bottom of the heap is on the benefits side.

Facing their own state pension problems, in 2010, Illinois legislators created what’s called Tier 2. Its new rules applied to Chicago as well as state employees. The state raised the age at which new employees could retire from 55 or 60 to 67, added a new cap on the maximum benefit an employee could earn and reduced cost-of-living adjustments for retirees.

The new Tier 2 also imposed a longer vesting period for new workers: Employees hired on or after Jan. 1, 2011 would need to serve for at least 10 years before qualifying for any retirement benefits at all.

How many Chicago Public School employees make it to 10 years of service with the district? Not many. The pension plan conducts regular “experience” studies based on its own data, and it estimates that 30% of new employees will leave the district in the first year and less than 1 in 3 will make it 10 years.

In other words, the majority of Chicago employees in Tier 2 won’t qualify for any pension from the system.

Of course, some long-term employees will still qualify. But on average, the city estimates it’s not spending any money at all on Tier 2 member benefits.

This may sound incredible, given the cost figures cited above, but it’s all spelled out on page 23 of the pension fund’s latest actuarial report. For Tier 2 members, the total “normal cost” of benefits is 8.99% of salary. But each member contributes 9%. In other words, Tier 2 members are putting in more toward their benefits than they’ll get back. They’re getting negative 0.1% in retirement benefits.

Oh, and Chicago teachers are part of the 40% of educators nationwide who also don’t get Social Security. Someone could teach for nine years in Chicago and have no retirement benefit at all, outside of any personal savings.

This would be illegal in the private sector, where federal law requires that employees qualify for retirement benefits after no more than five years. There’s no such protection for public-sector workers. Similarly, Congress attempted to guarantee minimum benefits for public-sector employees without Social Security coverage, but a loophole allows Chicago to offer these meager benefits to workers without any consequences.

I don’t envy Mayor-elect Johnson. The latest actuarial valuation report also notes that contributions would need to increase if the city’s payroll declines as student enrollments continue to fall. These are not problems of Johnson’s making, and they can’t be easily solved from the mayor’s office. But they are now his problems to deal with.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)