74 Interview: Pulling All the Levers — Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson on Getting More Students to and Through College

See previous 74 interviews: Presidential candidate Cory Booker talks about the success of Newark’s school reforms, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Co-CEO Priscilla Chan on supporting the “whole child,” then-Rep. and now–Colorado Gov. Jared Polis on school funding and special education. See the full archive here.

The sigh of relief that ricocheted through Chicago Public Schools (CPS) last month was audible beyond district boundaries. New mayor Lori Lightfoot announced she would retain CEO Janice Jackson, whose 18-month tenure had earned her widespread support. Her December 2017 appointment came on the heels of years of brutal battles over school closures, sex abuse allegations, and bitter budgetary and teacher contract disputes.

Having spent both her childhood and her career in CPS, Jackson is the first district teacher to be elevated to the top job since 1995; her history gave her the relationships and the credibility to build on ongoing efforts that were just beginning to attract national notice for pushing up graduation rates and college attainment. Key among them was a partnership in which University of Chicago researchers analyzed district data and made specific — sometimes basic — recommendations, such as identifying ninth-graders at risk of dropping out.

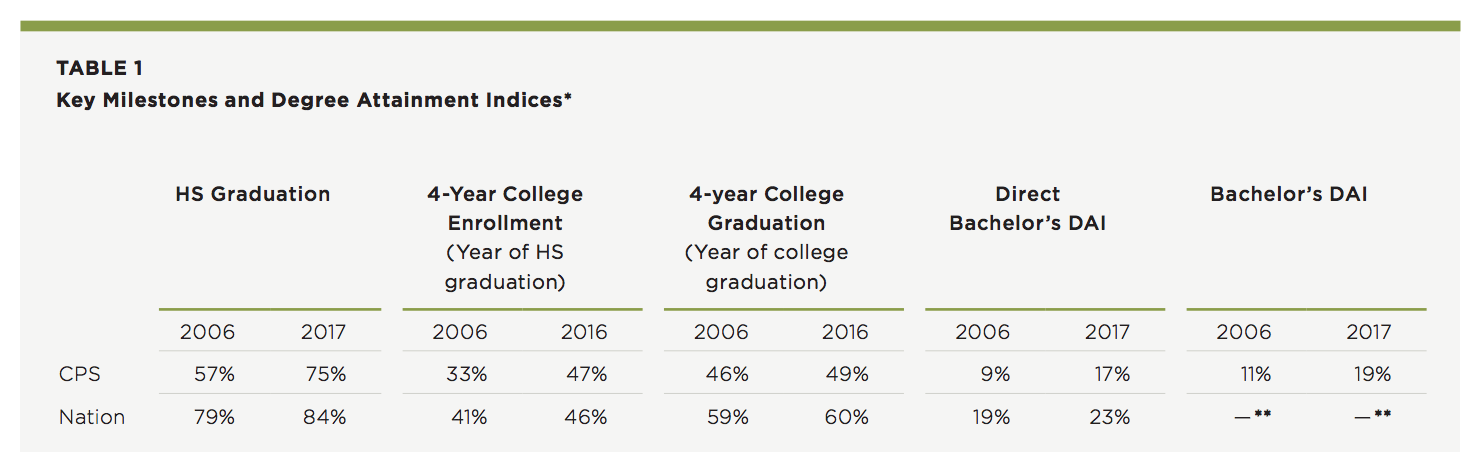

CPS also boosted the number of students taking challenging Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes, enrolling in dual-credit classes for no charge at the City Colleges of Chicago and earning career-readiness credentials while still in high school. The combined result: The graduation rate rose from 57 percent in 2011 to 78 percent last year, a 37 percent increase. The increase among students of color was twice as fast as the national rate between 2013 and 2017.

A record 89 percent of high school freshmen were on track to graduate last year. Starting in 2017, one graduation requirement is that students complete a concrete plan for life after high school, encompassing not just college but also more direct paths to a good job.

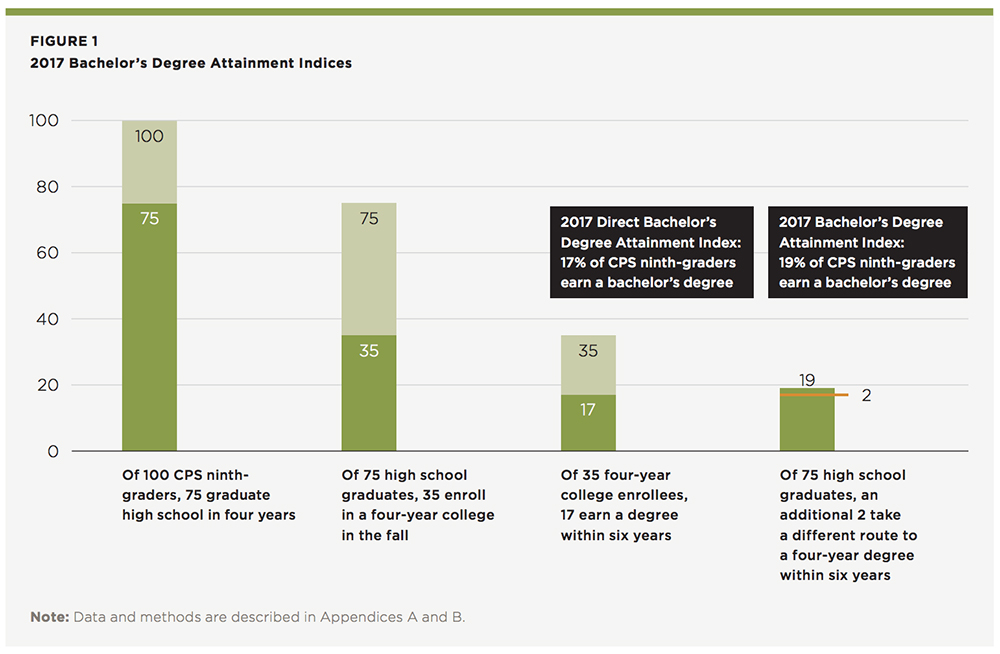

CPS is closing in on a goal of ensuring that half of graduates have college credit or a career credential at graduation, and it has boosted immediate enrollment in a two- or four-year college among graduates from 50 percent in 2006 to 65 percent in 2017. The number who earn bachelor’s degrees remains small but has doubled in that time.

CPS Commitment to Postsecondary Success (Text)

Good news notwithstanding, as head of the nation’s third-largest — and possibly most politically cutthroat — district, Jackson is on a path that still leads straight uphill. She took time off recently to talk to The 74 about the hydra-headed effort to send more students to college — and make sure they are equipped to earn a degree. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: Is it true your relationship with Chicago Public Schools began in preschool? You must have learned firsthand how a student did or didn’t become college-bound and what that trajectory looked like.

Jackson: I’ve been in Chicago my entire life. I was educated in the CPS school system and Public Illinois University systems, from Head Start through college and beyond. I’ve had an opportunity for my entire life to experience public education, its current state and desired state. A lot of the policies and things that we will talk about speak to my experience as a student, but also as an educator in this district.

I went to a high school that had a selective program; students were selected based on test scores. I don’t know this to be a fact, but I’m pretty sure we had the best teachers because I had some amazing teachers who poured [learning] into me over time.

I didn’t reflect on this until after I became an educator at CPS, but junior year I was in study hall. A counseling assistant came in and passed out letters — invitations for us to come and take the ACT on a Saturday. I remember being surprised. Some of my classmates were not invited. If I’m being honest, I was mad. I’m like, “Why do I have to come? It’s on a Saturday. I want to sleep in.”

My mom graduated from high school and spent just the first year in college. My father did not complete eighth grade. But they both valued and pushed education on us from day one. Even if I didn’t want to go, that envelope was going home and we were going to have a discussion about it.

I’m the middle child of five siblings. My older brother and sister are college graduates. When I went home and we talked about it, they knew exactly what it meant and explained that you can’t go to college unless you take the ACT. Which is something I didn’t know. Something we didn’t talk about in school.

That story highlights the place that we’ve come from. Where someone looking at student performance — I’m not sure what they were looking at — decided who was college-bound and who wasn’t. From a time where you can be an honor student with a desire and aspiration to go to college, which I had, and not have a clue how to do that. It speaks to a lot of the changes we made that seek to ensure that every single student has what they need in order to pursue college, should they choose to.

Kids in CPS now don’t have to figure it out the way we had to figure it out. Today every student in CPS has to take the SAT in order to graduate. They don’t have to get a certain score, but every student does that in order to graduate.

We recently created Learn, Plan, Succeed, an initiative we’re very proud of which says that every student will have a concrete postsecondary plan upon graduation. Which could include college, but also other postsecondary pathways that we hadn’t paid as much attention to in recent years.

We have gone from a place where students were selected to a place where the requirements are for everybody. What we’ve seen as a result of that is steady increases in SAT scores. We’ve seen steady increases in students matriculating into college. We seen a pretty substantial increase in college completion.

The UChicago Consortium for School Research published a study last year showing that 9 percent of CPS 2006 graduates earned a college degree by the time they were 25, which was much lower than the national average, which at the time was 23 percent. (The 9 percent figure refers to the percentage of graduates who proceed directly from high school to college, where they earn a degree within six years. The current overall college graduation rate of CPS graduates is 49 percent.) We’ve been able to double that rate and counting in the past eight years. We started at a real disadvantage. The only way we were able to do that is because we’ve been working to have more minority and low-income students take on college as an option.

Our numbers with regard to selective enrollment, kids in our top schools that have to test to get in, those numbers are pretty consistent. We’ve seen dramatic growth in students in our nonselective schools, which is something that we’re really proud of.

Is any of this an outgrowth of your experience first as a teacher and then as a principal in the system? How did those experiences inform your practice?

I can tell you a lot of stories about that. One I share often, which I think gets back to the two-tiered system: My initial goal was to be a college professor. Which is something that I still would love to do one day, but also it’s odd — I don’t think there are many girls from the south side of Chicago who want to go to college to study history and teach it.

My plan was to teach for a little while, while I earned my master’s degree and doctorate degree, and then I would teach at the collegiate level. I ended up getting a job straight out of college, which was nice. That’s when it really hit me that the same system that I was criticizing while I was a student, I had directly benefited from. I was in that group of people that had been privileged.

Despite my profile, being from the south side, growing up in the system, that was something that wasn’t apparent to me. I didn’t realize that me and my siblings had a different experience because our parents were so involved in our education and that we were afforded opportunity that other people didn’t even know existed.

I remember working at this school, South Shore High School, which at the time was one of the lowest-performing schools in the state. I don’t say that to be dramatic. It was a fact. Because of that, a few things happened. Number one, we were subjected to — exposed to, responsible to implement — every single reform initiative that people dreamed up. A lot of my colleagues, they of course resisted that.

At that time, there were so many opportunities where senior leaders, funders and all sorts of people were in and out of the building. At one point there was a call to action around creating the small schools that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was supporting. Based on some success in New York, they believe that in order to improve large, comprehensive high schools, you had to break them up into smaller units.

I decided after only teaching for two or three years that me and a group of teachers were going to start our own school because I had become frustrated with what I had seen. I was an OK teacher — I didn’t get a lot of support — but I think I was a great principal. We ended up opening a new high school.

I had experienced something completely different, and the majority of the kids in CPS, especially the ones that looked like me, did not have that experience. Something turned on in me at that time. I wanted to create a school where that was happening consistently in every classroom across the board for kids.

I decided to change career paths. I applied for a leadership program because I wanted to be the principal of the school that we were starting. I also wanted to be the CEO of Chicago Public Schools. I was only 24 years old. I said I’m going to be the CEO by the time I turn 40 — and that’s exactly what happened.

Now, I didn’t believe that was going to happen. I wrote it so that they would pay attention to my application. My professor, who’s one of my mentors today, reminds me that he did think I was a little wild for saying that.

But you also have to think about the time and space that we were in. Especially here in CPS, where conventional logic had changed to “Educators should not be running the district” — that you needed people with strong business acumen to come in and turn around a huge bureaucracy with a multibillion-dollar budget. They had plenty of examples to point to in the past where it hadn’t worked out.

I’m happy to say there’s been a shift. If you look at a lot of the large urban school districts in particular, you see more people who are actually educators leading them, which is something that’s positive to me. That was not the case and that was not the path that a lot of school systems followed in the past 20 years of school reform.

When we talk about reform, so often we talk about silver bullets. But what CPS did was to pull a dozen or more levers in concert, intentionally or not. Can you talk a little bit about how many moving parts your increased success rate has required?

What you pointed out is exactly how I would characterize our work, that we are using a lot of different levers. We also, in my opinion, have a very practical approach, which sometimes bumps up against the media or policymakers wanting us to push back even harder. There’s pressure to have a silver bullet.

What CPS has done is we’ve made sustained incremental progress over time. When you look at the total result, you see something that’s pretty remarkable in a large public education system. That approach is how we think about the work.

I would call out a few things that I think have really helped us get to this level. First is a reliance on data. Our partnership with the Consortium on School Research [and its To&Through Project] is extremely powerful. Sometimes when I talk to other superintendents, they wonder about CPS having a relationship where a third party has access to all of our raw data. But this partnership has resulted in them being able to identify things that were not as apparent to us because we’re in the busy day-to-day work.

One example would be the college attainment report that I talked about earlier. They did a longitudinal study and tracked CPS students’ performance over time. That led to, first of all, awareness around how dismal our college completion rate was, but also allowed us to set goals and come up with strategies around how we would move that rate.

We looked at district policy levers, but also things that we could do at the local level through empowering our principals and postsecondary leadership team and the teaching teams more broadly. I would say every initiative that we rolled out, we think about it from those various levels. If we don’t have a way for principals and teachers to access the work, or the strategy we’re trying to implement, we know that strategy is dead in the water.

We try to think about what’s the lever that we can use at the district level? But we spend much more time looking at what is it that principals and teachers need? How will they access this? How will this empower them? How will this change practice so they can do their best work?

I want to offer you the chance to pose and answer your own question.

When we first launched Learn, Plan, Succeed, the initiative around the postsecondary aspiration, I remember being asked by a reporter, “Do you think that you are pushing middle-class values on students?” That was the question.

I didn’t really understand what she was driving at specifically with that, but I was able to infer. What I explained to her is that’s one way to look at it, but, if by middle-class values you mean ensuring that every single student has what he or she needs in their back pocket at their disposal so they can make an informed and educated choice about what they’re going to do with the rest of their life — if that means middle-class values, that’s exactly what we’re doing.

The type of things that happened in my family, a working-class family, the value around education, the relentless pursuit and ensuring that you had a plan — if that’s what we’re accused of trying to do for every kid here in Chicago, then I accept that accusation, because that’s exactly what we’re trying to do.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)